Greece: A History of Geopolitics and Bankruptcy

December 02, 2016

Founded in 1830 in the very southern cone of the Balkan Peninsula encompassing the Peloponnese, Southern Rumelia, Euboea and the complex of Cyclades islands, the Greek state resulted from an imperial geopolitical accident rather than from an economically-expanding, national industrial bourgeoisie. Instead of reflecting national-revolutionary processes led by industrial capital against a feudal mode of production – as was the case, for example, with Prussian’s Junkers or Italy’s Piedmont – a limited Greek state was perceived by Western imperial powers as a geostrategic necessity, as part of an effort to deter Russia and Egypt’s territorial expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean. Geopolitical factors were paramount to Greece’s founding – and today, geopolitical/geostrategic questions are of crucial importance in understanding the historical origin of the Greek debt crisis. Since the founding of the modern Greek state, Greece’s important geographical position has been used by the West, not for the benefit of Greek society, but for its own advantage.

Nineteenth Century Ties to Global Finance

In order to conduct the war of independence against the Ottomans, Greek elites borrowed large amounts of money from the West. In the 1820s, Greece received two loans of £800,000 and £2 million respectively. A primitive Greek state apparatus experienced its first bankruptcy in 1824-25, when it could not service the loans received from France and England. In 1832-33 another loan of 60 million (in golden francs) was contracted and entirely consumed for the expenses of the regency and the maintenance of the army. That loan led to another Greek bankruptcy in 1843.

Between 1827 and 1877-78, Greece was excluded from Western financial markets. During these five decades and beyond, governments resorted (rather unsuccessfully) to internal borrowing while encouraging investment projects from wealthy diasporic Greeks, whose comprador capital, together with that of Jewish and Armenian merchant classes, was prominent in the Ottoman Empire. With low levels of industrial development, and unable to pursue economies of scale due to its small size, Greece was marked by a backward peripheral economy and a deeply-dependent polity throughout the nineteenth century; in 1893, Greece declared bankruptcy once again.

Yet, despite its dilapidated finances and its unsophisticated banking and industrial sectors, Greece was always viewed by Western powers through the prism of their imperial geopolitical interests. As the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires retreated, new spaces opened up for Russia and West European imperialism, now renewed by new actors such as Germany and Italy. Christian Balkan micro-states offered the West splendid opportunities, providing proxies in ongoing wars against the Ottoman Turks. By the end of the First World War, the Ottomans were pushed outside Europe, and the borders of the Balkans/Eastern Europe and the Near/Middle East were re-drawn.

Conquering land and incorporating populations – not all of whom were Greek – Greece saw substantive industrial activity in the first two decades of the twentieth century under the liberal-nationalist leadership of Eleftherios Venizelos. Under British sponsorship, Venizelos led a losing proxy war against Kemalist-nationalist forces in Asia Minor. The aftermath was a total catastrophe for both Greece and modern Turkey. Although Greece saw the inflow of some 1.4 million Christian refugees, it achieved ethnic homogeneity for the first time in its history while Turkey, having lost its most enterprising merchant classes, relied heavily on a state-led authoritarian form of economic development, and failed to achieve ethnic or religious homogeneity.

Without a robust economic base, and with its ruling political elites closely tied to imperial interests, Greece could not capitalize on its geostrategic advantages. Thus, instead of its geographical location serving as an asset, it became a permanent liability. This translated directly into a balance of payment problem which, coupled with constant internal borrowing needed to fund a clientelistic and corrupt state machine, repeatedly produced unsustainable debts.

The Financial Crisis of 1929 and its Aftermath

In the wake of the 1929 global financial crisis, Greece suffered a fourth bankruptcy in 1932. Afterwards, the dictator Ioannis Metaxas pursued an import substitution industrialization policy, substantially improving the country’s balance of payments. Moreover, as the imperial torch was passed onto the new global hegemon, the USA, the Cold War produced dividends: Greece’s geopolitical importance guaranteed a massive inflow of American capital and loans while marginalizing Greece’s domestic left communist forces during “the Golden Age of capitalism.”

