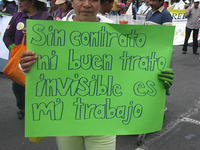

Senior home care: new care markets and precarious migrant work

Like many other countries, Austria, Germany, and Switzerland are increasingly confronted with what are being called “care gaps.” While their populations grow older, informal care capacities within families diminish, as the welfare state is reconfigured according to the now dominant adult worker model. At the same time, the state increasingly withdraws from the provision of social services – especially in long-term senior care. This has led to the emergence of a for-profit market that mediates transnational home care arrangements: care is outsourced to (mostly female) circular migrants from the new EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe. These workers care for and live with seniors in their private homes for a few weeks or months at a time (live-in care). In this rapidly growing and highly competitive care market, brokering agencies play an increasingly important role. Although they have formalized the previously informal sector to some extent, this has not markedly improved working conditions: live-in care workers are often expected to be on call around the clock and their salaries undercut local wage levels by far. Although live-in care has emerged as a highly precarious field of work in all three countries, its differential regulation has shaped public debates and opportunities for critique.

Austria: self-employed care workers

In Austria, live-in care is regularized as a self-employed profession. Working time or wage regulations do not apply to care workers. This makes the arrangement a flexible and comparatively cheap solution for households and for the Austrian welfare state. Nevertheless, the self-employment model has remained contested. Its opponents argue that – contrary to the ideal of care workers as independent market players – agencies heavily influence working conditions. For instance, they largely determine prices as well as salaries. Self-organized care worker initiatives thus call for abolishing what they see as bogus self-employment. Agencies and the Chamber of Commerce – which formally represents both agencies and workers – plead for further formalizing and professionalizing the existing model. The Austrian quality seal ÖQZ-24, for which agencies can voluntarily apply, can be seen as one result of agencies’ lobbying work. It designates an attempt to reshape market competition in favor of agencies which commit themselves to minimal standards. As the quality seal aims at improving the quality of care (rather than the quality of work), the seal affects the working conditions only indirectly and does not treat them as an issue in its own right. Struggles by trade unions and care workers for better working conditions have intensified in recent years, but so far have had little impact on the field.

Germany: posted care workers

In Germany, specific regulation for live-in care outside of generally applicable legislation does not exist. This is reflected in the multitude of legal frameworks to which agencies refer. Most agencies use the posting model: care workers are employed by agencies in the sending countries, which are supposed to pay their social security contributions. Still, agencies must adhere to basic working conditions in Germany (such as minimum wage and maximum working hours), even though these regulations are commonly circumvented. The transnational character of this work and the specific location of the workplace in private households hamper adequate control of working conditions. Furthermore, trade union representatives and other stakeholders criticize the regulatory gap and the subsequent lack of social protection for the workers. Achieving legal certainty is also a central goal of the industry – represented by the business interest association VHBP. Moreover, agencies strive to become officially accepted as a new pillar in the German long-term care sector and to shape legislation in their interest. This can be interpreted as an attempt to institutionalize the sector from below. On the part of the care workers, social media has become an important tool for communication and informal knowledge exchange – but to date, political self-organization in Germany is still in its infancy.

Switzerland: care workers as employees

In Switzerland, live-in care is formalized as an employment relationship. Only agencies headquartered in Switzerland can lease workers to private households (personnel leasing) or broker arrangements in which workers are employed directly by households (personnel placement). In contrast to Austria and Germany, self-employment or posting are prohibited by law. In addition, live-in care has not been institutionalized as an additional pillar in the long-term care regime. Financial support by the state is limited to (medical) nursing services. Thus, people have to pay for live-in care out of their own pockets. In terms of labor law, work in private households is exempted from the Federal Work Act. This means that live-in caregivers do not enjoy the same protection as other workers in terms of maximum working hours or night work, for instance. And while the applicable law defines a minimum hourly wage, this is largely ineffective since on-call duty is not bindingly regulated. In recent years, there has been an ongoing regulatory and media debate which has problematized the precarious working conditions in the sector. In contrast to the other two countries, (self-)organized and unionized care workers have played a key role in it.

Conclusion: live-in care as an intrinsically problematic model

Comparing the three countries we find that – especially in Germany and Austria – brokering agencies and their organizations have become powerful players in shaping regulations. Meanwhile, migrant workers’ voices have remained largely absent. In the Swiss case, the formalization of live-in care as an employment relationship has facilitated grassroots organizing of workers and union representation. This has brought workers’ concerns to public attention.

In spite of these differences, the live-in care model intrinsically builds on highly precarious working conditions for circular migrant workers in all three countries. In addition, it diminishes available care resources in Central and Eastern Europe. Based on these insights, we caution against further institutionalizing live-in care as a pillar in the long-term care regime. It can only ever be an exploitative quick fix. Solving the “care gap” sustainably requires a more fundamental revaluation of care work so that senior care can be provided by live-out workers who earn enough to live locally.

Brigitte Aulenbacher, Johannes Kepler University, Austria and member of ISA Research Committees on Economy and Society (RC02), Poverty, Social Welfare and Social Policy (RC19), Sociology of Work (RC30), and Women, Gender, and Society (RC32) <brigitte.aulenbacher@jku.at>

Aranka Vanessa Benazha, Goethe University, Germany

Helma Lutz, Goethe University, Germany and member of ISA Research Committees on Women, Gender, and Society (RC32), Biography and Society (RC38), and President of ISA Research Committee on Racism, Nationalism, Indigeneity, and Ethnicity (RC05) <lutz@soz.uni-frankfurt.de>

Veronika Prieler, Johannes Kepler University, Austria and member of ISA Research Committees on Poverty, Social Welfare, and Social Policy (RC19), and Women, Gender, and Society (RC32)

Karin Schwiter, University of Zurich, Switzerland <karin.schwiter@geo.uzh.ch>

Jennifer Steiner, University of Zurich, Switzerland