Read more about The University and Sociology

The “Sociology Wars” in Canada

by Neil McLaughlin and Antony Puddephatt

August 06, 2016

British universities are changing, in ways so fundamental that it is not easy to predict where it will end. Certainly working and studying in a university here today is a very different experience than it would have been just a decade ago. Stefan Collini recently maintained that “what we still call universities are coming to be reshaped as centers of applied expertise and vocational training that are subordinate to a society’s ‘economic strategy’” – a summary that echoes John Holmwood’s 2014 valedictory message as British Sociological Association president. He concluded that Britain’s university system now “serves a renewed patrimonial capitalism and its ever-widening inequalities.” The effects of these changes upon sociology as a discipline are not yet entirely clear, but there are some worrying signs.

Funding: From Central Grants to Student Fees

Historically – that is, before the Thatcher and Blair governments – British universities were quasi-independent charitable organizations. Student numbers were nationally set, and each university received appropriate funding based on various formulae. It was generally recognized as an “elite” system: only ten percent went on to higher education, while most young adults went through a complex system of technical and vocational education, apprenticeships and “on the job” training.

Under the Thatcher government, however, the destruction of the British manufacturing sector gave rise to talk of a renaissance through a “knowledge economy,” leading Blair to emphasize “education, education, education” as he argued that 50 percent of Britain’s children should go to university. In this way, and at great speed, universities became a key part of the government’s economic strategy – a shift made clear when responsibility for higher education was moved into the Department of Trade and Industry. Today, that responsibility rests in the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, whose most recent policy white paper – Success as a Knowledge Economy: Teaching Excellence, Social Mobility and Student Choice – reveals how a once utopian idea can provide the ideological platform for reactionary change.

This strategic shift was facilitated by a change in funding for Britain’s universities, involving a move away from central government funding to a system based almost entirely on student fees. In 1998, student fees were set at £3,000 per annum by the new Labour Government; since then, student fees have risen to £9,000, with further rises anticipated. There are important variations in the devolved administrations of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, but in England, higher education has been expanded through the accumulation of student debt, facilitated through a complex loan system.

The new funding system has been a critical driver of change. Universities compete with each other for students, with important pedagogical consequences: instead of being seen as pupils or apprentices, students are now customers. Perhaps paradoxically, the introduction of a “market” for students has been accompanied by various forms of state surveillance.

In 2005 the Blair government replaced a labor-intensive system of Quality Assessment (something which had attempted to improve teaching though inspectoral visits and the imposition of rather standardized classroom procedures) with a National Student Survey (NSS) – something like a consumer investigation, which collected and published students’ evaluations of all courses and degrees. These data (which included the proportion of students receiving first-class degrees) quickly became incorporated into league tables of the “best” universities, brought together and published by national newspapers.

Currently the government is planning to enhance this evaluation system by introducing a more complex set of inquiries reflecting a Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), which takes account of student retention and graduate employment as well as student evaluations. Although each of these measures has been shown to be fallible, the government plans to construct a new TEF grading system on the basis of which “we would expect fees to increasingly differentiate”.

From Research Assessment to Research Excellence

Under the “old” funding system, university staff were expected to teach and to do research with a nominal 3:2 split between these activities. Publicly-funded, academically-staffed, Research Councils made additional research funds available through a competitive bidding process. The Thatcher government, already concerned by the radical and critical voices on campuses, insisted on renaming the Social Sciences Research Council as the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC); over time this organization has been increasingly tailored to the needs of the UK economy. More importantly, perhaps, a regular (nominally five yearly) review of research activity was introduced within university departments: the Research Assessment Exercise began rather informally in the 1980s, but from 1990 performance was linked to future research funding, breaking the link with the old grant-based system.

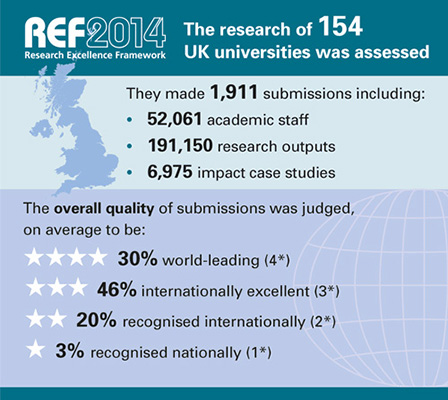

Subsequent iterations have seen this assessment process extended. In 2015, a name change to the Research Excellence Framework (REF) involved a further radical departure – including new efforts to assess the “impact” of published research and the “demonstrable benefits (made) to the wider economy and society,” broadly defined. Expert panels will “review narrative evidence supported by appropriate indicators, and produce graded impact sub-profiles for each submission.” These profiles will be graded on a scale, from “world leading” (4*) through “internationally excellent” (3*), to “recognized internationally” (2*) and “recognized nationally” (1*).

