Turkey's Rebellion: Gezi Park, The Art of Resistance

October 25, 2013

“To live like a tree single and at liberty and brotherly like the trees of a forest, this yearning is ours.”

(Nazim Hikmet)

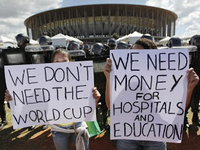

It is very hard to express our feelings about the last two months of resistance, June and July of 2013, which were unique and inspiring not only for Turkey but all over the world. “Everywhere is Taksim; Everywhere is resistance” became a famous slogan, stated in many languages and occasions. Many people with environmental and urban consciences gathered to protest the urban demolition of Gezi Park next to Taksim Square, İstanbul. However, no one was thinking that defending “two or three trees” would lead to a broad movement for emancipation and dignity.

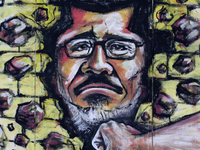

Still, it is difficult to claim that this movement was simply a reaction against the destruction of the park. Rather it was provoked by statements of the Prime Minister concerning the private lives of young people and women and restrictions of freedom of expression and human rights. It was a protest against new regulations, passed overnight without discussion and consultation, that displaced residents from city centers and shanty towns (gecekondu), from social housing and old neighborhoods. This type of official discourse continued during these two months, leading to a massive involvement of common people that was deepened by police interventions, turning the protests into battlefields. The government prohibited May 1st celebrations in 2013, which had been planned for Taksim Square, on the grounds of the ongoing projects there. It brutally attacked people who were protesting against the closure of the Emek Movie Theater that was to be replaced by a shopping mall, which was also the fate of the Atatürk Cultural Center and Muammer Karaca theater, even though Istanbul had been awarded the distinction of being the European Capital of Culture in 2010. The government took the offensive against all aspects of art – actors, budgets, costumes and mise-en-scène of plays and performances.

Claiming an urban commons against the many forms of enclosures, professional groups and associations, political platforms, neighborhood associations came together under the banner of Taksim Solidarity that had been struggling for years with urban-related problems. During these days, different leftist, socialist, Kurdish, anarchist, and LGBT groups, Kemalist people, and more broadly common people from different classes and generations but especially young people from the “X/Y generation,” all walked together full of emotions and conviviality.

Gezi Park became an incandescent light for the right to city, the right to use and access the city center, the right to participate in decision-making about the production of space, the right to self-realization by making the city a work of art. One of the main resistance-related terms was çapulcu, a word Prime Minister Erdoğan used in referring to the protesters as “looters.” The word was reappropriated by the demonstrators and given positive connotations, meaning people who were proud to be fighting for their rights, for their dignity as human beings, resisting all forms of oppression. This civil resistance has gone beyond party politics to become the site of collective performance and language, exiting closed halls for “solidarity forums” of neighborhood parks in cities across the country.

In such an environment, where so-called “information channels” only offer ideology, political art sprung up, gaining its strength from a creative humor, circulating in the social media, which surprised the structures of power and challenged their political traditions and repertories. During these warlike but carnivalesque days, imagination, art, and humor produced new slogans of hope, outside conventional tropes, written on the walls of the re-appropriated and reclaimed streets.

The wide range of images, popular characters, words and cultural elements reflected the gathering of different groups, but all making the same democratic demands. The “unbalanced intelligence” of the humorous cultural repertoire of the 80s and 90s generations, usually accused of being apolitical, artfully resisted the “unbalanced violence of the police,” which caused six deaths, hundreds of injured, and fifteen people who lost their eyes. Protestors sung the lyrics of Çapulcu marches composed by themselves. Leading actors of popular TV series, such as Muhteşem Yüzyıl and Behzat Ç., became “popular figures” in the resistance. Not only from Turkey but from all over the world, artists like Patti Smith, Joan Baez, and Roger Waters have supported the protest with their photos, videos, and concerts. Plays on words became slogans of the movement: from popular movies (“V for Vendetta” has turned into “V for Mrs. Vildan,” describing housewives who participate in the resistance; the expression “Daytime Clark Kent, Nightfall Superman” signified white-collar workers participating in the resistance after work) to singers (“Justin Bieber” turned into “Just in Biber/Pepper” which refers to excessive use of pepper gas by the police), songs ( “Everyday I’m shuffling” turned into “Everyday I’m çapuling”), and football and commercial slogans (“Nokia connecting people” turned into “Fascism connecting people”).

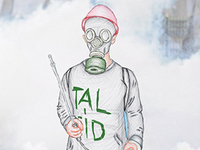

The façade of Atatürk Cultural Center in Taksim Square was made the “common face” of the resistance as it was in the legendary pictures of May 1st celebrations. There were also other artistic creations in the Park, including theater, different forms of dance performances, film, and music. The most significant mascot of the resistance, commonly used in drawings on the walls, was the “penguin” which referred to the documentary on the CNN-Turk television channel that was broadcast at the very time of the violent police assaults. The Standing Man (“duranadam”), who stood still and silent for eight hours during the protests was one of the Gezi Park heroes, like the Talcid Man (Talcid is a medication for the stomach to diminish the effects of pepper gas) or the Woman in Red (the woman who faced the pepper spray in the early days). They were made into collective symbols through graphics displayed on Facebook. The Standing Man – who was actually the choreographer Erdem Gündüz – stood in front of Atatürk Cultural Center and initiated a new type of resistance, just by “standing.” Others would studiously read books in front of the police. Another important type of resistance, again a satirical play on the Prime Minister’s words, this time after he referred to the movement as “pots and pans, always the same noise”, led to making noise with pots and pans from balconies across the city. When the climate became calmer, protesters started to paint the stairs in the streets with the colors of the rainbow.

In short, the protests in Taksim Square and Gezi Park represented a new politicization, a collective memory and language beyond conventional politics. As scholars have underlined, but many politicians have denied, urban space has the potential to reveal its “spatial” injustices obscured in “politics as usual.” Revealing social divisions, art produces a universal unity by impressing scenes into the depths of our consciousness. The collective art of çapulcu, now known in as “chapulling,” may be erased from the walls of the streets, but it will not be so easy to eradicate it from the hearts and minds of the witnesses and participants of Gezi resistance. Though it is no compensation for the loss of the murdered people, Ethem Sarısülük, Abdullah Cömert, Mehmet Ayvalıtaş, Medeni Yıldırım, Ali İsmail Korkmaz, and Ahmet Atakan, we end with the optimistic slogan painted on street walls: “Nothing will be the same again, wipe away your tears”.

Zeynep Baykal, Middle East Technical University,Turkey and ISA Member of Research Committee on Racism, Nationalism and Ethnic Relations (RC05)

Nezihe Başak Ergin, Middle East Technical University, Turkey and ISA Member of Research Committees on Regional and Urban Development (RC21) and Social Classes and Social Movements (RC47)