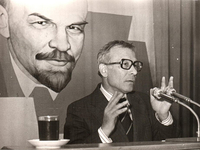

The first time I met Vladimir Alexandrovich Yadov was during the department meeting at the Philosophy Faculty of the Leningrad State University, where I worked as a stenographer at the same time as being a student. As I recall it was at the beginning of 1965. Vladimir Yadov had just returned from his academic training in England and was giving a presentation to the faculty. This presentation was so informal and entertaining that, accustomed to monotonous incomprehensible talks of our philosophers, I became an immediate convert to sociology. I applied and was admitted to the Philosophy Faculty, hoping that eventually it would lead to specialization in sociology. At that time Historical Materialism reigned in the discipline.

Although I was O.I. Skaratan’s graduate student, Yadov became a mentor, close colleague, a friend, and an example to follow. Later, he would become an excellent boss, very easy to work with.

Truly, he was a sociologist blessed by God. He was a public sociologist who easily communicated with any human being – no matter whether a high-rank official, even a President, or an ordinary person from our surveys. He was never arrogant, always sticking together with his colleagues during conferences and informal parties. As his contribution to collective labor, he would regularly visit the state farm, Lensovetovski, where he would weed and pick cauliflower and turnips – something our other administrators rarely did. The female farmers adored Yadov, expectantly awaiting his arrival. The brigadier would warmly lecture him: “Hey, Professor, why are you picking vegetables of only one type? You need to sort out the turnips that are for the people from those that go to feed livestock.” Yadov would instantly reply with a joke, and proceed to raise questions about the working conditions, lives and families of the farmers.

Together we went through the hardest and murkiest times. But he managed to keep his chin up. He betrayed no one, while helping many. Indeed, it could be said that he saved people. I received his support in very difficult times in my life. It was he who suggested that I take up the position of Party Secretary in our sociology department in order to keep an eye on things and defend ourselves against attacks. After all, the Communist Party was the most common public space for polemics and debates about sociology.

At the same time we never stopped doing research, conducting surveys, but we also loved reading detective stories. Yadov was devoted to this genre because, so he believed, these stories developed the intellect, logical thinking, and provided knowledge of day-to-day life as well. After Yadov was fired from his job, either he or Ludmila Nikolaevna (his wife) would call me inquiring about new detective stories. At that time my women friends kept private book collections, containing unauthorized translations of detective stories and novels of famous foreign writers. They also had friends and relatives abroad, who would smuggle books into Russia. Then, those, like me, who were fast typists made copies on a typewriter. I still have copies of samizdat detective novels.

Yadov’s favorite song was “We were buried somewhere around Narva” by Alexander Galitch. We sang that song at almost every party where there was a guitar or an enthusiastic gathering. Yadov always emphasized certain lines of the song: If Russia is calling for her dead sons it means it is in trouble However, we see that it was a mistake – and what a waste In the fields where our battalion was slaughtered in 1943 for nothing Today the hunting party enjoys the killing and huntsmen blow their horns.

Once I asked him why he liked that particular song and he replied that it was because the song was about victims of meaningless sacrifices made for the sake of a common goal – something that took place throughout Russian history, no matter whether it was during times of war or peace.

I remember at the 50-year anniversary celebration of the Institute of Socio-Economic Research, we presented him with a barrel of wine. He was very happy and asked to be sent home sitting on the barrel. “Imagine,” he said, “Ljuka [his wife’s name] opens the door and there I am, sitting right in front of her on the barrel with no one around.” That was Yadov.

I also remember him bringing water-resistant pants from Budapest for my six-month-old son. They turned out to be too small. He complained: “You feed your boy too much.” Nonetheless, he managed to exchange the pants for the right size’s ones through his friends. That was Yadov – very human, close, understanding, and very intelligent. At times his way of thinking was incomprehensible – capable of binding together weird things.

My last and very personal memory is about Yadov two years ago. Oleg Bozkov and myself were visiting him at his home in Estonia. Alexei Semenov, one of Yadov’s favorite students and a long-time resident in Estonia drove us there. At that time Semenov was planning to run for a seat in Tallinn’s legislature. He and his wife Larisa provided the most tender care for Yadov. Frankly speaking, those were one of the happiest and most cheerful times in my life. We were browsing through our memories, telling jokes, drinking martini and red wine. We also discussed the role and place of sociology today, what sociologists should do and how they should respond to the challenges of present times, especially when strangled by the authorities. We will all remember him for his humanity, his inexhaustible interest in life and for his totally unexpected conjectures, inferences, and subjects for research.

Tatyana Protasenko, Institute of Sociology, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia <tzprot@mail.ru>