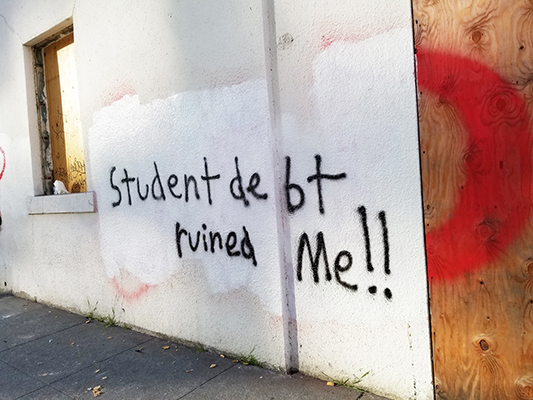

In many nations, post-secondary education has become synonymous with labor market prosperity and higher education has been hailed as the great equalizer in class mobility. While higher education is as important as ever to prosperity, however, rising tuition rates have led to an exponential increase in student debt. This trend is well documented, but researchers have lagged behind in determining how student debt affects new university graduates. In particular, one question begs to be answered: how does student debt affect new graduates’ transition to the labor market? Using nationally representative Canadian data on 2010 university graduates collected three years after graduation, this question, along with whether the effects of student debt are moderated by socio-economic background, is the focus of my dissertation research.

First-generation university students are at a disadvantage in financial, social, and cultural capital compared to second-generation students. They have fewer social network connections to find relevant employment after graduation, less knowledge of resume building and navigating the university field, and less financial support from family leading to greater reliance on student debt. Thus, it is not surprising to find that student debt adversely affects the labor force transition of first-generation compared to second-generation university graduates. Using advanced regression techniques, I find that high levels of student debt are associated with first-generation graduates reporting that they could not wait for the job they wanted after graduation, that their current job is not what they had hoped for, and that they had to move cities or countries to find employment. Further, compared to second-generation students, indebted first-generation graduates have a higher probability of temporary employment status, have had a greater number of employers in the three years since graduation, have fewer job benefits, and lower incomes both two and three years after graduation. Not surprisingly, given their greater desperation in finding employment after graduation and their experiencing greater precarity in the labor market, I also find that indebted first-generation students report lower job satisfaction, lower life satisfaction, and are significantly less likely to say they would do their degree again if they could go back in time compared to both first-generation students without debt and second-generation students with and without debt. These findings have significant implications for modern evaluations of university as the great equalizer.

These findings suggest that when student debt is used to provide access to higher education it exacerbates inequality and renders the equalizing effects of university null. Student debt creates desperation in the job searches of first-generation university students and the consequences of this desperation is greater job precarity which leads to reduced job quality and income. The finding that indebted first-generation graduates report that they would not do the same education if they could go back in time is particularly alarming. In sum, this research provides support for government policy to shift away from student debt as the means of providing access to higher education and to instead provide access through grants and reduced tuition.

Mitchell McIvor, University of Toronto, Canada <mitchell.mcivor@mail.utoronto.ca>