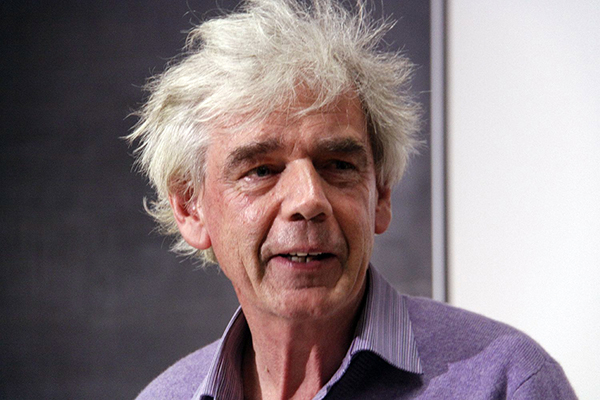

Capitalism, the Uncertain Future of Humanity: An Interview with John Holloway

July 09, 2018

John Holloway is Professor of Sociology at the Autonomous University of Puebla, Mexico. He has published widely on Marxist theory, on the Zapatista movement and on the new forms of anti-capitalist struggle. His book Change the World Without Taking Power (2002, new edition 2010) has been translated into eleven languages and has stirred an international debate. His recent book, Crack Capitalism (2010), takes the argument further by suggesting that the only way in which we can think of revolution today is as the creation, expansion, multiplication, and confluence of cracks in capitalist domination. This interview is part of a project on influential social theory that also aims to explore the intersection of international and national sociology through conversations with prominent sociologists. It was conducted by Labinot Kunushevci, ISA Junior Sociologists Network associate member, who holds an MA in Sociology from the University of Pristina, Kosova.

LK: There are several theories that attempt to analyze and explain the world as a social system and the developments which lead to global inequality. How do you assess the role of Marxism today and what is the future of Marxism and of Marxists?

JH: The only scientific question that is left to us is: How do we get out of here? How do we stop the headlong rush towards human self-destruction? How do we create a society based on the mutual recognition of human dignity? In other words it is not a question of this or that other school of thought. We have to start by saying that we do not have the answers; we do not know how to bring about the social transformation that is so obviously necessary, and think from there. The tradition of Marxist thought does not have the answers either, but it does have the merit of posing the question, the question of revolution. And as for the future, I do not know. But social anger is growing throughout the world and if it does not take a direction oriented towards radical social transformation, then the future is dark indeed. In this sense Marxism (or some sort of revolutionary theory) is crucial for the future of humanity.

LK: According to this article in the , newly unveiled documents reveal that the sugar industry paid and corrupted prestigious Harvard scientists to publish research saying fats, not sugar, were a chief cause of heart disease. How do you explain the corruption of academic consciousness for capitalist benefit?

JH: In a world dominated by money, corruption is built in the functioning of the system, and that includes academic work. But the problem is not just the obvious cases of corruption such as the one you mention, but all those academic and social forces that push us into conformism, that push us into accepting a society that is killing us. Probably almost all of those who read this interview are in some way involved in academic activity, as students or as professors. The challenge we face is to turn that activity against a system that is so obscene, so destructive, in all that we do: in our seminar discussions, in the essays or articles that we write.

LK: I am interested in the question of masculinities associated with different positions of power. Raewyn Connell, in an interview which I conducted with her, said: “It’s important to look at the gender dimension in the actions of people with economic power, as well as people with state power, in order to explain this.” Likewise, Anthony Giddens, in an interview I conducted with him, said: “The global financial crisis – still far from having been fully resolved – reflects some features, even including the gender dimension, given the role that ‘charged masculinity’ played in the aggressive behavior of those playing the world money markets.” What is your view of the role of those playing the world money markets and the relation of masculinity with economic power?

JH: An interesting question. I think I would read those propositions in the opposite direction. The aggressive behavior of those playing the world money markets in the financial crisis did not result from the gender of the actors, but rather the other way around. The aggressive behavior resulted from the nature of money and the constant, relentless drive for its self-expansion. The aggression that is inscribed in the nature of money makes it likely that its most effective, compulsive servants will be masculine, simply because the organization of our society has historically promoted that sort of behavior among men more than among women. As long as money exists, the behavior of those who dedicate their lives to its expansion will be aggressive, whatever their gender. To get rid of the sort of behavior that we identify as masculine aggression, we must get rid of money and establish our social relations on a different, more sensible basis.

