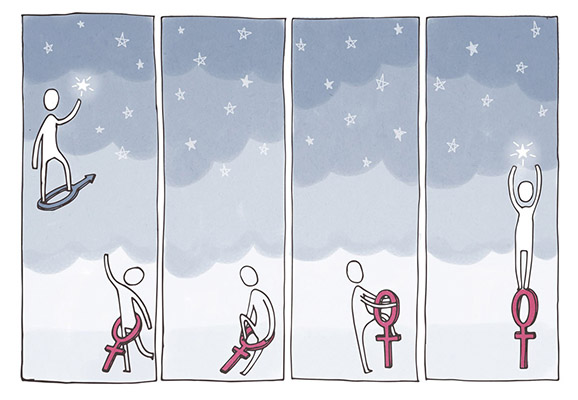

Gender and social inequality are key spheres of study and analysis in sociology, gender studies, and countless other disciplines. An important common finding in these research fields is that women account for a large proportion of the poor and marginalized worldwide. According to the 2018 World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, it will take 202 years to close the world’s global economic gender gap.

Economic inequalities take many forms; for example, according to The Global Gender Gap Report 2018 women are able to own land in only 41% of countries surveyed. In professional spheres, only 34% of managerial positions are held by women. The role of women in the informal economy is another gendered challenge. Women make up the majority of the informal economy, and are reported to spend twice as much time on unpaid tasks as men. Because the informal economy is unregulated, women are left uniquely vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Many of these statistics could be significantly improved through meaningful policy change. That said, women are their own best advocates; yet they remain largely underrepresented politically. Of 149 countries surveyed for the report, only 17 currently have women as heads of state. Further, only 18% of ministers and 24% of parliamentarians worldwide are women.

Despite great progress towards broader gender equality in some countries, there still remain significant gaps in opportunities for women based on the full range of their intersectional identities, such as race, class, and sexuality, among others. While some more privileged women benefit from the progress, others continue to live in precarious conditions. Within individual states, differences between women of varied social and cultural backgrounds are increasing. These differences have a great impact on social security and opportunities for women. For example, according to UNICEF data, the United States has a relatively low maternal mortality rate, ranking 54th out of 182 countries surveyed. At the same time, the maternal mortality of black women is more than triple that of their white counterparts in the US, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

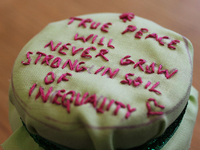

While many states are continuing to make progress, the rates of progress are varied. The Global Gender Gap ranks the Middle East and North Africa as having the largest regional gender gap, but their rate of progress to improve conditions for women is actually better than that of the North American region. It is estimated that South Asia could close its gender gap in 70 years - almost a century before North America, the Middle East and North Africa. When that region is further examined, however, one might ask if that statistic is remotely meaningful to displaced Rohingya women in Myanmar, who live in extremely precarious circumstances due to ongoing ethnic cleansing. Statistics such as these force us to question how we define and measure progress regarding gender inequality.

The contributions to this volume of Global Dialogue shed light on the considerable socio-spatial differences in how gender and social inequality are related and shaped. The purpose of the volume is to present a starting point for these different dynamics and create space for further research and discussion, ideally with implications for social and policy change for women.

Liisa Husu opens these considerations with the observation that, despite the great advances women have made in higher education across the world, the trend that the higher the position, the fewer the women, persists. In her paper “Gender Challenges in Research Funding” she discusses the implications of underrepresentation from the perspective of European and Nordic Countries.

Blanka Nyklová outlines in “Challenging Gender Equality in the Czech Republic” how neoliberal ideology and conservative attitudes shape gender and social inequality in Central Europe, with a focus on the Czech Republic. She uses the concept of distorted emancipation to highlight privileges accrued by some women at the expense of others.

In “Persistence and Change: Gender Inequality in the US” Margaret Abraham discusses how we observe successes in the fight for equality in the United States, coinciding with setbacks. She argues that these achievements towards equality and justice are not self-evident, and that we have to move forward in our social actions and in sociological analysis.

Lina Abirafeh examines gendered inequalities in the Arab context in her article “Gender and Inequality in the Arab Region”. The region has long suffered economic and political insecurities, compounded by socio-cultural obstacles and a system of entrenched patriarchy. This toxic combination stalls – and in many cases, reverses – progress toward gender equality. The region will not achieve peace or prosperity without full equality for Arab women.

Nicola Piper’s article “Gendered Labour and Inequality in the Asian Context” examines gendered labor and inequality in the Asian context, noting that their large, sustained population movements have become a focus for scholars and practitioners. In particular, female migrants are concentrated in feminized sectors and often lack rights and protections. Their challenges and vulnerabilities are at the heart of gender inequality in the region.

In his article “IPSP: Social Progress, Some Gendered Reflections”, Jeff Hearn reflects on the process and outcomes of the International Panel on Social Progress’ (IPSP) report. He focuses on the recommendations in the report on how gender should be conceptualized.

Birgit Riegraf, Paderborn University, Germany, and member of ISA Research Committee on Women, Gender and Society (RC32) <birgitt.riegraf@uni-paderborn.de>

Lina Abirafeh, Lebanese American University, Lebanon <lina.abirafeh@lau.edu>

Kadri Aavik, Tallinn University, Estonia and University of Helsinki, Finland <kadri.aavik@tlu.ee>