Greek Bailouts as State-Corporate Crime

December 02, 2016

The international academic community has recently sought to define “state-corporate crime” – that is, illegal or socially-harmful actions created through the interaction of political institutions of governance and economic production and distribution.

From a political and a research point of view, the term corresponds to what is often called “corruption,” but there are two important differences. First, the effort to criminalize these acts seeks to protect human rights and prevent social harms; these acts involve far more loss of life, physical or other harm, and loss of property or money, than more commonly recognized criminal acts like murder, attempted murder, theft, etc. Second, the roots of this crime are closely tied to ordinary political and social action: the interdependence of the state and capital – either by directly converting public money into private contracts or by providing facilities and promoting specific policies – lies at the heart of our capitalist society.

Moreover, these state-corporate crimes often involve a further dimension. Thus, “crimes of globalization” add an interesting dimension, when supranational institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, cause real social harm to entire populations. The top-down policies and economic programs consistent with the interests of powerful countries and multinational companies have drastic effects on human lives, mainly in “developing countries,” when programs such as “Debt Repayment” lead to political instability, then to paternalistic or clientelist systems of governance, that then spawn organized crime, corruption, authoritarianism, state repression, use of torture, and even the possibility of genocide.

In Greece, where we have been living under the implementation of Policy Memoranda defined by government agreements and supranational organizations, such as international lenders, we have seen human rights violations and widespread social damage. The measures implemented under “bailout programs” have directly affected living conditions, violating the human rights which Greece is obliged to respect, protect and promote under domestic, regional and international law. The drastic adjustments imposed on the Greek economy and society have brought about a rapid deterioration of living standards and are incompatible with social justice, social cohesion, democracy, or human rights. What human rights have been violated? Let us go through some examples.

- The Right to Work. Labor market reforms imposed by the Memoranda have severely undermined the right to work in Greece, causing grave institutional breakdown. Destroying longstanding collective bargaining agreements and labor arbitration resurrected individual employment agreements as the prime determinant of employment conditions. Successive wage cuts and tax hikes brought massive layoffs, eroded labor standards, increased job insecurity, and created widespread precariousness, pushing women and young workers into over-flexible low-paid jobs. The minimum wage was reduced to a level below Greece’s poverty threshold.

- The Right to Health. The 2010 Economic Adjustment Program limited public health expenditure to 6% of GDP; the 2012 program required reducing hospital operating costs by 8%. Hospitals and pharmacies experienced widespread shortages while trying to reduce pharmaceutical expenditure from €4.37 billion in 2010 to €2 billion by 2014.

- The Right to Education. Specific measures in the Memoranda cut the recruitment of teachers, forced transfers of teachers through labor mobility schemes, reduced teachers’ pay, merged and closed schools, increased the number of students per classroom and extended weekly teaching hours. Teaching posts have been left unfilled, 1,053 schools were closed and 1,933 merged between 2008 and 2012. Budget cuts left many schools without heating.

- The Right to Social Security. The Memoranda-imposed spending cuts diminished social benefits, including pensions, unemployment benefits, and family benefits. Since 2010 pensions have been cut on average by 40%, falling below the poverty line for 45% of pensioners. • The Right to Housing. Greece abolished social housing in 2012, as a “prior action” before offering a rental subsidy to 120,000 households, and housing benefits for elders. New laws and regulations allow rapid eviction procedures, without judicial trial. In 2014 over 500,000 people in Greece were either homeless or lived in insecure or inadequate housing.

- The Right to Self-Determination. The wholesale privatization of state property, especially through “fast-track” procedures, violates constitutional rights and provisions which guarantee the principle of popular sovereignty, property, and protection of the environment.

- The Right to Justice. Creditor-imposed measures require Greece to reform its judicial system, including substantially increasing fees. Recourse to courts has become financially difficult for citizens – especially when they have experienced drastic cuts in salaries and pensions.

- The Right to Free Expression. Since 2010 legislative and administrative measures have restricted freedom of expression and assembly – the right to free expression being systematically and effectively challenged, and the freedom of assembly violated. The authorities have prevented legitimate protest against Memoranda-driven policies, prohibiting public meetings, repressing peaceful demonstrations, making pre-emptive arrests, questioning minors, and torturing antifascist protesters – often in collaboration with vigilantes from the proto-fascist Golden Dawn party.

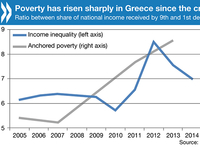

Today, 23.1% of the Greek population live below the poverty line; the relative poverty rate almost doubled between 2009 and 2012, and nearly two-thirds are impoverished as a consequence of austerity policies. Severe material deprivation increased from 11% of the population in 2009 to 21.5% in 2014; in 2013 over 34% of children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The measures have dramatically worsened inequality, with the poorest 10% of the population losing an alarming 56.5% of their income.

At the same time that Greek society has experienced human rights violations and widespread social damage, the legislative agencies have created a “policy of privileges,” further enabling corruption. This legislative initiative is multifaceted and leads to criminal immunity regimes, either in the form of a preventive exclusion of prosecution for specific individuals and groups – especially in contracts or public concessions, such as Siemens, armament programs, and privatization – or in the form of repressive legislative intervention in already pending criminal trials involving the limitation, suspension or termination of pending prosecution. Ironically, even as creditors urge Greece to crack down on tax avoidance, they seek to abolish a 26% withholding tax on cross-border transactions.

State-corporate crimes go beyond the individual criminal or deviant act as they become not the exception but the rule, the main feature of an era where anomie prevails – that is, where existing collective representations and the collective consciousness have been weakened. Such state-corporate collusion now represents the “spirit of the times” of our modern era.

We are facing an urgent challenge: What can be done to combat out-of-control state-corporate crime in a time when – much like the fascist period of the early twentieth century – formal social control, modern institutions, and scientific discourse are distorted by the prevailing structures of governance, production, and civil society?

It is important for us to continue to dream of a better world. Besides, although this symbiosis of state and business has been in existence for a long time, it has never been fully accepted. This is a dynamic process, and as scientists and citizens we should continue to expose it and question it.

Stratos Georgoulas, University of the Aegean, Greece <s.georgoulas@soc.aegean.gr>