LK: How can we create a form of responsible capitalism, in which the creation of wealth reconciled with social needs?

JH: That is impossible. Capital is the negation of wealth creation driven by human needs. Capital is wealth creation driven by the expansion of value, that is, by profit. It is now as clear as can be that that sort of wealth creation is driving us towards self-annihilation.

LK: According to the global World Values Survey by Ronald Inglehart, there are two value systems: the materialist value system and the traditional value system. How do the views expressed in your books Change the World Without Taking Power and Crack Capitalism explain the dynamics of fluctuation between these two value systems and how do these value systems affect the inequality generated by capitalism?

JH: I don’t think it’s a question of finding a balance between value systems. We seem to be trapped in a system that is increasingly violent, increasingly exploitative, increasingly unequal. There is no in-between, there is no gentle capitalism, there is no halfway house. The experience of your close neighbors, the Greeks, makes that very, very clear. The argument of the books you mention is that we have to break with capitalism, but we do not know how to do it, so we must think and experiment. It cannot be done through the state, as your own experience in Yugoslavia and many, many other experiences make clear, so we must find other ways. In Crack Capitalism I explore these other ways in terms of the millions of cracks that already exist in the texture of capitalism, the millions of experiments in creating other ways of living, either out of necessity or as conscious attempts to create another way of living, and I come to the conclusion that the only way in which we can now conceive of revolution is in terms of the creation, expansion, multiplication, and confluence of such cracks.

LK: Do you believe that an egalitarian society is possible?

JH: Yes, but I don’t see that as the principal issue. The central issue is whether we can liberate our activity, our creative power, from the domination of money. Is this possible? I hope so, because I don’t see any other future for humanity. Perhaps you should re-phrase the question and ask: do you believe that it is possible to continue with the present organization of society? To which the answer would be: Probably, but only in the short term, because it is likely that capitalism will not take very long to destroy us. The race is on: can we get rid of capitalism before it gets rid of us? I don’t know the answer, but I do know which side I’m on.

LK: The UK has voted by referendum to leave the EU, while Europe itself is facing many challenges, especially a structural economic and political crisis. These challenges are explained very well by Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Prize winner for Economics, who has said that pressure from the USA, the IMF, and the World Bank has led states to privatize public assets by deindustrialization of economies, and created easily controllable oligarchs. How will this affect other countries inside and outside Europe in the context of the global crisis?

JH: Your last words, “the global crisis” are the important ones. The Zapatistas have been speaking of “the storm” (“la tormenta”) that is already upon us and very likely to get much worse in the coming years. This storm is being felt in all the world: Trump and Brexit are just one aspect of it. How do we deal with this? By turning our anger against capital. And, more immediately, by doing everything possible to reject nationalism. The present growth of nationalism in Europe is frightening. And the lesson of history is clear: nationalism means death and killing, nothing else.

LK: Since Kosova is a small country that became independent only ten years ago, we are still facing many challenges, especially in the process of visa liberalization and EU integration. This isolation is restricting free movement, contact with other European countries and cultures, integration into the European market, and access to European job opportunities, while 60% of our population is under 25 years of age. We feel the need for integration into and belonging the European Union. What would you suggest we do in order for Kosova to integrate into Europe?

JH: Is “belonging to the European Union” the same as “integrating into Europe”? Surely not. The European Union is an authoritarian structure strongly shaped by neoliberalism. It is not surprising that people have reacted against it, but the really frightening part of this rejection is the nationalism that accompanies it (in Brexit, for example). For me the most important aspect of the European Union is that it grew out of a fight against frontiers after the massacre of the Second World War. That is what we must carry on if we are to keep alive the best of European integration: the fight against frontiers. What would that mean for Kosova? Above all, the opening of frontiers to migrants, whether they come from Europe, the Middle East, Africa, or wherever. That is how you can promote contact with other countries and cultures, that is how you can enrich the lives of the 60% of the population who are under 25 years of age.

Labinot Kunushevci <labinotkunushevci@gmail.com>

John Holloway <johnholloway@prodigy.net.mx>