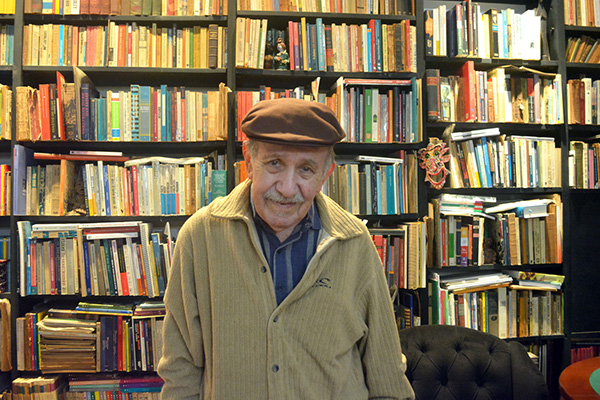

Paul Singer is one the most distinguished intellectuals of the Solidarity Economy in Brazil and in the world. His publications include: Desenvolvimento e Crise [Development and Crisis] (1968), Desenvolvimento Econômico e Evolução Urbana [Economic Development and Urban Evolution] (1969), Dinâmica Populacional e Desenvolvimento [Population Dynamics and Development] (1970), Dominação e desigualdade: estrutura de classes e repartição de renda no Brasil [Domination and Inequality: Class Structure and the Distribution of Income in Brazil] (1981) and Introdução à Economia Solidária [Introduction to the Solidarity Economy] (2002). He was born in Vienna, Austria, and moved to Brazil in 1940. In 1953, at the age of 21, Singer was a militant of São Paulo’s Steelworkers Union and a leader of a historical strike that lasted for over a month. In the 1960s he merged his militant and intellectual activities, starting his career as professor of Sociology and Economics at the University of São Paulo, also studying Demography at Princeton University. At the end of that decade his political rights were revoked by the military dictatorship and he helped found the well-known think tank Centro Brasileiro de Análise e Planejamento (CEBRAP). After his return to teaching, Singer helped launch the Worker’s Party (PT) and then became São Paulo’s Municipal Secretary of Planning and later the National Secretary of Solidarity Economy. Here he describes his experiences with the Solidarity Economy and how such initiatives can contribute to a more equal world. Paul Singer is interviewed by Gustavo Taniguti, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of São Paulo and Renan Dias de Oliveira, a professor at the Fundação Santo André, Brazil.

GT&RO: In 1969, together with Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Octávio Ianni, José Arthur Giannotti, Juarez Brandão Lopes and Francisco de Oliveira, you founded the Centro Brasileiro Análise e Planejamento (CEBRAP). It was a group of intellectuals who had a critical perspective during the most repressive years of the military regime. What was the importance of this initiative to discuss poverty in Brazil?

PS: We did research on poverty at that time because we realized that it was the country’s real big problem, but we did not know the other side of the coin – prosperity, wealth, or whatever you want to call it. So we were not able to measure inequality as we can today, we did not have access to all the information we needed. At that time, I would say that the main social problem in Brazil ‒ at least for us at CEBRAP ‒ was exclusion. And exclusion is almost always the result of poverty.

GT&RO: After almost ten years of political persecution, in 1979 you returned to academic activities after the military regime forced you into mandatory retirement; and in 1980 you participated in launching the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party). At that time, what prompted the discussion of the Solidarity Economy and cooperatives? How did you engage this issue?

PS: Nobody at CEBRAP actually had contact with Solidarity Economy at that time, I think it was an unknown issue. Much later, I found out that Solidarity Economy was inspired by the Catholic Church. The term Solidarity Economy was created by a Chilean economist, Luiz Razeto. He wrote several books about it. He is now retired, but still writes on this subject frequently. The founding of the Workers’ Party in 1980, soon after the 1979 amnesty, was not connected to the debate on Solidarity Economy. My interest in the subject came from an individual initiative. Like many other people, I was deeply impressed by the sudden disappearance of the so-called “real socialism.” Very quickly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, political regimes from many countries collapsed one after the other. Within the Workers’ Party, the fall of so-called “real socialism” provoked an ideological crisis. It was a big challenge for us, as we were a socialist party who wanted to build a different society in Brazil. I spent a lot of time and energy to bring about something we called “democratic socialism.”

In the 1990s Brazil faced a tremendous crisis, which particularly affected the country’s employment system: 60 million jobs simply disappeared during that crisis. I felt deeply concerned about it because before then, Brazil had never experienced an unemployment rate like that. Then, suddenly, millions of industrial workers were losing their jobs, houses, and incomes. It was a real social tragedy, and because of that I was invited by the Church to visit some of the cooperatives that were being created in Brazil at that time. Caritas, which can be considered as the social arm of the Catholic Church, created over 1,000 workers’ cooperatives, mainly made up of unemployed people. And visiting many of these cooperatives I discovered the answer to the hard question of what social democracy meant. Because those cooperatives were founded by the unemployed, they had no bosses, no hierarchies. Everything was made in a collective way, equally. I wrote a few articles at Folha de S.Paulo newspaper, including one called “Solidarity Economy: A Weapon Against Unemployment.” I was not creating a new movement. Actually, I was only discovering it.

GT&RO: Still in that context, what were your theoretical orientations in the debate on Solidarity Economy?

PS: I would say that the main reference point was the history of socialism, beginning with the utopian socialists. It is curious because I used to read a lot of Marx, Rosa Luxemburg and other Marxist authors, but not the utopian socialists. In one of my classes in a university here in São Paulo, when students asked me to tell them more about those authors, I began to read Robert Owen’s work. I thought it was admirable and I adopted it as a point of reference.

GT&RO: When you became São Paulo’s Secretary of Planning, during Mayor LuizaErundina’s tenure (1989-1993), were the city’s anti-poverty policies related to Solidarity Economy? If so, how?

