The #Black Lives Matter (BLM) and #MeToo movements have become globally viral since 2013 and 2017, respectively. Due to the amplifying effect of social media, they have catalyzed international attention to the persistent and systemic violence confronting women and Black people in the US and beyond.

Origins

BLM was co-founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, and is considered the first Internet-based movement of its kind. Its leadership has been Black, female and queer ever since. The #MeToo movement has a different history: founded by Black activist Tarana Burke in 2006 with the aim of healing trauma of sexual violence against women, young people, queers, trans people, and those from Black communities with disability, its fast online journey started when, during the Harvey Weinstein scandal in 2017, celebrity Alyssa Milano – unaware at the time of the earlier grassroots MeToo movement – called upon women worldwide to share their experiences of sexual abuse by using the #metoo hashtag.

The “both/and” perspective

One may ask why two movements initiated by Black women, intentionally intersectional since their inception, face challenges when it comes to making the “both/and” perspective work effectively. We see Black male activists progressively represent themselves as advocates for their community and as the primary target of racist violence by law enforcement officers; meanwhile, White women’s requests to compete in the labor market, without the threat of sexual abuse, seem to dominate the scene; but Black women’s voices and experiences are increasingly absent. In what follows, I summarize some possible explanations for their invisibility and reflect on how an intersectional approach could hopefully contribute to remedying it.

Unequal questions of social justice

Firstly, at the structural level, the different status enjoyed by gender and race as stand-alone categories needs closer analysis, since it affects their mutual interplay and that with other categories in hierarchical power relations. In fact, the BLM movement primarily calls upon Black people to address White supremacy and the reproduction of violence along the line of race. The conservative counterclaims, like the “All Lives Matter” and “Blue Lives Matter” groupings, particularly minimize Black women’s and most disadvantaged Black people’s demand for dignity. In its turn, #MeToo addresses virtually all women (more than half of the world population): it seeks to dismantle patriarchy, but it expresses this more clearly around access to the “room” of power without the threat of sexual violence, a place that is even harder for Black women to access. All in all, both movements raise questions of social justice, but they do so differently.

The self-perpetuation of privilege

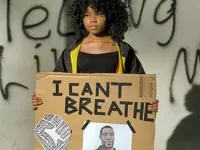

Secondly, the US and international mainstream media have played a role in furthering Black women’s invisibility. News and images of brutal killings of Black men and their last words – “I can’t breathe” – still thunder loudly in our ears and souls, but those of murdered Black women are absent. Similarly, sexual abuse denounced by White women – celebrities or not – have overshadowed that reported by “other” women. In this context, “class” matters in both movements. The prism of class–race–gender helps reveal mutually constructing systems of privilege that are crystallized in the media system – where White people, including women, are in a better position to attract attention – and reproduced through information.

These first two observations possibly explain the wider support received by #MeToo and the downplaying of Black and minority women’s experiences, while suggesting possibilities of how to subvert power relations and include “all” voices.

Why we need intersectionality

Thirdly, it may be suggested that the murder and sexual abuse of Black women are still perceived as too specific to represent “universally” all women’s and Black people’s sufferings. So, an intersectional approach has the potential to transform the public discourse still based on the assumption that racist and sexist violence are what happens, respectively, to Black men and White women.

Fourthly, intersectionality helps explain how social constructions fuel the domination/subordination of bodies, which are de-humanized in the BLM cases and exploited in the case of #MeToo. Portrayals of Black women as aggressive Sapphires, or holding “superhuman” strength, or as hypersexualized Jezebels assumed to be available may instrumentally serve to justify the abuse of state force against them or non-consensual sex, and to question their credibility. This surfaced in the Weinstein case too: out of many denouncements, he specifically discredited Black Kenyan-Mexican actress Lupita Nyong’o. At the same time, the representation of Black men as “rapists” of White women often led to unfounded incriminations and legitimized their lynching in the past, possibly explaining the reluctance of some of them to support the #MeToo motto, “Just believe women,” which may also impact their solidarity with Black women.

Moving forward

Lastly, as a heuristic device, intersectionality focuses on the implications of the interaction between power structures, but political decisions determine whom to support and how, as Keisha Lindsay underlines. In both movements, many supporters are still engaged in a single axis struggle, while their founders and other activists are frantically seeking to make the still invisible people visible: their initiatives deserve greater media and online attention worldwide. Hence, the #SayHerName project was launched in December 2014 by the African American Policy Forum (AAPF) and the Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies (CISPS) to tackle violence by the police against Black women (including trans and gender non-conforming women); the original #MeToo and the #UsToo movements seek to tackle sexual abuse against women of color, unskilled workers, and LGBTQI+ people.

As a way forward, I suggest that the characteristics of the Internet could be better used to raise the “intersectionality question” globally. In fact, if the transnationality and amplification of Web communication have allowed emphasis to be placed on White women and Black men, they have also made it blatantly evident that “someone” was missing in the narration, and have paved the way for prompt reactions about “who” was not there and “why,” providing room to discuss current gaps. In this “virtual” space, BLM and #MeToo could maximize their offline and online “intersectional” agendas by building coalitions. If we recall the American lawyer and activist Mari Matsuda: “we cannot, at this point in history, engage fruitfully […] without engaging in coalition, without coming out of separate places to meet one another across all the positions of privilege and subordination that we hold in relation to one another.”

Barbara Giovanna Bello, University of Milan, Italy, and Board member of ISA Research Committee on the Sociology of Law (RC12) <barbara.bello@unimi.it>