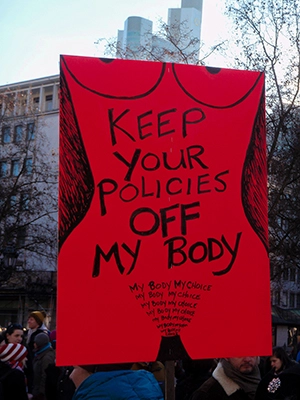

Women’s bodies have been at the center of various political debates throughout Turkey’s history as they have been in many other countries. In this paper, I will try to deal with different instances of how women’s bodies have become a canvas for different political conflicts.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, in Turkey’s early republican construction period, the regime defined the “new woman” of the Republic. The social status of women and their bodily practices (for example, the choice of clothing, sports, and exercise) were brought together within the same formula. Women would fulfil their duties and responsibilities to the Turkish nation through their bodies and practices.

In this period, one of the focal points in the discussion of the values of the newly established Republic was the cleavage between civilization and culture. The intellectuals and founders of the new regime argued that the civilization identified with the West would come to the country through modernization. However, how to preserve the culture that represented the country’s difference and specificity was also a significant concern. In this antagonistic positioning, women simultaneously represented the difference from the West and the similarity to the West. The “old” women, whose access to the public space was controlled through strict rules, were replaced with the “new” women, who had gained equality with men before the law but still maintained their traditional domestic roles.

As Çolak stated in his article “Citizenship between secularism and Islamism in Turkey,” every Turkish woman, as the new citizen, had to comply with a series of “idealized” and “civilized” symbols, images, and rituals reflected in their bodies. Sports were considered as the space where the new women were to be exhibited. First rally player Samiye Cahid Morkaya, as well as Halet Çambel and Suat Fetgeri, the first women from a Muslim-dominated country to participate in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, were among the symbolic names of this period.

Islamism, secularism, and the battle over women’s bodies

Women’s position in society was not a salient issue between 1950 and 1980. However, the period after the 1980 military coup, in which the regime in Turkey was transformed, witnessed the rise of the women’s movement. As Nacide Berber stated, “the independent feminist movement that emerged was, in the words of Sevgi Çubukçu, a ‘revolt’ movement that did not settle for legal rights, objected to the illusion that gender equality created by Kemalism was realized, and emerged with radical and fundamentalist demands.”

Another movement that rose after 1980 was the Islamic movement. This movement expanded in the field opened by the military regime, and increased its influence through the 1990s. After the 1990s, it became a recognized opposition movement with a static position on the political agenda. Once again, with the headscarf issue, women’s bodies were at the center of conflicts in the public arena. The headscarf was a significant part of the rhetoric of the Islamists, and the hegemons of that time viewed the headscarf as a symbol of Islam; they positioned it as an image of counter-secularism. Thus women were not allowed to work with headscarves in public service buildings, such as schools and ministries.

The growing women’s movement influenced the Islamic movement as well. With the influence of both the growing women’s movement and heated discussions around women’s participation in the public space with the headscarf, women took a very active role in the Islamic movement, particularly in local politics. In 2002, the AKP, an Islamic-oriented party, came to power. The struggle of women to take their place in public with their headscarves was an essential part of their rhetoric. They built their discourse on women’s freedom to wear a headscarf, framing their message in terms of women’s rights to do as they wished with their bodies. While in the early republican period, the rhetoric was based on the cleavage of civilization and culture, and in the current conflict it is based on secularism and Islam, in both cases women’s bodies are used as an image representing this clash.

With the rise of the Islamic movement in the following years, the discussion around the female body has gained new layers. Headscarved women are no longer the only debate with regard to the female body. Some Islamic opinion leaders have called on women to stay in line and abide by Islamic values with their bodies. Rights assumed by the women’s movement to have been guaranteed have become controversial again. One of these achievements was the 2011 Istanbul Convention that aims to protect women against all forms of violence and to prevent, prosecute, and eliminate violence against women and gender-based violence. After months of campaigns by some seemingly pro-government newspapers, Turkey, which in 2012 had no hesitation in signing the Convention, declared that it had reservations about it and withdrew in 2021. In fact, the Istanbul Convention debates reflected the tension around women’s rights in Turkey in different spheres. While homophobia was the most visible theme of the discussions, it was also evident that the political discourse, informed by concerns about changes in the traditional position of women, was calling the liberated women back to their homes.

Sportswomen as symbols

While the shock waves caused by the withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention continued, the Tokyo Summer Olympics started. Almost equal numbers of men and women from Turkey participated in the Olympics. Although they did not win a medal, the volleyball team know as Filenin Sultanları (“Sultans of the net”) in Turkey attracted much attention. One of the most important reasons for this was that the team’s success in the international sports arena took on a different meaning through a tweet posted by one of the Islamic opinion leaders on social media.[1] The tweet called on the girls of Islam not to be like female volleyball players, described as a part of popular culture, but to be sultans of modesty and propriety. The same women became a symbol of modern Turkey for the seculars. The women’s volleyball team thus quickly took on crucial symbolic meaning and the female body, once again, was instrumentalized and transformed into a symbol in the Islamic-secular debate.

While these discussions were going on, one of the team’s most successful players posted a photo with her girlfriend on Instagram. This time, as homophobic attacks increased, those who defended her with an anti-discrimination discourse and those who saw her as a symbol of moral corruption became polarized once again. However, right after the Olympics, there was the Women’s European Volleyball Championship, and the Turkish team was among the favorites. As a result of these developments, the Turkish Volleyball Federation, an institution affiliated with the government, made a statement supporting the player, stating that a person’s private life is private and that no topic other than the athlete’s success and contribution to the team should be on the agenda. Soon after, the athlete joined a team in Italy. As in other debates around women athletes’ sexual identity and as Pat Griffin explains in her article entitled “Changing the Game: Homophobia, Sexism, and Lesbians in Sport” the silence pact was quickly enacted and the issue closed.

In the present, as Aslı Telseren’s article in this issue also notes, while women’s bodies continue to be instrumentalized for political debates, women continue to struggle to make their own destiny.

[1] (in Turkish) https://twitter.com/ihsansenocak/status/1419296320267997187.

İlknur Hacısoftaoğlu, İstanbul Bilgi University, Turkey <ilknur.hacisoftaoglu@bilgi.edu.tr>