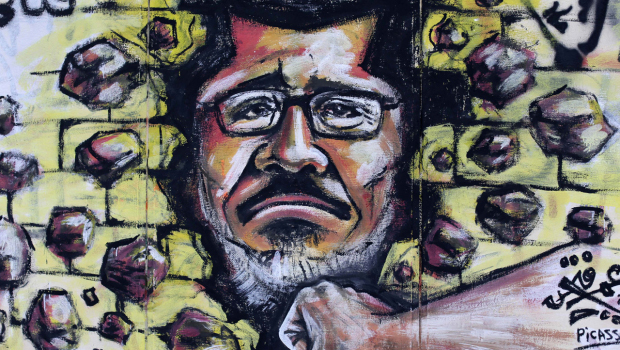

The release of ex-president Hosni Mubarak from prison on August 22, 2013 represents a turning point; it marks a counter-revolutionary restitution that had begun probably the day after Mubarak’s resignation on February 11, 2011, but culminated on July 3, 2013 when General el-Sisi forcefully ousted the elected President Mohamed Morsi, the man of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood. The military annulled the constitution and installed an interim civilian government to undertake new elections for a new president, parliament, and constitution. In a violent crackdown that left more than 1000 (including 100 police) dead, the generals began to quell the defiant Muslim Brothers. With the Muslim Brothers in retreat and the “liberal-secular” opposition in disarray, the Mubarakists rejoiced in ecstasy and went on offensive in the media, in the streets, and in state institutions. An orgy of national chauvinism, misinformation, and self-indulgence fed their fantasy of restoring the ancien régime. The old guard – the security captains, intelligence bosses, big businessmen, and media chiefs gained fresh blood. Soon, surveillance began to extend from the Brothers to hunt any known figure deemed defying the new rule – including left, liberal, and revolutionary. Even Mohamed El-Baradei, the ex-vice president of the new government was not spared. Stunned, the revolutionaries (those dispersed constituencies who initiated and carried through the uprising of January 25, 2011 for the cause of “bread, freedom, and social justice”) watched the counter-revolution march on.

How could this turn-around happen after over two years of incessant revolutionary struggle? If revolutions are about profound change, then all revolutions carry within them the germs of counter-revolution waiting for a chance to strike; but they rarely succeed, primarily because they lack wide popular support. The infamous 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte did not last long, and the French Revolution reasserted itself. The 1848 revolutions in Europe overcame the wave of formidable counter-revolutions as the new democracies defeated the old orders in the course of two decades. In the 20th century, the internal intrigues and international wars against the revolutions in Russia, China, Cuba, and Iran all failed, even though they rendered these revolutions deeply security-conscious and repressive. In the Philippines, the military’s consecutive coup attempts against Cory Aquino’s government, following the anti-Marcos “People’s Revolution” in 1986, were all neutralized. Only in Nicaragua, a rare experience of democratic polity after the 1979 revolution, the counter-revolution succeeded through the electoral means; the US-backed Contra-war severely undermined the revolutionary Sandinista government, thus ensuring the electoral victory of the rightist Violeta Chamorro in 1990.

But in Egypt the turn of events was not terribly far-fetched. Egypt, Tunisia, and Yemen, as I have suggested elsewhere,[1] did not experience revolutions in the 20th century sense of rapid and radical overhaul of the state; rather, they experienced “refo-lutions”, or revolutions that wanted to push for reforms in and through the institutions of the incumbent states. In this paradoxical trajectory, revolutionaries enjoyed massive popular support, but lacked administrative power; they earned remarkable hegemony, but did not actually rule, with the consequence that they had to rely on the institutions of the incumbent states (for instance, the ministries, the judiciary, the military) to change things. Of course it was naive to expect such institutions with deep-rooted vested interests to alter, let alone undo, themselves. If anything, they remained defiant waiting for a chance to counter-attack. Revolutionaries quickly realized their handicap, but could do little beyond leading otherwise heroic street protests; for they lacked a solid and coherent organization, a powerful leadership, let alone the coercive power to deploy when necessary.

