The term “transformation” has a short yet diverse history. It ranges from everyday to political-scientific descriptions of all kinds of change, from political regime change and the development of post-colonial orders into liberal democratic capitalisms, to the different varieties of a globalizing capitalism and finally, even more broadly, to the “Great Transformations” of the human-nature relationship, of the state-socialist orders into capitalist ones and beyond. While often focused on the controversy about how and with whom different actors could get from “here” to “there,” transformation narratives have often in a rather curious way neglected certain aspects of a “politics of the future.”

“The future is already here; it is just not yet distributed evenly.” That is what William Gibson, who invented the term “cyberspace,” is said to have stated a quarter of a century ago. However, he kept silent about the current or future distribution of this future – even though the question already pressed to the fore centuries ago. The emergence of modern relations of time in bourgeois modernism not only revolutionized the hitherto valid distinction between past, present, and future and changed the meaning of “future” from passive to active (“the future is made”), it also moved profit-making and calculation with coming time – that is, futures – into the center of the new economic system. Ultimately, the pre-capitalist societies focusing on the past were transformed into capital-accumulating societies focusing on the future. It is also since then that strategic projects aiming to broadly land grab the “continent of the future” have existed.

Through the universalization of markets and capitalized money and their territorial as well as social “disembedding” (Karl Polanyi), what came into being were such strategic formats as the “present futures” (Niklas Luhmann) that now exist always and everywhere. Today these are, for example, the global bets on the future of the dominant money-power complex of the financial industry, the promises of security and the expansion of the “future apparatuses” of the preventive, violent, and military state or the calculations made on ecological sustainability and economic profit through the transformative coupling of geoengineering and a post-fossil fuel “green capitalism.” More than anything else, the construction of a complex arrangement of technological-social innovation through the so-called Industry 4.0, big data, the digital society, smart spaces, and digital dominance signifies the great promise of a global consolidation into a project for the transformation of the informational-industrial productive forces of contemporary capitalism.

There is much to suggest that this will once again revolutionize the large bundle of time-related individual and socio-cultural behavior patterns as well as social practices that have emerged since the nineteenth century, such as precaution, prevention, preemption, preparation, and adaptation (resilience), which embody a strong and sustained commitment to the future.

These large formats are at the same time public and private segments of capitalist capabilities for the future and are supposed to clear a way for profit and power in the uncertainties of the respective futures. Their dynamics are neither short of violence nor of crisis, precisely because, despite their lack of simultaneity, they have developed their own bodies as well as modes of power and are thus an extraordinarily transformative and planetary force.

At the same time, each of these projects that aim at exploiting the “continent of the future” generates ever new globally effective visions, utopias, myths, and expectations (Jens Beckert) of great depth and breadth, which underpin the systemic viability of contemporary capitalism. These projects function as “generators of sense” (Georg Bollenbeck) and contribute pieces of guiding interpretations of the world and their “present futures.”

What happens when we construct, tell, calculate, write, hope, plan, or fantasize about the future? As a result, futures are made present (actual, real). Futures are defined by naming, interpreting, and framing, and, by doing so here and now, they are brought into the present – becoming “present futures.” All these futures at stake were and are named, understood, interpreted, and brought into their respective presents, thus making them current and ready for decision-making. The whole process is accompanied by the endeavor to minimize the difference between the then actual “future presents” and the current “present futures,” for each “present future” is kept between a here and now and a then and there. Present futures are present but at the same time absent because they have not happened, are not there yet, and may never happen. It is these presences in the present of something that has not happened, or that may never happen, that make such present futures the very subject of decisions, actions, or non-actions.

So it is about who leaves which “time print” (Zeitabdruck) of a present future in the future present. Secondly, it is necessary in the present to make decisions about ideas, models, imaginaries, narratives, and actions oriented towards the future that can be used to generate trust, credibility, acceptance, approval and, ultimately, security that this particular future present – though indefinite and not foreseeable – will actually occur. That is the punch line of “future politics.” It stands on shaky feet – but they are the feet of giants.

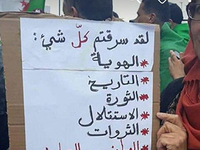

However, developing present futures also means taking them away from others, as British futurologist Barbara Adam put it: “We make and take futures” – for example, those of the exploited, the extremely poor, the homeless, the undocumented, prison inmates, or refugees. Here, any powerful and hegemonic future-making prefigures, shapes, and erodes the future present of those who follow. Crises, poverty, hardship, and austerity compress their time into the essential: survival in the distress of this present. Thus, it leaves no time for the attractiveness of the future, a better life and its imaginaries. Austerity is an uninterrupted attack on the future of the poor. To close this field of the future – this “warehouse of possibilities” (Luhmann) – and to exclude everything from power which could run contrary to dominant projects through concurrent substructures is a signum of the dominant future politics here and now.

However, it is not the reach of the great cultural models and narratives of capitalist promises of the future but their power to shape and their stability that have clearly eroded over the last 50 years. Over the last decade, the experience of the economic crisis, the rapid collapse of social-democratic-liberal patterns of order, and the rise of violent politics from the right have accelerated this destabilization. Nationalist and fascist narratives – not about markets but about guilty elites – are being revived and updated. Financialization and the financial crisis since 2008 devalued and destroyed millions of imagined future presents. The new, predominantly cultural paths of the future that have been reactivated or combined from these experiences and possibilities since the turn of the millennium therefore increasingly rely on mega-trend breaks and disruptions in the economy in order to enforce regressive retro-cultures from the right. Thus, political counter-narratives of the past gain weight and stabilize themselves institutionally and economically.

Those who want to criticize, reform, or radically transform today’s capitalism obviously have to deal with the fact that capitalism is for the first time in history a society of the future which operates with probable, plausible, and possible futures – whose current mantra, of course, is the massive invocation of narratives of the politics of the past.

Rainer Rilling, University of Marburg, Germany <rillingr@mailer.uni-marburg.de>