South Africa’s Violent Democracy: An Interview with Karl von Holdt

February 13, 2016

Karl von Holdt has had a long and distinguished history of political engagement and scholarship. He was editor of the South African Labor Bulletin, at a time when labor was dictating the movement of South African society. He has worked for NALEDI, the policy institute of COSATU (Congress of South African Trade Unions), and served as coordinator of COSATU’s Commission on the Future of Trade Unions (1996-7). Most recently he served as labor’s representative on the National Planning Commission of South Africa. He is now Director of the Society, Work and Development Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. His many publications include Transition From Below: Forging Trade Unionism and Workplace Change in South Africa, one of the most important analyses of South Africa’s transition to democracy. With Michael Burawoy he co-authored Conversations with Bourdieu: The Johannesburg Moment (2012). His current research includes the functioning of state institutions, collective violence and associational life, violent democracy, citizenship and civil society. Von Holdt is a member of ISA Research Committee on Labour Movements (RC44). He is interviewed by Alf Gunvald Nilsen of the University of Bergen. A longer version of this interview can be found in Norwegian in the newsletter of the Norwegian Sociological Association.

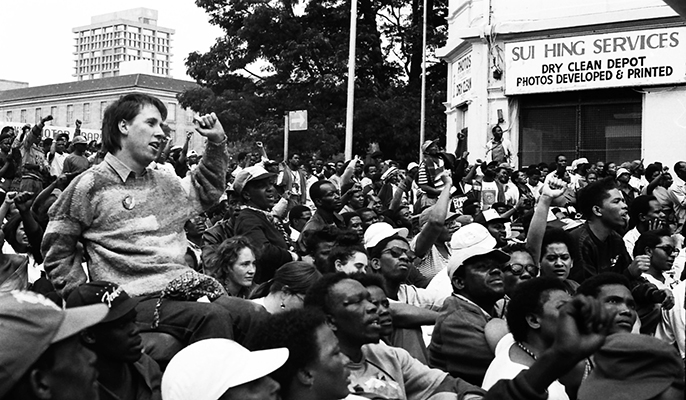

When South Africa emerged from apartheid to democracy in 1994, decades of popular struggle seemed to have yielded a resounding victory, brimming with hope. “Out of the experience of an extraordinary human disaster that lasted too long,” newly-elected President Nelson Mandela announced, “must be born a society of which all humanity must be proud.” Some twenty years on, social realities in South Africa complicate the picture: despite new political freedoms, entrenched racialized inequality and poverty persist. In the “rainbow nation,” discontent fostered by enduring inequalities has resulted in a series of xenophobic attacks on migrants from other African countries. How does a sociologist make sense of this complex and contradictory scenario?

South Africa’s Violent Democracy

“There’s a lot that is paradoxical and perplexing,” says Karl von Holdt, Associate Professor and Director of the Society, Work and Development Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand. Von Holdt speaks not only as a sociologist, but also as someone who has moved between activism and academia since the early 1980s.

Von Holdt acknowledges the significance of apartheid’s fall. “The kind of world we lived in – the racial domination, the oppression, the daily institutionalized brutality of the system, and the denial of rights – the weight of that has gone.” At the same time, an underlying and seemingly intractable structure of exclusion persists. According to von Holdt, however, it would be wrong to suggest that little has changed. Rather, the changes unfolding in South Africa today defy easy conceptualization. “Both politically and sociologically, there’s a tyranny of certain conceptions of how the state should work and how social orders should be organized, which originates in the crucible of western modernity. When we look at ourselves through these concepts, it’s easy to conclude that we don’t have democracy because our society is so violent, leading to despair at our shortcomings. However, I believe that we have to look at things differently – both in terms of how those concepts originate in Western history, and in terms of how they are deployed in the South African context.”

