Language, in both its everyday and academic forms, is loaded with metaphor. If you start looking for metaphors in a text, they are likely to spring up like mushrooms. Metaphors make use of tropes: expressions that shift the familiar meaning of words so that they depict something else. Metaphors such as a broken heart, a bad apple, one’s moral compass, late bloomers and double-edged swords make use of well-known objects from mundane settings and transfer them into new, sometimes surprising, ones. Locating the wealth of metaphors in our everyday and academic language illustrates why they are something we “live by,” as it was put in the classic work on metaphor by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson from 1980. Far from being a peripheral phenomenon of language, something extraordinary that belongs to the realms of poetry and rhetoric, metaphors deeply influence our everyday thinking and actions.

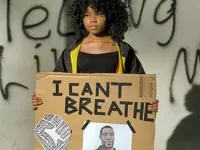

Crenshaw’s traffic intersection

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s 1989 essay “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” elaborated the concept of intersectionality through the metaphor of a traffic intersection. By visualizing Black women’s experience of discrimination as the experience of being run over by traffic from multiple directions, Crenshaw provided particularly evocative imagery to accompany her analysis of legal cases in the USA, where Black women were falling through the cracks in the US anti-discrimination doctrines. Although the traffic intersection has since been taken up as intersectionality’s central image, it has also received its share of criticism. Most objections center on the additive dimensions of the image of the traffic intersection: it portrays social categories – like gender, race, class and sexuality – as separate and independent, making it possible to add them to each other. It seems hard to deny that the image of the traffic intersection is additive in the sense that it separates independent roads that lead into and out of the intersection. In the three decades that have passed since the publication of Crenshaw’s essay, an abundance of – more and less eccentric – alternative metaphors have been proposed. This, then, has also become one of the important ways in which intersectionality travels: the idea has journeyed far and wide by continuously being given new interpretations and elaborations through metaphor and analogy.

There’s more than one way to skin a cat!

Interestingly, some alternative metaphors for intersectionality are more abstract than the traffic intersection they are intended to replace, for instance, axes, interferences, configurations, assemblages, fractals, interstices, vectors, topographies, and disorderly spaces of emergence. For those looking for metaphors in more tangible arenas, the sphere of cooking and baking is evidently an inspiring one, as intersectionality has been likened to sugar, cookies, a layer cake, the swirls in a marble cake, batter, and a stew. There is one aspect of cooking and eating that has had an especially alluring effect on scholars in search of better intersectionality metaphors: the way ingredients mix, intermingle, and flow into each other; parts becoming wholes, wholes becoming parts; different ingredients blending, spilling over, and being chewed up together. One example among the mountain of food metaphors is Shannon Sullivan’s stew, presented in her 2001 book “Living Across and Through Skins.” In contrast to a fondue, where ingredients melt together and disintegrate, the vegetables in Sullivan’s stew retain their “identity” in the pot, but at the same time they are transformed by interacting with other vegetables. Thinking of a stew as a metaphor for intersectional social relations and identities, the vegetables in the pot illuminate the dynamic and mutually shaping relationship between different parts of one’s social identity, such as categories of race, gender, class, sexuality, age, dis/ability, and so on.

The messy mountainous intersection

Other scholars have continued to work with the traffic imagery of roadways and crossroads. In her 2011 essay “Intersectionality, Metaphors, and the Multiplicity of Gender,” Ann Garry sketches the step-by-step addition of more elements to the traffic intersection: elements that build upon, but at the same time complicate, Crenshaw’s original metaphor. To make it more fluid and better able to capture a thorough blending of oppressive systems, Garry adds more streets, more cars, and a roundabout. Nevertheless, these added elements still cannot redeem the restrictive horizontality of the image of the traffic intersection. To do so, we must venture beyond the flat structure of the roundabout. What is needed is an element of verticality to convey how structures of privilege and oppression work together and relate to each other. At this point, Garry turns to mountains and then also introduces running liquids to accompany the image of the mountain. Again, the motivation is to ensure that the imagery remains fluid, not solid and discrete. Garry’s remake results in something like the following: liquids run from mountains to an intersection with a roundabout in its center and where many streets and cars meet. If this image appears messy, Garry assures us that this kind of messiness is exactly what we need in our metaphors to help us understand the complexity of intersectionality.

There is no pure messiness

What drives this search for alternative metaphors for intersectionality? The quest for new and improved metaphors seems to be fueled by the widespread dissatisfaction with intersectionality’s central image. The traffic intersection metaphor simply does not meet the requirements: it is too reliant on additivity of separate streams to suffice. That is to say that the “right” metaphor for intersectionality must also be one that is unsullied by additivity. At this point, I am reminded of Garry’s insistence on the need for messiness in our intersectionality metaphors. However, the quest for the right metaphor for intersectionality appears, paradoxically, to aspire towards a pure version of the impure; that is, it is an attempt to carve out a metaphor that is free from additive pollution. Aspiring towards such ideals of purity seems, to me, to be the very opposite of messiness, and something that might actually hamper our intellectual and metaphorical imagination. Would not taking “the need for messiness” in our metaphors seriously, instead require us to acknowledge the additive dimensions of our thinking, and see them as a potential resource rather than an embarrassment?

Amund Rake Hoffart, University of Oslo, Norway <a.r.hoffart@stk.uio.no>