The term intersectionality addresses the intersections and entanglement of social structures and identities. Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, it uses the metaphor of a crossroads: a highly frequented place where individuals of different genders, sexualities, social classes, or racialized identities are constantly in danger of being run over. This metaphor has been successfully employed in analysis and debate concerning social inequalities because of its capacity to depict the intersections of different forms of social positionings and discrimination. By replacing the “add-on” approach to categories of difference in power relations (gender and class and “race”), intersectionality established a new agenda: it captures both the structural consequences and the processual dynamics of interactions between three or more axes of power and subordination.

Crenshaw’s idea of intersections between systems of oppression found global resonance during the UN World Conference against Racism in Durban in 2001. Today, the concept of intersectionality has long left the fields in which it originated: gender studies, critical race studies and law. It is now used in sociology and social work, health studies, education, social geography, anthropology, psychology, political science, literature studies, and even architecture. In gender studies, intersectionality became a keyword for course offerings in graduate and undergraduate programs. Conferences, special issues of academic journals, and book publications devoted to intersectionality abound. One can now speak of the field of “intersectionality studies.”

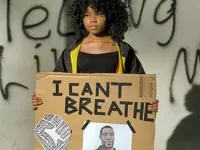

As it traveled from the US to Europe, the notion of intersectionality was taken up in many parts of the world. During these travels, the concept has been changed and adapted to local conditions and historical contexts. In Europe, for example, ethnicity and religion became relevant categories for analyzing discrimination within migrant populations; while in India, “caste” was included as a category that is essential for understanding social inequalities. More recently, generational differences have emerged in how intersectionality is conceptualized – or should be. Recent movements like Black Lives Matter have influenced debates on race and struggles against racism, fueling innovative work in the field of intersectionality.

Understanding these developments requires us to look at the history of intersectionality through the lens of the present. What is it that brings critical scholars and activists back to intersectionality again and again? What is it about the concept of intersectionality that enables it to constantly reinvent itself? And finally: How is intersectionality elaborated, re-worked, and deployed for different purposes and different terrains?

These questions are central to the Routledge Handbook of Intersectionality Studies, which we are now editing and will be published in 2023. The Handbook covers a wide range of topics within the field of intersectionality studies from international and interdisciplinary contributors. For this issue of Global Dialogue we have asked several authors to provide a shortened version of their chapters. The result is a preview of some of the ways intersectionality has been employed to understand social, cultural, and geopolitical inequalities. Ann Phoenix begins the conversation by considering the ways the histories of slavery and colonialism haunt the present, showing why they need to be part of how we think about intersectionality globally. Barbara Giovanna Bello continues with an intersectional look at two of the most important social movements of the present – Black Lives Matter and #MeToo – which began in the United States, but have since become global. Ethel Tungohan shows how intersectionality is essential for understanding the recent migrant care workers’ movement in Canada where it was clearly necessary for different social movements to join forces in order to undermine oppression. Turning to the debates which have emerged within the field of intersectional studies, Amund Rake Hoffart takes a critical look at the search for a pure intersectional metaphor which will eliminate all the problems with the concept, arguing instead for the “need for messiness” in research on intersectional inequalities and configurations of power. Finally, taking up the international call for a methodology for intersectional research, we (Kathy Davis and Helma Lutz) show how the deceptively simple procedure of “asking the other question” can help us analyze the strategies people use to resist or accommodate power in their everyday lives.

Taken as a whole, this dialogue shows some of the ways intersectionality has been influential in how scholars and activists alike can think about inequality, power, and social transformation, both locally and globally.

Helma Lutz, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany <lutz@soz.uni-frankfurt.de>

Kathy Davis, Free University Amsterdam, The Netherlands <<k.e.davis@vu.nl>