It is widely claimed that the rise of digital labor platforms is reshaping the future of work. While some praise the “platform economy” - both online web-based platform work (“crowd work”) performed remotely and location-based platform work carried out in a specified area - for its promise of freedom and flexibility, research shows that the platform economy is deepening the casualization of labor and shifting risks such as occupational health and safety onto workers.

Much of the discussion assumes digital platforms are creating “new” types of work. However, most of these jobs have been around for a long time: metered taxis, restaurant food delivery services, and domestic cleaners. What, then, is “new” about emerging forms of gig work? And how are digital platforms changing what it means to be a formal or informal worker?

What is “new” about platform work in the Global South?

What is perhaps most distinctive about economies of the Global South is the high degree of informality. “New” forms of gig work take place in a context where informal work relations are already the norm rather than the exception. An ILO report on labor in digital platforms notes that in Africa, for example, more than 80 per cent of the population derives a livelihood primarily from informal activities.

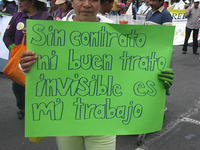

Informal work relations have long been defined in contrast to formal employment – i.e., casual rather than regular jobs, the absence of a written and standard contract, no social benefits or protections, and lack of collective agency and representation. In reality, informal work involves an assortment of activities characterized by diverse employment arrangements. Chen[1] categorizes these as own-account operators who own the means of production, work autonomously, and sell their goods directly to market; own-account workers who are embedded in employment relations disguised as commercial ones; and wage-workers, who are excluded from labor and social protections due to employer evasion. Gender, race, and other structural hierarchies are often reflected in these categories: thus, men tend to dominate own-account work, where incomes are higher and the risk of falling into poverty lower, while women are concentrated in low-income activities.

Platform work reproduces many of these characteristics of informality. Platform workers are readily misclassified as independent contractors, thus lacking access to paid leave, benefits (including maternity benefits), social security, or occupational and health insurance. Yet, they are economically dependent on the platform and have little control over the app. Indeed, as Webster and Masikane[2] show, workers are subject to the app’s “authoritarian algorithmic management,” which assigns tasks, tracks performance, determines pay, and can terminate employment unilaterally.

Location-based work (e.g., delivery) is a primarily young, male activity, characterized by very long working hours and face-to-face contact. Although wages are low, earnings tend to be better than alternatives; and because demand and supply originate locally, it is easier for workers to organize collectively. In contrast, online web-based work (e.g., editing) is undertaken by invisibilized workers in the Global South for clients, most of whom are in the Global North. Characterized by shorter and more flexible working hours, it attracts more women who have to juggle productive and reproductive activities.

Digital platforms, while diverse, are highly concentrated: The 2021 ILO report mentioned above shows that 70% of revenues generated by digital platforms go to the United States and China alone. While this can undermine small and medium enterprises at the national level, it also creates new sources of power. In Gauteng, South Africa, Uber Eats riders are organizing in hybrid collectives, which originated as discrete mutual aid associations along national lines but have evolved into a region-wide network. Connected via WhatsApp, they have developed a repertoire of digital direct action, which includes collectively withholding their labor by logging off. Meanwhile, in Colombia, Rappi delivery workers developed a union app, UNIDAPP, with support from NGOs and the Central Workers’ Union, and have successfully engaged in transnational direct action targeting the multinational platform.[3] In Uganda, the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers’ Union supported developing an app for boda-boda drivers, dramatically expanding its membership and improving couriers’ conditions of work.

While interventions in the informal economy have often centered on enterprise development, ILO Convention 204 highlights the growing consensus that these must also involve the extension of hard-won labor and social protections to informal workers. In the UK, the Supreme Court ruled that Uber drivers are entitled to paid holidays, minimum wages, and pensions. In South Africa, the Competition Commission has launched an inquiry into the impact of platforms on small and medium enterprises.

What of the future?

Two broad pathways can be identified: a deepening of the domination of foreign-owned tech giants with no national or global agreement on how to operate. This will create some informal jobs, but workers will be stuck in low-wage drudgery with none of the protections or benefits of formal employment. With profits and taxes retained abroad, this could be described as a form of recolonization of the Global South.

An alternative pathway could be a “digital social compact” created with the active participation of platform workers and their organizations. This would involve coherent global and national policies, including legislation to protect such workers. This optimistic path opens up the possibility of the extension of labor and social protections to informalized workers.

[1] Chen, M. (2012) “The Informal Economy: Definitions, Theories and Policies.” WIEGO Working Paper, Number 1.

[2] Webster, E and F. Masikane (2020) “‘I just want to survive’: The case of food delivery couriers in Johannesburg. ” Southern Centre for Inequality Studies.

[3] Velez, V. (2020). ‘Not a fairy tale: unicorns and social protection of gig workers in Colombia.’ SCIS Working Paper, Number 7.

Ruth Castel-Branco, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa <Ruth.Castel-Branco@wits.ac.za>

Sarah Cook, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Hannah Dawson, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Edward Webster, University of the Witwatersrand, and past president of ISA Research Committee on Labour Movements (RC44)