This attempt to look at things differently leads von Holdt to describe South Africa as a violent democracy. Violence and democracy are not mutually exclusive, he notes – a claim that is as true of European state formation as it is of contemporary South Africa. “In a European context, it is easy to think of modernity as a centuries-long process of pacifying populations and establishing peaceful ways of managing conflict. But if we think in more global terms, it becomes evident that these processes were all coeval with colonial conquest and domination, which were integral to European development. In South Africa, our historical experience of modernity is of an exceedingly violent process; we’ve experienced violence for four centuries!”

For von Holdt, today’s violence is closely linked to the important changes unfolding in South Africa – especially, the formation of black elites, played out through struggles on the terrain of the state. South Africa’s political settlement, he notes, “enshrined both socioeconomic and human rights. But it also protected property rights. Now, the distribution of property rights in South Africa has been shaped by 360 years of colonial dispossession and apartheid and is consequently grossly racialized.” Because the constitution limits prospects for systematic redistribution, the state’s role in the country’s economy assumes great significance. “The state is by far the biggest employer in South Africa and also has substantial budgets for contracts of various kinds. Huge resources are locked up in these processes, and accessing those resources becomes crucial for elite formation,” he argues. “To get into power and to remain in power, you need supporters, allies and networks of patronage. Having access to wealth and resources that can be distributed at all these levels is a way to build political capital. Conversely, to be successful as an entrepreneur, you need political connections. In this way, wealth and politics are closely bound up with each other.” Power struggles assume an increasingly violent character as different factions and rivals try to immobilize each other: “That’s where the battles are, and they are vicious.”

South Africa’s violent democracy is also marked by protests in poor communities. Such protests – often related to discontent over the delivery of public services – are often described as an autonomous expression of resistance by the poor, but von Holdt argues that protests also arise from “the dynamic of elite formation, generated by organizing patronage, accessing resources, and forming factional ties into networks among the poor.” As von Holdt and a team of researchers investigated community protests in Mpumalanga and Gauteng provinces, he says, “we realized that there was an intimate relation between leading figures in the protests and political networks within the ANC. The people leading the protests were often part of a particular faction of the local ANC, who aimed to gain power within the local ANC branch and the local council.” However, von Holdt does not suggest that poor people are simply manipulated by local political elites. “There are real grievances within the community. If local political leaders want to become elites, they have to tap into the discontent of the poor. And in this way, poor people also use leaders to gain voice and to access scarce resources. So patronage is not simply something that is dispensed by elites; it is also something that the poor lay claim to.”

Still, changes in the South African political landscape may prove significant – including changes dating from 16 August, 2012, when police forces killed 34 striking mineworkers at Marikana. Emblematic of South Africa’s violent democracy, the Marikana massacre also set off organizational ruptures, weakening the ANC’s hold over the country’s trade unions. In late 2014, the United Front, a broad coalition of progressive social movements, was formed in an effort to rejuvenate left politics, while the Economic Freedom Fighters, a political breakaway from the ANC espousing a program of militant nationalism and radical redistribution, has rocked the ANC’s base. “The hegemony of the ANC is eroding” von Holdt says, but he cautions, “the future is uncertain. Despite evidence of a fracturing hegemony, the ANC still dominates the local, the communities; it remains a very powerful organization.”

Bourdieu, Fanon, and the Sociology of Violence

Von Holdt’s diagnosis of South Africa’s violent democracy is closely related to an effort to conceptualize violence in more general terms. In a compelling article in Current Sociology, he explores the high levels of violence associated with South Africa’s contentious politics, drawing on collaborative work with Michael Burawoy, published as Conversations with Bourdieu: The Johannesburg Moment (Wits University Press, 2012). “My contribution to that book,” von Holdt explains, “revolved around trying to read Bourdieu through South Africa – to identify gaps and silences in his contributions. At the same time, it was interesting to look at South Africa through Bourdieu, because his work concentrates on a finely-tuned sense of order and how order reproduces itself.”

In his article, von Holdt explores the dissonances and resonances between Bourdieu’s conception of symbolic violence and Fanon’s account of colonial violence. “In the colonial situation, symbolic violence doesn’t work in the way that Bourdieu suggests; it isn’t sufficient to explain order. As Fanon shows, real violence is needed as well. But at the same time, the concept of symbolic violence helps us to understand that what Fanon is talking about as the racism and violence of the colonial order isn’t simply physical and material; it is also symbolic.”

