Mondragon’s Third Way: Reply to Sharryn Kasmir

August 06, 2016

As scholars conducting research on cooperatives, we would like to thank Global Dialogue for opening up debate about coops, and for allowing us to respond to Sharryn Kasmir’s assessment of the Mondragon Cooperative published in Global Dialogue 6.1 (March, 2016).

Critical commentators of cooperatives, such as Spain’s famous Mondragon Cooperative, often argue that “facing competition, coops either degenerate into capitalist firms, or founder.” Given that Mondragon is clearly not foundering, many critiques – including Kasmir’s – aim to show that Mondragon has degenerated into a standard capitalist firm with precarious working conditions. This critique usually has two elements: the proliferation of temporary workers and the international expansion of non-cooperative subsidiaries. In the present article, we offer some data showing that instead of giving up their cooperative principles, Mondragon’s members see these challenges as opportunities to strengthen and enhance their model. In our own research, we identify a third way for the cooperative, a new non-capitalist competitive cooperative model.

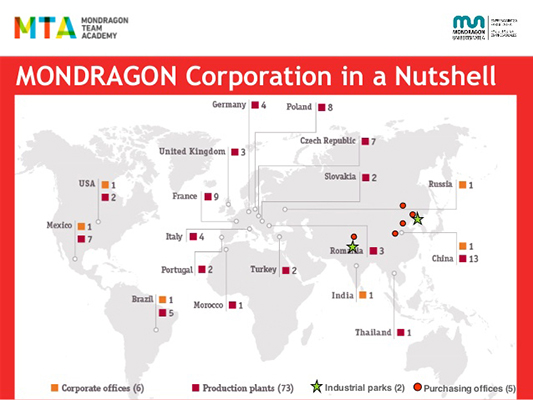

For more than 60 years, the creation of quality and sustainable jobs has been Mondragon’s central goal. According to its 2014 Annual Report, Mondragon is currently a group of 263 organizations, including 103 cooperatives and 125 production subsidiaries companies. Together, the Group is responsible for 74,117 jobs. Throughout its history, Mondragon has been able to create jobs and to maintain them even during economic recession; whenever possible, the jobs created are permanent ones. Today, most of the non-cooperative jobs can be found in three areas: the distribution sector, Spanish industrial subsidiaries and international industrial subsidiaries.

Mondragon uses three distinct strategies to convert temporary jobs into cooperative ones. In the distribution sector, Mondragon uses the EMES plan (Estatuto Marco de la Estructura Societaria). Eroski, Mondragon’s distribution group, acquired another distribution group (Caprabo), and then merged the supermarkets of the two groups. In 2009, the Eroski General Assembly approved the EMES plan, giving all workers an opportunity to become partners in worker cooperatives. Although this plan is still in force, the Eroski cooperative has found itself in a difficult situation, facing huge losses, and is now in the midst of a process of internal restructuring to reduce and refinance the accumulated debt. This is not the best context for inviting (non-cooperative) workers to become members.

A second strategy involves the conversion of industrial subsidiaries into mixed cooperatives, allowing workers to become members – an alternative which is only feasible when the companies are viable, and when both cooperative partners and subsidiary workers are willing to extend membership. This has happened in several cases: Maier Ferroplast Limited which belonged to Maier Cooperative Society (2012); the Victorio Luzuriaga Usurbil cooperative (2004); Fit Automotive (2006); and Victorio Luzuriaga Tafalla cooperative (2008). These are neither unusual nor isolated examples of how to cooperativize industrial subsidiaries.

The third strategy concerns international subsidiaries outside the Basque Country which are said to represent the degeneration of the cooperative model. The Group has created international subsidiaries to assist the maintenance or even expansion of employment in the parent cooperatives. From this point of view, this strategy has been successful, since the internationalizing cooperatives have created more jobs than those that stayed at home. Contrary to what some critics claim, figures show an increasing percentage of workers who are members. According to Altuna (2008), in 2007 members composed 29.5% of employees. By 2012, members made up about 40.3% of the total workforce.

In 2003, Mondragon’s Eighth Congress decided that the Group’s main aim would be to expand cooperative values, promoting participation (in management, capital and benefits) by extending the Corporate Management Model into Mondragon’s international subsidiaries. Though the effort is well-intended, many obstacles stand in its way. The transformation of these companies into a cooperative business model involves well-known economic, legal, cultural and investment barriers (Flecha and Ngai, 2015). For instance, some national legal frameworks do not recognize cooperative models; many workers lack the economic resources needed to become a member; and in some subsidiaries, many workers don’t understand the very meaning of a cooperative. Mondragon’s culture arose over sixty years in the Basque Country, and has been transmitted from generation to generation. Transferring this culture to another context is not easy. Nevertheless, there have been some successes. For instance, Angel Errasti (2014) describes the integration of trade union representatives into the Administrative Council of the subsidiary created by Fagor Electrodomésticos in Poland, which represented a breakthrough for worker participation in company management.

Mondragon raises many complex questions about the role of cooperatives in today’s competitive global economy. Mondragon’s cooperatives must operate in a competitive world so that, sometimes, failing to internationalize would risk losing the chance of creating new jobs in Spain and abroad. Although cooperative companies are a minority and capital companies set the rules of the market, this does not mean that there is only one path to survival in a global economy. The Mondragon group has been able to approach internationalization in innovative ways. When subsidiaries are created abroad, Mondragon’s priority has been to maintain jobs and preserve locally-rooted cooperatives, rather than to outsource or offshore production.

Mondragon has also succeeded in maintaining better working conditions than other cooperatives or capitalist companies. Even those who have been critical of Mondragon acknowledge this contribution as it is well known that today’s cooperative members hope that their offspring will have access to similar cooperative jobs that are both stable and of high quality. This principle of creating sustainable and quality jobs is also transferred to international subsidiaries. Thus, Luzarraga and Irizar (2012) show that in addition to complying with national and local regulations, Mondragon’s subsidiaries have improved labor conditions, for instance, in wages or training opportunities. Although Mondragon’s cooperative movement may not have been able to singlehandedly change the dynamics of global capitalism, it has nevertheless continued its historic effort to create a better world for workers and their communities.

References

Altuna, L. (ed.) (2008) La Experiencia Cooperativa de Mondragón, Una síntesis general. Eskoriatza: Lanki—Huhezi, Mondragon Unibertsitatea.

Errasti, A. (2014) Tensiones y oportunidades en las multinacionales coopitalistas de Mondragón: el caso Fagor Electrodomesticos, Sdad. Coop. Revesco: Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 113: 30-60.

Flecha, R. and Ngai, P. (2015) The challenge for Mondragon: Searching for the cooperative values in times of internationalization. Organization, 21 (5): 666-682.

Kasmir, S. (March 2016) The Mondragon Cooperatives: Successes and Challenges. Global Dialogue 6.1.

Luzarraga, J.M. and Irizar, I. (2012) La estrategia de multilocalización internacional de la Corporación Mondragón. Ekonomiaz, 79: 114-145.

Ignacio Santa Cruz Ayo, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain <Inaki.SantaCruz@uab.cat>

Eva Alonso, University of Barcelona, Spain <eva.alonso@ub.edu>