Thus, while non-Islamist revolutionaries were rapidly marginalized, the highly-organized Muslim Brothers succeeded, even if with a slim majority, to form a government by election. But they failed to fulfill the revolution’s demand for “bread, freedom, and social justice.” If anything, they focused on consolidating their own power even if this meant compromising with the institutions of the “deep state,” such as the police and intelligent apparatus, which in fact needed a major overhaul. They deployed religion to justify rule, fantasized to “Islamize” the state, continued with the neoliberal economy, and showed a remarkable inability in governance. Already despised by the sizeable Mubarak supporters, the Brotherhood began rapidly to lose the sympathy of many ordinary people who had supported Morsi’s presidency. By the end of his first year, president Morsi and his patrons were deemed an obstacle to deepening the revolution. Thus, opposition to the Brotherhood’s rule in practice “allied” the anti-Mubarak revolutionaries with the counter-revolutionary Mubarakists, which together with millions of disenchanted ordinary Egyptians created the June 30th rebellion. The tamarrod (rebellion) movement served as a catalyst to mediate the “alliance” of these strange bedfellows. Its activists worked day and night for months prior to June 30th to mobilize dissent gathering, they claimed, some 22 million signatures of no-confidence in order to dismiss president Morsi.

Watching the immense dissent without a powerful unified leadership, the military encouraged and jumped on the wave to lead its sprawl, inserting itself as the leader of the “anti-Morsi revolution.” Many Egyptians, at the time, saw the military’s intervention as a necessary “revolutionary coercion” to remove the key barrier, i.e. the Brotherhood rule, which they deemed had stalled the revolution. But they could hardly imagine what the generals and their counter-revolutionary partners would do after July 3. The reports of the military and counter-revolutionary circles supporting the tamarrod with the intent of banishing Morsi should not obscure the genuine widespread dissent that the Brothers’ rule had already instigated. There is a difference between whatever the tamarrod leaders had in mind, and the popular idea of tamarrod that had captured the imagination of millions of ordinary Egyptians before the June 30th rebellion. In one of my random conversations with the people on the streets, I talked to a man, the father of four children and a mechanic for tourist boats, who had left his family behind in the southern city of Aswan to come to Cairo for work because he had lost his job. Angry at Morsi, he said that the Brothers didn’t “have the mind to run the country”; “they say tourism is haram [not allowed], or that foreigners should return home.” The Brothers, he went on, “are terrible; but this June 30, it will be their end; people will go out to topple them.” He stated this on June 9, three weeks before June 30. The Brothers were, indeed, toppled, but the military and counter-revolution emerged triumphant.

The military’s move targeted not just the Muslim Brothers, but also the revolution per se. Like the Mubarakist old guard, they never came to terms with the very idea of revolution – the idea that Egypt had changed; that new actors, sentiments, and ways of doing things had emerged, and that these would be likely to disturb the established hierarchies – rulers vs ruled, rich vs poor, sheikhs vs lay people, men vs women, old vs young, or teachers vs students. To reassert its rule, the old guard has already intensified nationalist sentiments, but it will not hesitate to bring in conservative religiosity (even of Salafi type) along with economic neoliberalism, and redeploy its ideological trinity – Morals, Market, and Militarism.

Could this have been avoided given that the counter-revolution was determined to strike back? If the Muslim Brothers were genuinely inclusive, and were prepared to work with the non-Islamist opposition in a revolutionary coalition, and if the non-Islamist opposition were prepared to acknowledge the elected Islamists, even though illiberal, as a partner in a broad representative polity, things might have turned out differently. Indeed, a possible balance of forces between the elected Islamists, non-Islamist opposition, and the subdued old guard could by default have generated a space for debate on such issues as citizenship, civil liberties, and rights and responsibilities – a space in which parties could have learned through practice how to play the rules of democratic game. Of course, such polity would have been unlikely to address the powerful claims for social justice, but the subaltern classes would have had a greater opportunity for mobilization than they do have under the counter-revolution.

This sounds like an abstract speculation, but it does have direct bearing on Tunisia. The ruling al-Nahda in Tunisia would serve its own interests if it were more inclusive in its workings with the secular opposition, acknowledging their concerns for civil and individual rights. And the secular forces which opposed Ben Ali would secure their new freedom if they would acknowledge the al-Nahda religious party as a player, and even a partner, in the Tunisian public sphere. A populist counter-revolution, if it succeeds, could wipe out not only political Islam, but also the secular intelligentsia that has just recovered from “political death” under Ben Ali’s police state.

[1] Bayat, A. (2013) “Revolution in Bad Times.” New Left Review 80: 47-60.

Asef Bayat, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, USA