PS: Initially no, but it developed later. São Paulo is the largest city in Latin America, an enormous sprawling and unequal metropolis, and that government was the first left-wing one to rule the city, the first one with a woman as mayor. More than that, Luiza Erundina came from a poor family from a state in northeastern Brazil, Paraíba. She joined the Workers’ Party and became a leader very quickly. Of course, in her government, poverty was our main target since we had to overcome the 1980s crisis. I remember that the mayor, the workers’ unions and myself debated how to reduce unemployment rates. Later Lula said to me that the unions could not support the unemployed, because they did not know what to do with them. In his view, the unions could only support active members of cooperatives. It was very objective. The employers in their turn offered help in exchange for tax reduction, which was impossible because it would have affected the budget of basic services, such as education and health.

So it was a very difficult context. First we created a task force to carry out the first census of homeless people in order just to save them from starving! Later we created recyclable material waste-picker’s cooperatives. This was the beginning of the Solidarity Economy. Particularly with help from Caritas we found out what Solidarity Economy was all about. We decided to adopt 100 percent of the principles of cooperativism, and by 1996 I was convinced that it was an expression of democratic socialism.

GT&RO: In the 2000s, two important spaces to debate and plan the Solidarity Economy were created: the Fórum Brasileiro de Economia Solidária (Brazilian Solidarity Economy Forum) and the Secretaria Nacional de Economia Solidária (Solidarity Economy National Secretariat, an organ from the Ministry of Labor and Employment). Could you tell us about the political context in which they were created? How do they assist Solidarity Economy at the national, state, and municipal levels?

PS: It was a context of high unemployment rates, though not as severe as those we had had in the 1980s. Cardoso’s government was strongly neoliberal in many ways. The most important thing for him was the fight against inflation, which he did by increasing interest rates, resulting in unemployment – which leaves workers with little bargaining power.

When Lula was elected in 2002, he was already sure that the Solidarity Economy would be included in his government program. The Workers’ Party adopted the Solidarity Economy, and it is still included in the party platform. As Lula began his term as President, the Solidarity Economy movements started to hold national meetings, pushing for the creation of a secretariat at the Ministry of Labor and Employment. This happened very quickly, in 2003, after Lula took office. We spent some months getting the approval from Parliament, but in June of that year the Solidarity Economy National Secretariat was finally created. The Brazilian Solidarity Economy Forum was linked to the Secretariat because logically we would not introduce any policy without social movements. It would not make any sense. With the Forum, all policies result from an interaction with social movements, which provide live reports of the Solidarity Economy’s problems, claims, and demands.

Today, Solidarity Economy crosses the whole country, from the Amazon to the South. It is not as big as we would like, but it is not a small movement anymore. Besides the Secretariat, the same law created a National Council, most of whose participants come from the Forum.

The Secretariat uses its budget to promote and assist Solidarity Economy cooperatives. We did this especially during Rousseff’s first term, participating in the Brasil sem Miséria program. Five or six ministries were part of that program; the Secretariat was responsible for productive inclusion in urban areas, bringing opportunities to create cooperatives to whoever might be interested. Our estimate is that this policy helped bring around half million families out of poverty. But we were not the first country to have an official institutional support for Solidarity Economy. France was first. In 2001, at the First Social Forum, we met the French Minister of Solidarity Economy.

GT&RO: Could you explain how the university-based incubators started?

PS: Incubators were started originally in the United States. They are important to the extent that they stimulate students and professors to create enterprises in the university environment. And they work very well. The Federal University of Rio de Janeiro had the first incubator for the Solidarity Economy in 1994. Our incubators are different in that they are not devoted to science, but are mainly interested in social issues. After a few years we saw popular cooperatives being reproduced in Rio’s shantytowns, and now in Brazil many public universities have their own incubators, supported by the Secretariat. At present we have 110 incubators in Brazilian universities. These popular incubators also have a big impact on universities because the students who work there come from different areas: economics, geography, social sciences, and engineering. But they are mostly middle-class students who have contact with and are finding ways to assist the poorest communities for the first time in their lives. It has a positive impact on the campus.

GT&RO: In your view, what are the virtues of economic organization ruled by workers’ associations? And what are the challenges faced by the Solidarity Economy in Brazil today?

PS: I would say that the biggest virtue is democracy. People work together, respecting each other, without competition. Our Solidarity Economy map shows that in Brazil we have about 30.000 active cooperatives, involving around three million people. And we have support from important parts of society, such as the Catholic Church, the Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT), and the universities. It is a very new and stimulating social experience.

Among the challenges to the Solidarity Economy in Brazil, the most important one is that the Solidarity Economy enterprises are somewhat fragile. Many of them disappear in five years. Generally, small enterprises have a short life. But, of course, not all of them are small. For example, we have the Fábricas Recuperadas (Recovered Factories), when a bankrupted factory is recreated and replaced by a cooperative. In Brazil we have 67 Fábricas Recuperadas and in Argentina you will find many more.

GT&RO: How do you see the Solidarity Economy in Brazil compared to other experiences in Latin America and around the globe?

PS: I am still learning more about Solidarity Economy almost every day. At the local level, dealing with the fragility of enterprises is a big challenge, and the cultural element is also very important. Internal conflicts and disagreements between groups can be decisive in the success or failure of an enterprise. We must know how to avoid conflicts – and more than that, how to solve them. I am not sure how central the cultural factor is for the Solidarity Economy around the globe, but surely a comparison with other countries such as South Africa, Philippines, South Korea ‒ and many others from Europe and Latin America ‒ would be important to building a democratic work environment. We must learn from them.

Gustavo Taniguti <gustavotaniguti@gmail.com>