In academic debates, Zimbabwe’s story is contested as much as it is polarized. The nature of the state itself is in doubt and disputed: does Zimbabwe exemplify a fragile, strong and uncooperative, or predatory state? On 15 November 2017, when the military intervened leading to the dethronement of long-time ruler President Robert Mugabe, some characterized the decisive military intervention as a classic “coup d’état.” Yet for others, perhaps long frustrated and keen to see President Mugabe’s departure at all costs, the end justified the means. The latter have preferred to creatively view it as a “military-assisted transition.”

Many would agree that Zimbabwe moved away from the expectations of the hopeful masses and many supporters of the liberation struggle project. Insofar as the liberation struggle ended in the defeat of the white supremacist colonial minority, an historic conquest was won. However, the liberation movement in power has proved to be a disappointment, not only to many well-wishers, but also to the majority of the citizens it now rules. A very promising young state at independence in 1980, Zimbabwe in the post 2000s is now associated with grisly images of violence, cataclysmic economic failure, poverty, and suffering. Several questions beg answers: Why did this happen? How did it happen? Did the ruling elite know their choices would lead to Zimbabwe’s developmental decline?

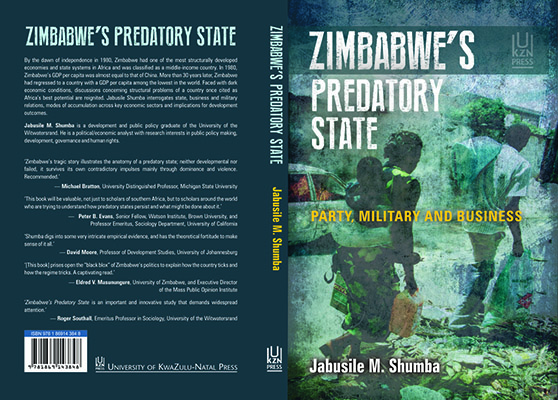

The predatory state

In Zimbabwe’s Predatory State: Party, Military and Business, I argue that the Zimbabwean state is best conceptualized as predatory rather than in any other terms. Yet the notion of the predatory state has remained an elusive concept. I differ with other advocates of the term who have appropriated it to mean the opposite of a developmental state, a special variant of criminalization, or a form of neopatrimonialism. Indeed, most political economy approaches to post-colonial Africa have tended to emphasize the absence of central authority. Ironically, however, the term “predatory” inherently denotes strength – that is, it implies the capacity of predators to prey on their targets, thus requiring the strength to subordinate their victims. For states, such strength arguably rests on the presence rather than the absence of central authority through which the state is able to exercise control.

Based on my empirical research, I suggest that the predatory state is a ruling class anti-developmental accumulation and reproduction project characterized by: (1) party and military dominance in the state; (2) state-business relations shaped by domination and capture; and (3) state-society relations shaped by violence and patronage. However, the distinction between the “authoritarian developmental state” and the predatory state deserves clarification. How do we distinguish between the two in terms of state structure and relationship with society in order to make sense of the structural variations in explaining disparate developmental trajectories?

Predatory states vs. authoritarian developmental states

I argue that both the early version of the authoritarian developmental state and the predatory state are characterized by substantial authoritarian tendencies and the powerful role of personal networks. For example, during South Korea’s high-growth industrialization, Park Chung-hee enjoyed close personal ties with two of the country’s leading businesses, Hyundai and Daewoo; thus, one might find it difficult to disentangle the role of the state-defined public purpose of growth from the role of private profit motives and crony capitalism. However, the state was always in command; it never lost its disciplinary capacity. For instance, when businesses failed to meet set targets, they were punished through withdrawal of incentives. The state’s compulsion was pervasive and real.

The two types of states also differ considerably in terms of the state’s relationship with business and the nature of its relations with the military. The twentieth-century authoritarian developmental state combined the use of disciplinary capacity with incentives to foster productive alliances with business, while predatory state relations with business are parasitic rather than production-oriented; hence they achieve opposite developmental outcomes.

The nature of the relations with the military is also divergent in that the use of the military in the twentieth-century developmental state was oriented towards a national project rather than personal accumulation. For instance, in the Asian classical developmental state model, the military played an effective role in controlling and repressing domestic labor to keep the costs of production low in order to attain industry competitiveness. Under a predatory state, the use of military violence mirrors the personalistic accumulation interests of the power elite.

In terms of the modes of accumulation, the manufacturing sector is conspicuously absent. This points to the rentier nature of the predatory state: that is, it is based on resource extraction rather than manufacturing. The changing structure of the Zimbabwean economy, moving away from a significant manufacturing sector to the post-independence dominance of resource-based extraction, is associated with this predatory shift. The absence of the manufacturing sector has implications that illuminate the deficiency of production strategies, a uniform feature across disparate sectors. In fact, the main aim of policy (such as indigenization and empowerment programs) is to channel rents to members of the ruling elite. Finally, the state needs cooperation with foreign capital (in this case, Chinese and South African) to generate foreign exchange and tax revenue to support essential government functions. Therefore, friendly foreign capital is allowed to participate in the sharing of resource rents.

The key conclusion of the study is not only that the power elite had class interests that inhibited economic transformation and development, but also that its voracious modes of accumulation and political reproduction transformed and sustained Zimbabwe’s predatory state. The implications of this will be far-reaching. Over the years, the country’s developmental capacities have been undercut by a predatory elite which relied on violence and patronage to retain power and accumulate wealth. Reform will come at a political cost as it undermines the deeply embedded patronage networks. In the aftermath of the November 2017 overt military intervention, the party-military and business complex has been rejuvenated and is likely to endure in the years to come.

Jabusile Madyazvimbishi Shumba, Africa University, Zimbabwe <jabusile_shumba@biari.brown.edu>