Read more about Open Section

Water Struggles as Resistance to Neoliberal Capitalism

by Madelaine Moore

November 21, 2023

One of the most prominent words over the last decade has been “fear.” Here I refer to the multidimensionality of fear: of urban violence; of our bodies being violated; of state violence; of social injustice; of the future; and even existential fear. Reactivity combined with the survival instinct of living under the imminence of a global collapse has made fear a compass for political behavior and the constitution of social bonds. What I will call the “politics of fear” includes aspects that go beyond its recent emergence (notably expressed in the global rise of the far right and its instrumentalization of fear). A comprehensive perspective suggests we are witnessing the agency of far-right political groups – as is the case with Bolsonarism in Brazil, which I have studied – but also societal tendencies that accommodate the authoritarian political imagination and the socio-historical-existential anchors of fear.

Between the visible and the invisible

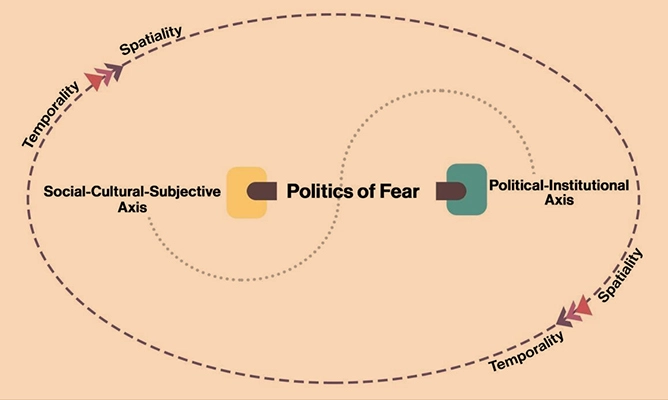

A perspective that does not reject movement, folds, and entanglements of multifaceted elements, but explores the multiplicity of what is reiterated, experienced, and accumulated not only on a mental level but also in muscles, blood, and impulses is what I claim as the practice of fissures. Graphically, the politics of fear is malleable to the fluidity. Separations are merely didactic and analytical, and there are porosities between elements. It is worth noting that not even institutions, individuals, collectives, and companies are cohesive and unidirectional actors. The politics of fear is constitutive of modern politics and, in a broader definition, signifies the set of mechanisms that mediate the transformation of fear – whether produced or mobilized – into an impetus for social cohesion.

The pervasiveness of fear is a political affect which is a dynamic vector in the constitution of social bonds, while it also legitimizes social exclusions and animosities. The apparent oxymoron of the politics of fear is entangled in temporal and spatial amalgams. By this, I mean memory; aesthetics; architecture; militarized urban planning, infrastructures, and their social abysses; processes of digitization and the acceleration of time; the experience of borders and the geolocation of fear; and colonial and urban violence, among other aspects.

The experience of fear differs according to geometries of power, primarily involving race, gender, and class (which constitute the matrix of fear and social enemies). For example, in territories where violence particularly emanates from the state through the police, such as in the Brazilian favelas, the fear of uniformed agents is significantly greater than in the city, where the military often inspires a sense of security.

Within the fissures of the politics of fear, there are two axes: political-institutional and socio-cultural-subjective. The former deals with the underlying colonial relationship between the state and civility based on the order/chaos binary. It is central to the notion of the monopoly of violence and the state’s responsibility for social protection; it underpins the logic of what is acceptable/legitimate as authority; it constitutes the mirroring of notions of morality and secularity and the entrepreneurship of politics. Closely related and within the same spatial and temporal flow, the socio-cultural-subjective dimension consists of the cognitive basis and political implications of affirming certain rationality: the logic of dangerous otherness (which creates the need for a state that protects), with effects related to the politics of enmity and angry political polarization; the implementation of surveillance technologies in digitization processes and a certain willingness to curtail freedom; the aesthetic production of fear and images of violence with high media reproducibility.

The conceptual outline of the politics of fear allows reflection on the rise of the far right and popular adherence to authoritarianism from a comprehensive perspective. The approach is concerned with the emergence and persistence over time of the far right, oscillations either in its radicalism or adherence, and thus understanding its consequences as socio-political landmarks beyond surprising electoral victories around the world. Reflection on how public life and political experience produce and mobilize affects will serve as support for social adherence. Inspired by Kathya Araujo, I have previously identified fundamental socio-existential anchors that are key for understanding the appeal of far-right ideas in contemporary times.

Authoritarian socio-existential anchors

The relationship between authority and perceptions of efficiency that is cemented in the collective imagination of territories with colonial state formations is fundamental for the assimilation of authoritarianism. There is a historical dynamic of criminalizing otherness reflected in the racialized structure of the state, the use of force and violence as territorial domination, and subjective markers of distinction between colonizer and colonized. When we look at Brazil, it is remarkable how its historical formation demonstrates the construction of this understanding of the effectiveness of authority based on the repression of enslaved rebellions. Recognizing that this widespread fear is foundational and sustains social relations allows us to think of variations in the ways authority (authoritarianism) is exercised, even under the guise of democracy. The compatibility of authoritarianism with neoliberalism demonstrates, moreover, the pervasive expansion of authoritarian practices, manifested in multiple spheres of life, from the most intimate and individual to broader social relations.