“What’s interesting about these two thinkers is that Fanon, especially in his mature work, engaged on the terrain of the colonial and postcolonial order, where violence and modernity go hand in hand; it’s a terrain where the modern is unequivocally violent. But Bourdieu – if you bracket his early experiences in Algeria – emerges entirely in the western context of a pacified society. What I find interesting is to turn back to Bourdieu, and ask whether western modernity works in the way that he proposes. I’m not so sure it does. Especially in the context of the current crisis in the west, these assumptions are starting to break apart. What happens to Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic violence in a context of mass unemployment? Where the state withdraws benefits? Where banks and corporations are dominant? It starts to break down.”

Does this reading resemble Jean and John Comaroff’s claim that the global South offers privileged insights into the workings of the modern world? Von Holdt demurs. “I’m a bit skeptical about that, because the North has always managed to preserve its exceptionalism. The fundamental issue remains how the North is able to dominate knowledge production and wealth extraction. That relation of dominance is not about to be superseded. It’s not as if the South is about to start dominating the North.” Nevertheless, von Holdt insists on the need for radical rethinking. “Certain analytical insights and conceptual innovations that one can develop in and for the South also involve rethinking the whole conceptual apparatus of the North, including its relation to Northern realities.”

Is it parallel to Raewyn Connell’s call for Southern theory? “I prefer to think of theory-making in the South. I find it difficult to imagine a wholly alternative way of thinking because our own thinking is already so western. How and from where do you recover an alternative knowledge?” The fact that South African sociology has been developed by individuals tied by language and history to the metropolis of the world-system, he suggests, has significant ramifications for knowledge production. “I’m one of the offspring of the white settler elite, so that’s the ground that I work on. We’re so bound together with western forms of knowledge that we have to think through and against them; however, others may explore the recovery of indigenous thought, which could lead to important interactions.”

Public Sociology in Post-Apartheid South Africa

From the limits of western sociology, our conversation turns to the challenges of public sociology in the perplexing and paradoxical context of post-apartheid South Africa. Von Holdt, whose career has swung between academia and activism, insists that public sociology cannot be a purely oppositional activity. “The progressive sociologist often imagines himself or herself as engaging with subaltern movements; that’s the force privileged by progressive sociological analysis, and through which sociology can achieve political significance.” Von Holdt’s research unit, SWOP, was founded on this vision, in close dialogue with COSATU’s militant unions in the 1980s. But with the transition to democracy, SWOP started collaborating with progressive government ministries. This experience leads von Holdt to question the utility of a sharp distinction between policy research and public sociology. “Policy sociology is thought of as a dirty business where you’re paid to produce results that people in power want to see. Effectively, it bolsters the status quo rather than being aligned with forces for change. When you work with unions, you often operate on the terrain of critique, but at the end of the day, what unions really want is policy-relevant knowledge because they need to negotiate. They need possible solutions to given problems, and that’s a policy question. So for me, the notion that public sociology is somehow a pure progressive form of knowledge – and conversely, that policy sociology is somehow tainted and corrupted – doesn’t work. There’s an interplay between the world of rebellion and the world of governance.”

In today’s South Africa, speaking truth to power has become ever more necessary. “We find ourselves shifting again. The practices and principles we forged in relation to unions don’t work anymore because of emerging divisions within them. The old rules don’t work, so our practices of public sociology shift all the time.” But for von Holdt, this doesn’t necessarily require reversion to a purely oppositional public sociology. “Whether you want to engage in a way that could make a difference to the way resistance is conducted, or to the way a society is governed, you’re in a constant compromise with power. And that is always uncomfortable. Some people, of course, are more comfortable with simply adopting a critical stance. However, conceptual innovation comes from grappling with a reality that challenges you all the time.”

Alf Gunvald Nilson <alfgunvald@gmail.com>

Karl von Holdt <karl@yeoville.org.za>