Read more about Open Section

Buffalo, NY: Good Practice in Refugee Resettlement

by Ayşegül Balta Özgen

February 21, 2020

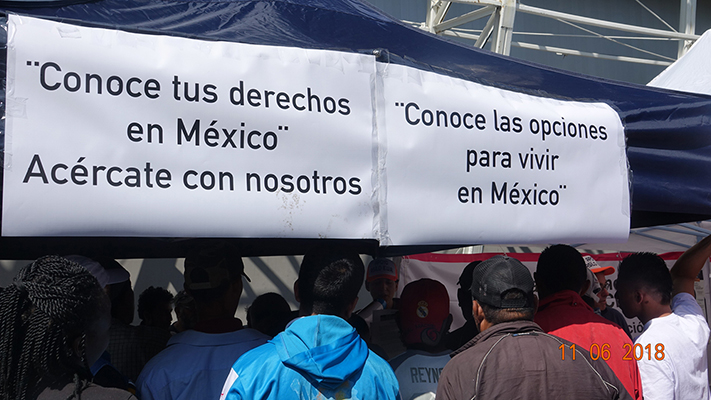

On a spring afternoon in May 2019, I saw Lucia and Hector once again. This was the third time I had seen them over a period of six months. This time they were at the US-Mexico border city of Tijuana. Lucia and Hector were part of the thousands of Central American migrants who in October and November 2018 crossed Mexican territory as part of the so-called Central American caravan. The migrants used this caravan as a mobility strategy to reach the US-Mexico border. The first time I met Lucia and Hector was in Mexico City on November 5, 2018, during my visit to the stadium that served as a shelter for the thousands of participants in the caravan who began arriving in the city on November 3.

The first caravan – there were four in total in 2018 – set off on October 12 from the city of San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and arrived in Tijuana, Mexico, on November 12. Central American migrants crossing Mexican territory in a quest to reach the United States is nothing new. According to Marta Sánchez Soler, coordinator of the Mesoamerican Migrant Movement (MMM), around 800 to 1000 Central American migrants enter Mexico daily. It is estimated that in 2014, for instance, approximately 392,000 Central American migrants had crossed Mexican territory, with the number decreasing slightly to 377,000 in 2015. If the presence of Central Americans crossing Mexican territory is not a new phenomenon, why did the migrant caravan attract so much attention both nationally and internationally?

Human rights organizations have demonstrated that mass abductions have become a permanent, large-scale extortion system against migrants in Mexico. In her book Violencias y migraciones centroamericanas en México, María Dolores París Pombo asserts that migrants are exploited in criminal and sexual markets along the migratory route between the southern and northern borders of Mexico. In this context, the visibility of thousands of Central American migrants was the mobility strategy that allowed them to travel the Mexican territory in a safe, economically accessible, and fast way to reach the border between Mexico and the United States. Thus, though forming a caravan as a mobility strategy to cross Mexican territory was not new, this time a combination of factors made it different. First, there was the massive number and heterogeneity of people – young families, single mothers with children, young single men, unaccompanied minors, LGTBQ people, and a significant number of elderly and handicapped people – who rapidly joined the caravan. Second, there was the swiftness of their organization. Third, there was the determination of thousands of Central Americans to travel main roads, demanding their right to free and safe transit through the territory.

Why were these people leaving their homes, risking their families’ lives, and setting out for the US-Mexico border? The answer is complex and each country in the Central American region has its own historical backstory to tell. A recent report entitled “Disorder by design: a manufactured U.S. emergency and real crisis in Central America,” published by the International Rescue Committee, sheds some light on the background that led up to the migration. The report states that Salvadoran asylum seekers who reached the US arrived with severe levels of psychosocial stressors that had been compounded through the generations, as families endured decades of civil war, state violence, poverty, natural disaster and, most recently, pervasive and indiscriminate gang violence. A similar history is shared by Guatemala with a history of a 36-year civil war – from 1960 to 1996 – with a death toll of approximately 200,000 people, mostly indigenous descendants. For Honduras, the tipping points were the high level of corruption, the 2009 coup d’état, poverty, and extreme gang violence that has led thousands of Hondurans to flee their country. Under these circumstances, life had become unbearably dangerous and impoverished for millions of Central Americans.

On November 11, the first group of about 300 people from the caravan began arriving in Tijuana. According to a report by the Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF), a research institute located in Tijuana, it was estimated that about 6,000 people stayed at a sport complex facility which was enabled by the municipal government. In a report released on December 13, COLEF discussed five possible scenarios for those Central Americans still in Tijuana: (1) seek asylum in the US; (2) apply for refugee status in Mexico; (3) stay in Tijuana and find a job; (4) experience voluntary or forced repatriation to their countries of origin; and (5) cross the US-Mexico border surreptitiously. To this list, I add a sixth scenario: moving to another US-Mexico border town. This last possibility was the choice of Lucia and Hector. The second time I saw Lucia and Hector was in Tijuana in late November 2018, several weeks before they left Tijuana for Reynosa, Tamaulipas – a trip of 1,112 miles and to one of the most dangerous border cities in Mexico – in the hope, according to them, of getting a construction job in that city.

Several lessons can be drawn from the 2018 caravan. First, as a mobility strategy, the caravan represented the duality between the visibility it gave to the thousands of Central Americans crossing Mexican territory and the invisibility of these migrants once they were stranded on the US-Mexico border. Second, while the collective mobilization of people who joined the caravan was one of the decisive factors that helped them reach the border, today, that collective mobilization is gone as people have dispersed to Tijuana and other border towns in Mexico in search of their own survival. That puts caravan members in a highly vulnerable position. Third, this caravan revealed to the world the migratory crisis that exists in the Central American region. It is estimated that the number of Central American migrants arriving at the US-Mexico border could reach up to one million by the end of 2019. Fourth, the Mexican government faces a complex plight as a result of this Central American migratory crisis. Mexico’s southern border does not have the infrastructure to take care of the thousands of migrants – Central Americans, Africans, Cubans, Haitians, and other transcontinental migrants – who are stranded there waiting to continue their way to the northern border. Meanwhile, at Mexico’s northern border, the shelters for migrants are overcrowded with the thousands of migrants who have managed to arrive and are waiting to cross to the US either to request asylum or, in the worst-case scenario, to cross clandestinely to the United States. Lastly, today thousands of Central American migrants face uncertainity and vulnerability both in Mexico and in the US. In many cases they survive thanks to the empathy, solidarity, and compassion of individuals and civil society organizations that support and help people like Lucia and Hector in their search for a better life.

Veronica Montes, Bryn Mawr College, USA <vmontes@brynmawr.edu>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: