Islamic Conservatism has now come to power in Turkey, not once but three times, each time increasing its support. It has taken a political route that extends from political power to social and even cultural domination. It tries to remove the tutelage of the Turkish army, and, through economic and political reform, it tries to open such gridlocks as the Kurdish issue and the headscarf issue. It creates the European Union as an ideal, and with its psycho-economic administration it makes Turkey hospitable to international markets and effective in foreign affairs within its region.

Over time, the regime has acquired the support of the majority and this now motivates it to design social life in its own image. The political influence of the Turkish army has, indeed, diminished but the police force has been strengthened, which is now increasingly perceived as an organization working only for the benefit of the government. The academy and media have been censored (or self-censored). A bizarre “great man” discourse and “gentleman”[1] politics have been routinized.

Still, discontent was mounting, marked by the unspoken anger of the victims of urban transformation, the oppressive use of subcontracting, and the absence of material improvements for the majority despite the supposed strengthening of the economy. Hunger strikes in prisons demand the possibility of conducting legal defense in one’s mother tongue. Closing Taksim Square to May Day celebrations with bogus excuses angers many, as does the construction of a third bridge in Istanbul which will be named after Yavuz Sultan Selim, the Ottoman Sultan who massacred a great number of Alevis. Then, there are also matters the government does not want to take up, such as the ubiquity of violence, tortures, rapes directed towards Kurdish children in Pozantı Prison, and the Roboski/Uludere massacre of Kurdish villagers in 2011 and the May 2013 “terrorist” bombings in Reyhanlı.

The Gezi Park incidents began as a mere protest. However, for the Prime Minister this protest was an ideological provocation engineered by both internal and external conspiracies. Through his excessive desire for power and his unwillingness to make the compromises that democracy requires, the Prime Minister effectively turned the streets into an extension of his politics. The escalation of conflict that began on May 31could have been avoided if the Prime Minister had not accused people of being “looters” and “servants of special interests.” Arriving at an agreement would have been much easier had he not constantly wagged his finger at the protestors, declaring them to be a public enemy, and had protestors not been killed by the police.

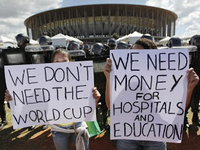

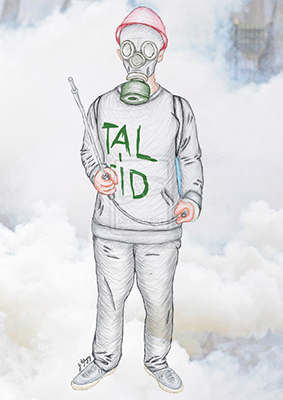

On June 1 people swept through police barricades en masse, entered Gezi Park and from there made their voice heard all over the world. The police retreated and left the park, which then became a festival for anyone to air their grievances. A new culture of resistance arose with its sense of humor, its graffiti, and the widespread use of social media. The feminist and LBGT movements were particularly prominent, exposing sexist discourses with slogans such as “do not swear at women, gays, prostitutes” or “resist obstinately, but not with cussing.”

On Saturday, June 15 the Prime Minister held a public demonstration in Ankara, supposedly to reveal the “special interests” and subversive forces at work behind the Gezi incidents. He said that the following day there would be a public demonstration in Istanbul and so Gezi Park would have to be evacuated immediately. The resulting police assault, using gas bombs, water cannons, and truncheons, turned into a fiasco. It being a weekend the park was like a fairground, full of kids, seniors and disabled, who were all bewildered by this sudden invasion of gas bombs. True to his word, the next day, the Prime Minister did arrive to a purged Istanbul to hold his public demonstration, unconcerned that the hospitals were full of wounded, injured, and even dead people while many activists were in custody.

Resistance has continued. People gather at Gezi Park and other parks to organize forums to discuss government politics and the future of the city. They are creating their own language, their own culture, and their own urban consciousness. The social movement has demanded that the government protect ethnic communities and that it conceive of society in terms of its plurality rather than simply in majoritarian terms. It demands unrestricted rights to freedom of expression and association.

As the actions in Gezi Park developed from protest to riot and, now, from riot to resistance they have turned into a most influential social movement, calling for the replacement of personal rule with a more thorough institutionalization of democracy. Along with the Gezi demands, the protestors call attention to the Kurdish problem. Everyone is watching how the government will approach these issues, and whether it is capable of changing its path.

[1] The phrase of “gentleman” is an adjective commonly used for Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and this phrase implies a “one man” administration.

Polat Alpman, Ankara University, Turkey