The provision of replacement incomes to adults who are physically capable of work has always been among the most controversial questions in social policy. Intended to protect against income loss due to involuntary exclusion from paid work, unemployment benefits have long been criticized by some as a subsidy to voluntary withdrawal from it. Such criticisms have become particularly audible in media discourse and political debate in recent decades. Policies that have tightened so-called benefit conditionality – increasing the requirements placed on jobseekers to prove their efforts to get back into work, backed up with sanctions in the form of benefit reductions or suspensions for non-compliance – have been perhaps the most prominent feature of unemployment benefit reforms in European countries over the last quarter century. Such measures have sought to respond to heightened public concern about abuse of unemployment benefit provisions, while paradoxically reinforcing a general perception that such abuse is widespread.

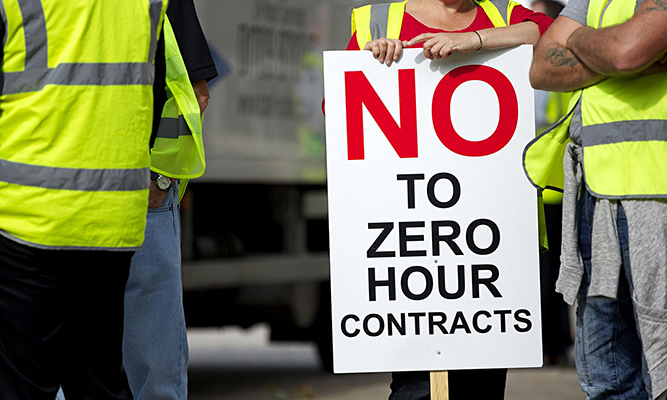

Fragmentation of work and uncertainty of employment

This long-standing concern with abuse of unemployment benefits, and the related discourse around the responsibilities of jobseekers, elides the key challenge that unemployment benefit policy faces in the early 21st century, however. Unemployment benefits were conceived in labor markets where dependent work was increasingly being reorganized to provide (male) workers with longer hours and more continuous employment. “Decasualization” of the workforce was occurring as a result of the growth of manufacturing, but was also being actively pursued as an objective of both public policy and collective bargaining. Today, by contrast, the service-dominated economies of rich democracies are seeing an explosion of varying types of non-standard employment relationship, and especially the return of short-time and discontinuous (e.g. on-call) work, sometimes disguised as self-employment. New technologies have further facilitated the fragmentation of work tasks, hastening the arrival of a “gig economy.” Governments are at best reluctant to counter these trends, and often actively promote them as a route to growth, competitiveness, and increased employment. Weakened trade unions have proved relatively powerless to resist. We are slipping into a new age of casual work.

For many today, and particularly those with low skills, unemployment is thus a very different type of “social risk” to the one unemployment benefits were established to compensate. No longer an occasional period of absence of work between stable, long-term engagements, unemployment has increasingly become a recurring feature of laboring lives characterized by a succession of more-or-less short-term, irregular, and insecure periods in work. The boundary between unemployment and employment has grown distinctly unclear. Should a worker employed for the first and last weeks of a month, but without work between times, be considered to be employed or unemployed in that month? Is the economic status of a worker who held two part-time jobs concurrently but lost one defined by the job they still have or by the loss of the other?

In-work benefits: making work pay?

The policy trend that is truly symptomatic of the complex challenges facing unemployment benefit policy in this new labor market context is not the pervasive turn to stricter conditionality, but rather the more fitful and uneven development of in-work social security benefits. Introduced and expanded in a number of European welfare states in recent years, whether as new stand-alone entitlements or through modifications to the eligibility criteria for unemployment insurance or assistance benefits, in-work benefits give lie to the belief that the key reason for people being out of work might be their lack of effort, motivation, or responsibility. In-work benefits exist simply because in contemporary European labor markets the reemployment opportunities available to many jobseekers frequently provide lower rewards and less security than out-of-work benefits, despite the modest value of the latter.

Supplementing earned incomes through the social benefit system is a policy approach fraught with difficulties of its own, however. If they are to offer meaningful incentives to the unemployed to re-enter work, in-work benefits need to provide workers not only a supplement to their work income but also reassurance that should the new job be quickly lost they will not find themselves worse off than if they had not taken the job in the first place. This opens the door to a situation where periods of work and non-work can be almost indefinitely alternated, potentially institutionalizing short-term, intermittent employment relationships through a permanent implicit subsidy from the benefit system. Proposals for a universal basic income share precisely this flaw. Where in-work benefits are targeted on lower incomes to limit their cost, they tend to produce very high effective tax rates for workers seeking to increase their hours or earnings, locking workers into low-paying employment even more strongly still.

Flexicurity or generating stability?

Faced with these real policy challenges, some governments in Europe have recently – as with the 2019 reform of unemployment insurance in France – announced significant restrictions to in-work benefits, again placing their faith mainly in conditionality to move the unemployed into stable employment. Where in-work benefits are maintained, “in-work conditionality” has also been introduced in an attempt to use tighter behavioral controls on in-work benefit claimants to promote progression within employment, as under the new Universal Credit system in the United Kingdom. In both cases this seems to place the responsibility for the realities of contemporary low-end labor markets on the shoulders of those whose economic opportunities are most directly limited by them.

The real crux of the matter is that it is simply very difficult to adapt the cash transfer systems at the heart of modern European welfare states, with their attendant logic of compensating risks, to a labor market context in which work has become predictably insecure for so many. “Flexicurity” – the recently fashionable policy ideal of combining labor market flexibility and social security – is a neat portmanteau, but offers little practical guidance for how an income maintenance system can protect the casually employed without generating spiraling costs, unintended consequences, or both at the same time. Unemployment protection will continue to make sense only if European labor markets can again generate a basic level of stability in working lives. This requires better regulation of employment, not stricter controls on the behavior of vulnerable workers.

Daniel Clegg, University of Edinburgh, UK <Daniel.Clegg@ed.ac.uk>