Over time, then, within universities, the external monitoring process has moved from the periphery to the center of discussion of research strategies, with words like “star” emerging centrally within academic discourse, alongside other strong words like “excellence,” “robust,” “rigorous” and “transparent” – constructing a seemingly incontestable narrative, one which many sociologists who should know better, have accepted. In this way of speaking, “Ref” has emerged as a new powerful noun in university departments along with “Refable,” “Ref-ready” and such like.

The Corporate University

These changes are part of a powerful neoliberal strategy that has transformed Britain’s public sector; the changes taking place in higher education parallel those that have reshaped the country’s health service, tax collection, policing and education more generally. Universities, competing with each other for students – now their main source of income – and competing for position in various league tables, have increasingly behaved more like profit-seeking corporates than charitable organizations.

University heads (Vice-Chancellors) no longer see themselves as the first amongst equals, but rather as Chief Executive Officers – paid accordingly, with their own pension scheme. When the current Conservative government removed a “cap” on student numbers the prospect of potentially-large surpluses – cash reserves stood at £6.5 billion in 2011 – encouraged UK universities to follow the US example of bond sales on the money markets, used to fund huge investments into new real estate. Many in the managerial elite view these new buildings as symbolic representations of their success.

In their search for more students (aka “cash”) universities, frustrated by visa restrictions on foreign students, have located large campuses overseas, offering some staff career-changing offers they can hardly refuse. While some ventures have been successful, others have been less so. In late 2015, Aberystwyth University spent half a million pounds to open a campus in Mauritius for British and international students, expecting to provide “new opportunities for students to have access to quality education, students who otherwise could not access these types of courses” – but by 2016, only 40 students had enrolled on a campus built to house 2000. As a former university head commented, scathingly: “The venture is madness. They would be better off concentrating their resources on high quality staffing and attracting more domestic students.”

All this speaks to a sector experiencing stressful changes, with real implications for the working lives of academics. The new corporate university tends to be further centralized by each newly-appointed Vice-Chancellor, who, determined to achieve objectives under the new arrangements, establishes top-down structures supported by increasing numbers of administrative staff. New administrative hierarchies emerge, as technical and financial “support staff” – formerly based in schools, departments and research centers but now migrating toward some central office. Increasingly, communication is conducted through email rather than personal contact, and once-simple operations, even organizing a meeting or booking a room, requires training and access to computer programs. As “metrics” become an essential management tool, they strengthen the pressure for standardization, which in many universities has been linked to new performance management systems. Performance-related pay also appears to be on the agenda – and, more significantly, so does an effort to move academic staff onto new, teaching-only, contracts.

The pathologies of bureaucratic “red tape” and of “goal displacement” in rule-governed structures, described long ago by Alvin Gouldner, are now obvious in British universities, especially in teaching and research assessment schemes – to the point where many universities now warn students that their own poor evaluations of their degree could affect its value in the labor market. The proportion of first-class awards is monitored, with encouragement for “more flexibility at the top end.” Having noted that students regularly criticize courses for providing poor “feedback,” some universities hold special sessions to explain to students what “feedback” is and when they will get it. In fact, some universities have appointed “Associate Deans of Feedback,” and some members of staff have been identified as “feedback champions.”

This “gaming” activity has been most advanced in relation to research assessment. In 2014 many universities departed from the custom of including all staff in the Research Evaluation, instead including only staff regarded as having highly-ranked publications and impact case studies. This outcome – which led to some universities being accused of “cheating” – involved various internal assessment procedures that were often invidious, and rarely collegial. Today, in the cycle leading up to the 2020 research assessment process, many universities have already put in place arrangements to monitor publications (“outputs” in ref-speak) with “Research Impact Managers” – all producing documentation in a convoluted and self-referential language of its own.

Decisions in these areas are invariably taken by high-level committees and communicated through didactic emails or “town hall” consultative meetings. Commenting on these developments, Professor Ben Martin at the University of Sussex noted the rise of “resentment, cynicism and sullen acquiescence,” a view confirmed by the latest Times University Workplace Survey, which found that while academics generally found their jobs rewarding, three quarters of them were deeply disillusioned with their university’s future plans and senior leadership. The survey also found that half of academic respondents worried about redundancies related to metric-based performance measures. More disturbing, perhaps, half of respondents said they believe their institutions have compromised undergraduate entry standards in their effort to compete for students, and that as individuals, they feel under pressure to award higher marks.

