In recent years, global university rankings have praised the international outlook of Canada’s top research universities while top schools in the country have proudly announced their worldwide quest to hire the best qualified candidates. Following recent political instabilities in the US and the UK, Canadian universities have been ready to embrace the influx of Trump and Brexit dodgers and further their ambition for global reputation and excellence.

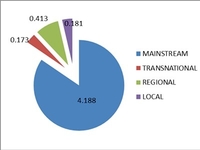

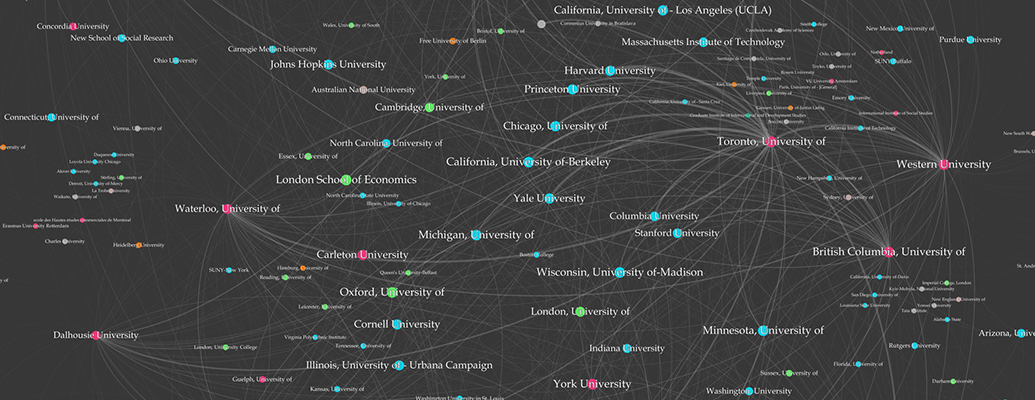

The Relational Academia project (www.relationalacademia.ca) investigates the shift in what it means to be a “good” university between the late 1960s and today in Canada. During the late 1960s through to the mid-1990s – a period of rising nationalism and perceived American domination in Canada – a “good” university was committed to employing Canadian instructors and teaching Canadian content for the economic, moral, and civil benefit of its citizenry (i.e., the Canadianization Movement). In contrast, over the last two decades, the mission of the “good” university has changed. It is now about increasing international engagement from students, staff, faculty, and alumni, and increased international presence and prestige. To document the nature of this shift from domesticity to globality, we collected the educational credentials of 4,934 social scientists working at Canada’s top fifteen research-intensive universities (the U15 group) between 1977 and 2017.

Examining the national origin of the faculty’s doctoral credentials, our results illustrate substantial increases to the proportions of Canadian-trained hires at lower- and middle-tier English-speaking U15 schools over the past 40 years, effectively Canadianizing – or de-Americanizing – their social science faculty. During this time, however, the University of Toronto, McGill University, and the University of British Columbia have remained heavily dominated by faculty trained in the US (over 70%). Between 1997 and 2017, three English-speaking nations – Canada, the US, and the UK – accounted for more than 90% of national origin of the PhDs of all faculty, with Global South schools – led by two former British colonies, South Africa (six placements) and India (four placements) – placing only 19 PhDs (less than 0.5%) at U15 schools.

Beyond the changing political economy of the Global North’s research-intensive universities eager to increase their proportion of international students, can one really talk about “international faculty” at Canada’s U15 schools? The national origin of faculty’s first degree reveals that over the last twenty years, the proportion of scholars at higher-tier universities who earned a bachelor degree outside Anglo-American countries has doubled from 9% to 18%. In 2017, half of these were faculty from 34 Global South countries who earned their PhD from an American university.

In the higher echelons of Canadian academia, internationalization can be two things: either another word for Americanization or US-mediated internationalization. Our research highlights America’s central position in the asymmetrical circulation of knowledge, students, and scholars across the globe. But more importantly for the national context, it also showcases Canadian schools’ dominated dominant position that contributes to the English-language dominance in the global field of social science, while at the same time being subject to a dominated domestic condition where US scientific capital reigns.

François Lachapelle, University of British Columbia, Canada <f.lachapelle@alumni.ubc.ca>

Patrick John Burnett, University of British Columbia, Canada <pjb@sociologix.ca>