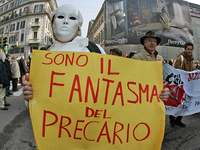

British Sociology in an Age of Austerity

July 13, 2012

The British Sociological Association (BSA) celebrated its sixtieth anniversary in 2011. At just over 2,500 members it is small in a world context, but in its own terms it is going from strength to strength. This is our largest membership ever and there are several other signs of vigorous health. We now publish four journals, we have the largest number of study groups in our history, our office and administrative staff is at its largest number and the last two annual conferences have been our largest ever. This year we have put on over 50 events. And all this, of course, in a country that has become infamous for the marketization of higher education, the ending of the publicly-funded university and the introduction of student fees, and which is undergoing damaging austerity. This is no coincidence: austerity is big business for British sociology.

The theme of the 2012 conference, held in Leeds, was sociology in an age of austerity. It was our largest conference outside London. Coming as I am to the end of my three-year term as President, I gave my Address on the public value of sociology in a time of austerity. In other plenary addresses, Michael Burawoy and Zygmunt Bauman debated the contribution of sociology in making sense of the social and political consequences of the economic crisis, and Stephen Ackroyd and Rosemary Batt spoke directly to the nature of that crisis, arising, as it does, as a result of the financialization of the US and UK economies. We had participants from 24 other countries and a huge number of presentations across several themes. We accepted 622 papers and had a reserve list of 62 waiting for dropouts.

Austerity has obvious effects on sociology as a university subject in Britain. There are threats that some departments might close or shrink in scale, and fears that student applications will fall as applications to university decrease generally under the impact of fees, or move toward degree choices with clearer career paths. Sociology teaching at Strathclyde University, for example, is closing and many sociology departments are reporting drops in student applications of varying proportions, some dramatic. On the other hand, some departments are thriving and report increases in student applications, again some dramatic. Some departments are advertising for new permanent posts. It might be too early to tell what the impact of austerity will be on sociology provision in Britain, although the BSA is keeping a watchful eye.

The impact of austerity on the discipline of sociology, however, is a quite different issue and here the situation is clearer. Our 2012 conference highlights two positive effects. Austerity has reinvigorated class analysis in British sociology and the sociology of work and industry, rebalancing it after the “cultural turn,” and renewed people’s engagement with the BSA. Forgive me if I here focus on the latter. As the discipline fragments both as a subject matter and in terms of its administrative location in multidisciplinary schools, it appears that sociologists are using the BSA as a way of maintaining their identity as professional sociologists. With the loss of the single-subject sociology department, teachers and researchers are spread across unrecognizable administrative units, often in small numbers, and treat the BSA almost as a functional equivalent to the old departmental structure, with our study groups replacing the departmental seminar, and the BSA itself serving as the locus of their professional identity. The BSA President Elect, John Holmwood, has made the theme of his term of office the necessity of sociology – and the BSA serves well as an example.

John D. Brewer, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and President of the British Sociological Association, 2010-2012