Yet, once more, Greece remained peripheral and deeply dependent. Characteristically, in the 1960s, when the Governor of the Bank of Greece, Xenophon Zolotas, went to the US ambassador in Athens to ask for a loan, the ambassador replied by pointing to a geopolitical conflict. Effectively, the ambassador said that if Greece wanted a loan, then it had to accept Dean Acheson’s plan for Cyprus – a plan secretly negotiated among NATO powers proposing partition of the island between Greece and Turkey, dispensing with Archbishop Makarios, who was at that time Cyprus’s elected leader and a founder of the non-aligned movement. Thus, the geopolitical issue and the debt problem were dealt with through a straightforward swap. Such was the importance of Cyprus for NATO and the West that the USA, via the CIA, instigated a military dictatorship in Greece; democracy was only restored in 1974, when Cyprus was partitioned.

From the 1950s through the mid-1970s, Greece did not manage to catch up with the Western core. Yet throughout this period – and in contrast to the demand-led Keynesian policies of the West – Greece pursued policies that would later be termed neoliberal. Its economic development was supply-led and pro-monetarist, largely because of Cold War politics. Although the pro-Soviet Communist Left had been defeated during the Civil War (1944-49), it still enjoyed widespread popular support, which meant the conservative government feared any attempt to open up politics in civil society. Both political participation and demand-led economic policy remained stalled until 1974.

But after 1974, successive Greek cabinets under right-wing Constantine Karamanlis (1974-81) and socialist Andreas G. Papandreou (1981-89, 1993-96) shifted Greek policy-making to a demand cycle, replenishing the state machine with their party-political personnel, nationalizing major private enterprises and, especially in the 1980s, funding Greece’s welfare state through unscrupulous borrowing (both external and internal) rather than through taxation. Even as it entered the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1981, Greece continued to pursue demand-led policies at a time when most of the West was already shifting to embrace neoliberal globalization/financialization.

Time and again, geopolitical considerations figure prominently: Greece was admitted to the EEC five years ahead of Portugal and Spain as part of a strategy to stabilize NATO’s southern flank, at a moment when US fixed capital investment in Greece was drying out. In the 1980s, German and French capital increasingly dominated the Greek economy, and pushed the country to adopt a neoliberal agenda so that it could use Greece as a launching pad from which to spread financial services across the Balkans.

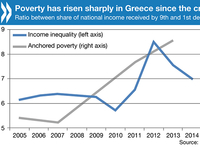

Deteriorating Economic Situation in the Eurozone

Over the following two decades, and especially after the country’s entry to the eurozone in 2001, Greece’s competitive position deteriorated sharply. Traditionally profit-making industries, such as textiles, disappeared. Financial and banking services dominated Greece’s economy, spreading out to the Balkans and the Near East. Public assets were privatized one after another. The country’s dependence on external and domestic borrowing increased to such a degree that, given the opening up of public assets to foreign capital acquisition and the loss of monetary sovereignty, one wonders whether the term “dependence” adequately describes the country’s global economic standing.

When the global financial crisis trickled down to the eurozone, Greece suffered most, because it was and is the weakest link of the neo-imperial financial chain of capital accumulation. Twenty years of neoliberal financialization, followed by acute austerity measures and bail-out agreements, have solved none of Greece’s historical economic problems: industrial backwardness; institutional malaise; massive current account deficits and high debt to GDP ratios; massive budget deficits and fiscal problems. What is needed is robust public investment, an effort to build up new industrial and agricultural sectors based on niche production, such as solar energy and green growth. At the same time, an independent foreign policy could take advantage of the country’s geostrategic position and its pacifist mission in the turbulent Balkans and the Near East. If this cannot happen within the eurozone as it is currently structured, then it is the eurozone that has the problem, not Greece.

Vassilis K. Fouskas, University of East London, UK <v.fouskas@uel.ac.uk>