In this vein, Charles Turner, Associate Professor of Sociology at Warwick University, recently listed the following “problems that are really killing universities”: The commitment of vast resources that could be spent on library stocks to unnecessary and poorly designed new buildings; the awarding of first- and upper-second-class degrees to students who 20 years ago would have struggled to get a lower second; the use of administrators to make key decisions over matters of pedagogy; the desperate efforts to make some degree programs appear vocational when they are not and cannot be; and the endless tide of publications that nobody in their right mind would want to read – or write (The Guardian, June 1, 2016).

The Changing Place of Sociology

Sociology emerged quite late as a degree subject within British universities: only three viable centers existed through the early 1960s. Subsequently, a rapid and remarkable rise in the numbers of both departments and of students placed sociology in a strong position within universities today. This rapid rise involved a high degree of “openness,” with few attempts to establish firm professional boundaries around the discipline – an openness which allowed sociological thought to penetrate many different fields. However, a consequence of this openness has been a drift of some specialisms into other fields; good examples being the “sociology of work”, and the “sociology of education,” twin pillars of the past now taught in Business Schools and Schools of Education.

Sociology has changed in other ways. After making radical breakthroughs in the field of deviance in the 1960s and 1970s, this specialism has been re-framed as criminology, a topic in high demand, often taught in multi-disciplinary contexts involving social policy and legal studies. Health and the environment are also areas where sociology has been able to develop applied courses with high student demand. These changes, together with the shift in the core of the discipline towards interpretative approaches and issues of identity, have led some to suggest that the power of material structures and constraints is being underestimated, weakening sociology’s capacity to respond coherently to current events.

Similar questions are posed by the current research agendas of universities and the operation of the REF. The machine-like grind of the assessment cycle and the need for “four 3*/4* outputs” has seen academics opting increasingly for journal articles rather than monographs, and shortening field work to fit with the needs of the evaluation process. Some scholars have adjusted their aspirations to this process, others are giving up. Many have commented on the consequences for ethnographic work or for other research that builds on long-term contacts with communities. More generally the “performance” of a particular subject in the REF can reflect and also affect its overall standing and the ways it is viewed within each university. As such it was disconcerting to note the decline in the number of submissions in 2014 with only 29 departments involving 704 staff entered under the rubric of “sociology” (an all-time low) compared with 62 submissions involving 1,302 staff entered under the rubric of “social policy.” These ratios, being the inverse of the numbers on the ground, reflected changes in the research priorities of some sociologists toward more applied areas and the strategic choices of centralized university committees. As a consequence the panel was forced to report that it was only able to offer “a partial representation of the discipline.”

“Impact” of course, was central to this exercise: because this metric encourages researchers to work with external agencies, many academics have come to believe that critical work will be excluded or given a low rating. While there may still be room for some critical work (for example, in relation to environmental issues), the “Impact” measure in the social sciences implies a strong bias toward small-scale policy change, leading universities to actively encourage researchers to play it safe. The Research Council (ESRC) – itself the subject of close government scrutiny – has moved purposefully toward concentrating its funding around large major awards for complex projects often involving pan-university teams. This policy could increasingly leave smaller projects adrift.

These changes have evolved over the past 30 years. Today, we seem to be near a crisis point, raising questions about the very idea of the public university as a center of critical and scientific engagement. Current government policy seems likely to lead to the creation of new private universities and further intensification of competitive pressures across an enlarged tertiary education sector.

All this raises difficult questions both for the future and purpose of universities and the place of sociology within them. Significantly, sociologists have featured strongly in resistance to these changes with John Holmwood leading a group aiming to reclaim the public university in the UK. Its own alternative policy agenda, The Alternative White Paper for Higher Education, was launched at a major meeting in London in June. It points to the threats posed to students and critical research by the penetration of for-profit providers into the Higher Education sector, and concludes with a quote from the Magna Charta Universitatum of 1988, signed by 802 universities from all over the world: universities are “autonomous institutions” which “must be morally and intellectually independent of all political authority and economic power” – a goal that becomes more important the more it recedes.

Huw Beynon, Cardiff University, UK <beynonh@Cardiff.ac.uk>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: