This year celebrates 30 years since the lifting of the Iron Curtain in Europe’s semi-periphery, or 30 years of uneven neoliberalization hailed as the only possible path to democracy. The ascent of democracy was seen as a move to meritocracy, erasing former power structures based on Communist Party membership. Media from the period shows that meritocracy, which justifies the inequality of those seen as undeserving on personal grounds, was cheered with much enthusiasm as enabling the leap towards the geopolitical center. Yet, the Czech Republic is currently run by an oligarchic Prime Minister who was a secret agent before 1989 and who, like most Czech billionaires, managed to translate his privileged pre-1989 position into economic power through the process of privatization. At the same time, almost one-tenth of the population find themselves in a debt spiral due to intentionally harmful distraint legislation, with some 70,000 homeless people and 120,000 more facing the loss of their home. Here I outline some of the consequences of the political rationality underpinning neoliberalization for social/gender inequality in the Central European Visegrad Group countries, with a specific focus on the Czech Republic. Using the fate of the discipline of gender studies, I further explore the impact of this rationality when applied to questions of equality and justice.

Neoliberalism has become a conceptual shortcut that explains the causes of inequality, including gender inequality, in today’s globalizing world. As such, neoliberalism is understood as a return to the free market as the ultimate determinant of all aspects of life. Critical theorists have attempted to counter this oversimplification by examining its functioning in interconnected areas. In 1998, French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu associated neoliberalism with the destruction of collectives and toxic atomization of the workforce, which was eroding the capacity of individuals to resist the forces of global capital. For almost two decades now, British cultural theorist Angela McRobbie has focused on how cultural representations of economic empowerment based on approaching one’s life as a project – such as in the literary and film character, Bridget Jones – impact the lives of young women who identify with her. US political theorist Wendy Brown has focused on the effects of market logic not just on the economic dimension of social life but, more importantly, on the political rationality of democratic institutions.

Neoliberalization and gender in the Visegrad countries

The above authors use concrete examples, yet they are often treated as offering a universally valid theory of neoliberalism, leading to calls for a contextualized study of the phenomenon. Central European Visegrad countries provide a laboratory within which to observe the consequences of differential implementation of the instructions of organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to facilitate democratization. Especially after 2000, critical studies of neoliberalization in its geopolitically contingent form have grown in number. Analyses of gender inequality and its transformation show that the modern emancipation project has resulted in what Zuzana Uhde calls “distorted emancipation,” a situation where the empowerment of certain groups of women comes at the expense of other women through the commodification of previously outside-of-market spheres such as care. Distorted emancipation is not only incomplete, but furthers new injustice and cannot be fought without grasping the key role played by capitalism in sustaining it.

In the Czech Republic, women constitute around 20% of members of parliament; the gender pay gap persists at 22% in general, and at 10% for the same position in the same enterprise; women make up 98.5% of parents taking what is one of the longest parental leaves in Europe; and sole parent families are headed by mothers in 90% of cases. Women have faced rising levels of economic instability since 1989 and are disproportionately more likely to be threatened by poverty; elderly women face higher risks of poverty, with economic and social inequality exacerbated in specific regions of the country and by ethnicity/migrant status. More importantly, gender culture in the Czech Republic and Visegrad Group countries in general, is marked by conservatism and sexism, allowing for the distorted emancipation to go unchallenged; women’s emancipation and efforts to increase it are even blamed for some of the region’s economic woes.

Scholars specializing in gender studies have demonstrated how conservatism in gender relations and neoliberalization have mutually sustained each other. Radka Dudová and Hana Hašková show that parental leave policies after 1989 were just an extension of those designed before 1989 as part of refamilialization policies. Libora Oates-Indruchová and Hana Havelková focus on the unacknowledged contribution of the women’s and feminist movement to some of the Communist-era emancipatory policies, while Kateřina Lišková shows how a double standard around sexuality was reintroduced in late-1960s medical discourse and has prevailed since. None of these contributions would have been possible without the proliferation of gender studies and feminist theories in the region.

The fate of gender studies

The fate of gender studies in the region may help us understand the persistence and mutation of gender inequality in a democratic project underpinned by neoliberalism. The establishment of the discipline was linked to the funding of local feminist activism by US and later EU donors in a context of scarce local funding. Gender studies was introduced in two major Czech universities around 2004, partly due to the window of opportunity provided by neoliberal higher education reforms necessitating larger student numbers. However, the very same political rationality has facilitated the recent dismantling of gender studies programs not just in Hungary but also in the Czech Republic, negatively affecting the capacity to do gender-oriented research in Central Europe. As Wendy Brown has noted, neoliberal rationality is ultimately normative – the rule of market logic is not assumed but is actively institutionalized at the expense of any differently-founded rationality, such as the emancipatory rationality underpinning much of the feminist project. In a gender conservative region marked by an extraordinarily easy rejection of any openly political action targeting unequal social relations as Communist-era social engineering, the neoliberal political rationality first aligned well with some feminist efforts, including those striving to institutionalize gender studies. The ban of gender studies in Hungary uses exactly the same political rationality but, importantly, frames it as economic (on the false grounds of lack of demand for gender studies graduates in the labor market) and therefore apolitical. This serves the political purposes of countering possible social critique and earning popularity with the anti-gender movement (described on these pages by Agnieszka Graff and Elżbieta Korolczukin 2017). In the Czech Republic, the closing of the Brno gender studies program in 2018 was justified by claims that the program was not “profitable,” in that it failed to attract students in a public education system dependent on student numbers.

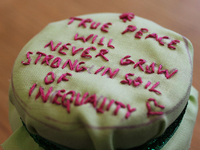

The parallel between the two cases is striking even if the motivations are – at least explicitly – different. While in the Hungarian case the political reasoning became apparent when the discipline was painted as strictly ideological and not scientific, in the Brno case neoliberal political rationality was institutionalized by the university leadership when it failed to address the ethics of their decision. To truly counter gender inequality – in its economic dimension, but also in terms of tolerance for sexual violence and endorsement of sexual harassment by public figures and politicians – its embeddedness in neoliberal political rationality must be made explicit. If we are to successfully counter the normative tenets of neoliberalism, we have to acknowledge these dependencies, as they otherwise threaten to blunt the normative logic underpinning feminist critiques of social and specifically gender inequalities. The 30 years since 1989 have clearly shown that neoliberal political rationality is doomed to fail when tasked with removing inequality, since it is in fact invested in protecting its actual roots.

by Blanka Nyklová, Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Science, Czech Republic <blanka.nyklova@soc.cas.cz>