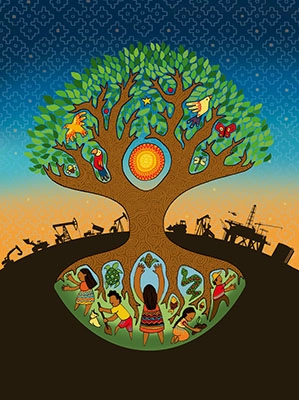

From a socio-environmental justice perspective and within the universe of popular environmentalism, we defend a just and popular energy transition that is based on an anti-capitalist and socio-ecological narrative. However, to achieve this, we must first make a diagnosis of the current situation and establish the path towards a desired future. In this regard, it is important to understand the magnitude of the changes needed to address the problems associated with energy. This implies considering not only greenhouse gas emissions, but also social inequalities and socio-environmental impacts in the territories, as well as conflicts associated with energy and the concentration of energy power in a few hands and with large corporations.

We understand the energy system as a set of social relationships that bind us as a society and in our society–Nature relationships, which are determined by production relationships. The just and popular energy transition requires decommodifying, democratising, defossilising, deconcentrating, decentralising and depatriarchalising. But what actions and processes are necessary to achieve that?

The path of decommodification and democratisation

The just and popular energy transition is based on the premise that all people have a right to energy, and challenges the idea that energy is a commodity. It is about deprivatising and strengthening the various forms of the public, the participatory and the democratic. One of the slogans is to decommodify, which implies freeing energy from the predominance of the commercialised logic of economic benefit and focusing it instead on the ability to control and reproduce life in all its dimensions, both material and symbolic.

We consider energy as part of the commons, and therefore, as a collective right in congruence with the rights of Nature. It is necessary to build a vision of energy as a right, taking the struggles for the right to water as an example. This right is not only for human beings, but for all living beings. We incorporate Nature and all its species into this definition, because we recognise that there is an interdependence between the full enjoyment of human life and the environment.

Within the framework of the current capitalist system, markets are instruments that serve sectors whose rationale is based on unlimited capital accumulation, beyond the physical limits of life. The concept of decommodification challenges the centrality of capitalist markets to solve certain needs. The recovery of the public is essential to this path. It not only implies a debate about ownership by reclaiming it from private hands, but also about management. In our perspective, recovering the public should not be limited to its association with the state (national). It is a question of strengthening and recreating all forms of the public, in terms of ownership and management, including historical experiences relating to the community, communal, municipal, collaborative and cooperative areas. These are valuable tools that must be strengthened in the face of the supposed superior efficiency that private companies offer in the provision of services.

Decommodifying and socially constructing the right to energy implies, among other tasks, a broad legislative, regulatory and normative reform that repeals privatisation laws and the liberalisation of markets that have placed the private sector at the centre of the energy system. It is also key to advance a de-privatisation process that includes not only energy companies but also other basic services, as well as developing tools that strengthen all forms of the public in terms of ownership and management, with emphasis on different levels and spheres (cooperative, community, state and national). It is necessary to strengthen the required institutional framework to achieve this.

As a first step towards a process of democratisation of the sector, it is necessary to establish information mechanisms that allow the participation of any community to be involved in decision-making, whether urban or rural. To do so, it is important to review, correct and even, on some occasions, reverse the direct subsidy policies for fossil fuels and various sectors of the fossil-based economy. It is also crucial to recognise and support institutions and actors involved in the generation, distribution, management and consumption of energy outside the capitalist market.

Furthermore, it is important to assume the possibility of deciding on energy at the local level, in its different dimensions (generation, consumption, energy poverty, etc.). Municipal energy agencies and experiences of reclaiming public services are examples that could be strengthened. To make this process more dynamic, it is also necessary to advance methodologically: developing tools and procedures for constructing local, community and municipal energy policies as a form of collective appropriation of these policies.

It is not just about decarbonising

Carbon sinks, which are the mechanisms that absorb greenhouse gas emissions, and the finite availability of materials and minerals set a limit on the ability to substitute fossil fuels with renewable sources, within the framework of the current production and consumption matrix. This means that it is essential to reduce the net use of energy as the main goal, although this reduction must be planned and executed while taking into account the need to balance existing inequalities and the needs of different countries and social groups.

It is also important to consider that it is not enough to merely advance in the use of renewable energy sources. Rather, it is necessary to consider the environmental, social and political dimensions of each specific venture to determine its sustainability.

Among the actions that can be taken to face these challenges, the following stand out:

- agree not to exploit unconventional and conventional hydrocarbons in risk-prone areas, such as offshore zones, or reduce their use within the framework of a plan to abandon fossil fuels in the short term;

- monitor the net decrease in energy use beyond the climate commitments made;

- have specific proposals for different sectors, such as transportation, which in Latin America is the main energy consumer and should be considered as an energy sector in and of itself;

- develop tools that visualise the socio-economic benefits of energy efficiency and establish regulatory changes that go against commercial logic;

- stop adopting renewable energy competitive bidding processes between large commercial/transnational providers as the only option and prioritise instead the decentralised and deconcentrated development of these sources.

On the production model and consumption

To move towards a just and popular energy transition, it is necessary to build a production model that is compatible with the sustainability of life and the care of the ecological systems and cycles that make it possible. It is essential, as feminists propose, to put life at the centre of this model.

The energy transition that we propose requires recognising the natural and human physical limits, as well as the immanence and importance of links and relationships as inherent features of the existence of life. These conceptions are associated with new ways of organising life in society, new forms of production, revaluation of the place occupied by productive and reproductive work in societies, and new forms of consumption, associated with a change in the society–Nature metabolism.

Regardless of the initiatives associated with energy efficiency in various sectors, it is necessary to advance in sectoral analyses to question the regional production and transportation matrix and seek sustainable and fair alternatives. Concrete proposals in this area include, for example:

- establish maximum circuits for the circulation of goods and develop short production chains that prioritise local products;

- analyse the areas of material production that need to degrow and determine what to stop producing; analyse how to enhance services over material goods. This must be accompanied by establishing timelines for this degrowth;

- develop new areas of production and less energy-intensive services;

- establish timelines to stop using individual internal combustion vehicles;

- implement a process of modal change in freight transport;

- rethink the role and design of infrastructure, since it is financed with public funds and determines future behaviour and consumption.

Similarly, a process must be undertaken that allows us to advance in the social construction of other forms of satisfying human needs. It is an intense and extensive process, but one that can be streamlined through the use of various tools, for example, strengthening urban networks for sustainable consumption; developing regulations that prohibit planned obsolescence; making mass life cycle analyses of products; prohibiting or restricting advertising on particular branches of products; establishing a rapid program to eliminate energy poverty; associating energy policies with habitat policies; and restricting luxury uses of energy.

Tatiana Roa Avendaño, Vice-Minister of Environmental Planning of the Territory, Colombia <troaa@censat.org>

Pablo Bertinat, Taller Ecologista, Argentina <pablobertinat@gmail.com> / Twitter: @tatianaroaa and @PactoSur