The role of fear in the process of constituting images of self and others, as well as in the dynamics of territoriality in the emergence of urban spaces, justifies the idea that fear is a colonizing affect that updates divisions in the city, as originally formulated by Vladimir Safatle. Territories offer a prism through which social arrangements can be identified. There are forceful implications in both directions between fear and spatiality, which include architecture, urban planning, and the representation (and location) of subaltern groups as “bearers” of threat and violence. Some of the consequences of this spatiality can be seen in walled cities, in gated communities, or in militarized urban planning. The existence of the metropolis is not visible in itself: it requires the colony for the contrast between the invisible and the visible to be revealed, and it is from this perspective that the process of urbanization is understood as geographies of fear and the criminalization of dangerous otherness based on racism.

Urban sociology in countries on the world’s periphery suggests that there is an extrapolation of the feeling of insecurity through media and daily conversations among people, as well as the actual presence of crime. Following the aesthetics of militarized urban planning, fences and walls are intensified, organizing the city not only for reasons of security and segregation but also for those of aesthetics and status. This leads us to reflect on the importance of maintaining and deepening social inequalities and mediatized urban violence for the consolidation of social chasms.

Another crucial anchorage that justifies the Manichean foundation of good (us) and evil (them) concerns relationships of morality, religiosity, and rationality. The result of these fusions – involving religion, the state, and rationality – refers not only to the character of norms and institutions; they are elements that trigger collective interpellations and the production of shared sensitivities. At this historical moment, when we are already quite familiar with a positive connotation of “civilization” and “domestication,” we can say that women and colonized and enslaved populations continue to be more immediate targets (the ‘deviants’) of patriarchy. It is no wonder that the reactivity of the far right is characterized as masculinized, white, claiming heteronormative virility and militarized violence, encompassing its repulsion of what they call “gender ideology.” It is true that the displacement of women from the restriction of domestic space to occupying public spaces has stirred an existential fear within masculinity.

Authoritarian imagination and societal tendencies

Furthermore, it is worth highlighting three contemporary societal tendencies that constitute socio-existential anchors accommodating the rise of the authoritarian imagination: individualization, digitization, and a sense of urgency. The first deals with the modern subject tutored by the terror of the stranger. Encounters with the other destabilize the order of self. The individual lives in a world that is disturbing and so continually seeks artifices as a protection from the other who is seen as an intruder, an announced danger. In this sense, social bonds are governed by fear – economically structured – where the authority of the state guarantees that life in society is not a threatening vulnerability. The mark of individualization, in its radicalized expression, can be exemplified through “entrepreneurship of the self.”

The second tendency, digitization, deals with the power of image penetration, which is increasing in a reality where the acceleration of time is a fundamental characteristic. Digitization sustains – and is sustained by – a high flow of information, technological advancements with implications for communication and relations, scattered attention in the short-term accommodating multiple possibilities, and thus the instantaneous power of the image. The image has “symbolic efficacy,” meaning that it already carries content and immediately produces meaning in relation to the signifiers that make up the imaginary unity of the self. The centrality of the image, intertwined with the digitization of society, has significant effects on language itself and the circulation of ideas. The concatenation of images that produce an authoritarian, racist, masculine repertoire is integrated, through various means, into the imaginary that the far-right claims and amplifies.

Finally, in contemporary capitalism, we live in the paradox of technological development with a proportional acceleration of time which leads to a continuous state of urgency due to a lack of time. What seemed to point to an exuberant economy of time, given the increased speed of transportation, communication, and especially production, has turned into its exhaustion. The acceleration of modernity implies a social desynchronization, where individuals always perceive themselves as being late and are afraid of missing out on opportunities. This sense of delay promotes two strategies that seem central to the far right. The first is the notion that everything is an “ultimatum”: “we must act, and we must act now,” there is no time for the elaboration of a future project. The second indicates the obsolescence of institutions and their apparatus which prove slow in the face of the rapidity of flowing needs. These dimensions arise from the dynamic of time acceleration reflected by Helmut Rosa, which impacts collective and individual understanding of space-time. If operating in a sense of urgency is imposed despite individual desires, through social structures, then we can say that there are means of agency in this.

Final notes

Fear has produced and shaped subjectivities throughout history by influencing discursive matrices (languages) in an insomniac and mobile relationship with sensitivity and corporeality. Structural and structuring elements of fear are present in history, constantly reinventing themselves and reorganizing interpersonal relations. Devices and anchors of the policy of fear are mobilized as justification for authoritarian practices, whether in interpersonal relationships, groups, or between society and the state. The dispersion and multidimensionality of fear are striking, revealing a social aspect that is difficult to isolate; there are visible and invisible layers, which are related to fear in a mutually sustaining movement. The deepening of the multiplicity of fear devices as a political affect has led to the realization that they are agency and instrumentalization for strategies of domination and social control, which influence forms of interaction and subjective constitutions.

Lara Gonçalves Sartorio, IESP-UERJ, Rio de Janeiro State University, Brazil <larasartorio@iesp.uerj.br>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: