Since its establishment, the eurozone has followed proposals influenced by the great liberal economist Friedrich Hayek, especially the insulation of monetary and fiscal policy from national politics and thus from democratic processes and control. This project has been realized through a supposedly independent central bank and an institutional framework which requires heterogeneous economies to adhere to hard currency rules – even if, as in the gold standard era, these rules do not work to all countries’ advantage equally. The eurozone’s market orientation has become more obvious since the beginning of the global crisis. Even if some political forces within the project of European integration were initially in favor of social welfare, since 2010 the management of the crisis, especially in relation to Greece, has signaled the defeat of the vision of a “social Europe.”

Since 2010, a hard-core economic liberalism has been imposed on Greece, beginning with the country’s exclusion from international markets. Over the past six years, governments of various political orientations (social democratic, right-wing, left-wing, technocratic, temporary, and coalitions) have hastily imposed dozens of new laws and regulations within the framework of the so-called “Memoranda of Understanding,” a series of agreements between Greece and its international creditors. In order for Greece to gain access to loans to service its payment and debt obligations, austerity measures have been imposed, along with business-friendly legislation, privatization, and further shrinking of the Greek welfare state – already shrunken since the mid-1990s.

Beginning with Memorandum I, through today’s Memorandum ΙΙΙ, fiscal discipline has become the new doctrine. Threats, pressure and more or less open psychological terrorism from creditors regarding the effects of a possible “Grexit” (Greek Exit from the European Union) have prevailed despite intensified resistance, involving hundreds of strikes, demonstrations, protests and occupations, and new social movements and political parties opposing austerity agreements.

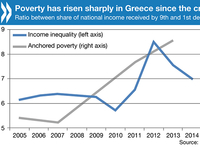

As a result of the austerity policies, since 2010 Greece’s GDP fell by more than 27%, a decline comparable to that of the US’s GDP in the 1930s. Living standards have deteriorated drastically; wage and pension cuts have ranged from 20% to 50% along with increasing emergency taxation; large parts of the population have been driven into poverty. In the public sector, expenditure has been rapidly reduced, thousands were dismissed and recruitment frozen; at the same time, fast-track procedures allowed the government to privatize many remaining state assets. Public organizations – ranging from publicly owned enterprises, to schools, hospitals or even asylums – were closed or merged with little consideration. Remaining institutions were overloaded, and thus unable to meet increased social needs, leading to a radical degradation of public services, including health, education, and social welfare.

With unemployment soaring from nearly 9% in 2006 to 27% in 2014, Greece’s working classes no longer see any prospects for a better future: it is clear that the economy will not recover soon. With more than half of Greece’s young people unemployed, and with intensified precarization of working conditions, newcomers to the labor market face severe problems. Families are less able to support children and the elderly due to wage and pensions cuts – challenging the Greek familistic model and the residual welfare state that was never as fully developed as in Northern Europe. Although this familistic model is sometimes considered a symptom of an underdeveloped capitalism – a view that is reflected in the “modernizing” reforms set out in the EU Memoranda – there is currently no evidence that Greece is moving towards any kind of European welfare state. Treating Greece’s familistic model and the residual welfare state as needing “reform,” creditors have insisted on deregulation and a shift to a market model – meaning that today, social protection remains available only to those who can afford it.

This deregulation has not been the outcome of any kind of dialogue between social actors, or any social consensus. National and supranational decisions taken in non-transparent ways through “emergency procedures” – representing both the creditors’ priorities and those of domestic elites – have fused during the crisis, blurring the lines between the corresponding tasks and responsibilities of national and international political actors. Greek voters have been excluded from political decisions, with conferences of the Eurogroup and the Economic and Financial Affairs Council replacing parliamentary functions. The imposition of a “technocratic government” in 2011, with an international banker serving as prime minister, has been the high point of this process. Meanwhile, democratic tools were rendered ineffectual, with referenda cancelled or treated as cancelled throughout the crisis period.

Karl Polanyi’s idea that the separation between economy and society is inherent to market liberalism is nowhere more identifiable than in Greece today. This separation constitutes a form of liberalization fostered by state intervention. Far from being a contradiction in terms, as Polanyi explained, the market system has always been a product of deliberate state intervention. This pattern is evident also in the Memoranda agreements, which constitute perhaps the broadest and most detailed political interventions in the history of the European Union.

In Polanyi’s rendition of nineteenth century capitalism, liberals blamed the crisis or malfunctioning of the self-regulating market on specific social groups. Similarly, in contemporary Greece, the prevailing narrative blamed society for the country’s situation: laborers enjoyed overly high wages, public employees were too numerous, social benefits too generous, public property too large. Thus, supervised austerity has been presented as legitimate punishment, designed to end the general profligate behavior in order to help the market to recover.

Greece’s crisis management is part of a strategy for the institutionalization of austerity throughout the eurozone. One of the instruments has been a Fiscal Compact which gives supposedly non-political European authorities enhanced surveillance of national budgets. But the crisis also brought to light the structural deficiencies and frailty of the European Monetary Union. As the eurozone’s economies have been reoriented toward a competitive neo-mercantilism, far-right and neo-fascist forces have increased their electoral influence. Optimism about European integration has gradually given way to political appeals for more national and state sovereignty – concepts that, only a few years ago, were considered outdated. Proposals from the camp of “more Europe” and “more political integration” now sound rhetorical; the eurozone’s elites are more concerned with strengthening economic liberalism, opposing any effort to ease austerity or fiscal discipline for countries under structural adjustment programs, or to increase funds for labor and public investment, much less for debt relief.

Punitive austerity, constitutionalized fiscal discipline and neoliberal, intra-European colonialism have worsened conditions for labor and created further precarization, deepening social deregulation and political instability in Greece and elsewhere. As long as no convincing plans offer a route out of austerity, asymmetries between national economies and class inequalities will increase, strengthening the sense among ordinary citizens in different countries that key decisions will be taken somewhere else, by some impersonal international elites; in that climate, Euroskepticism, anti-globalization demands and arguments for breaking up the eurozone will attract broader audiences. The question is what political form these demands and arguments will take, and which social forces will be dominant. Will those struggling for democratization and a break with neoliberalism prevail? Or will Europe’s far-right be able to promote a deeper nationalist turn? Up to now, Polanyi’s pendulum of the “double movement” suggests that market forces and their political representatives have emerged victorious, leaving democracy wounded and raising prospects of dark future scenarios.

Maria Markantonatou, University of the Aegean, Greece <mmarkant@soc.aegean.gr>