Why We Need a New Framework to Study the Far Right in the Global South

March 09, 2023

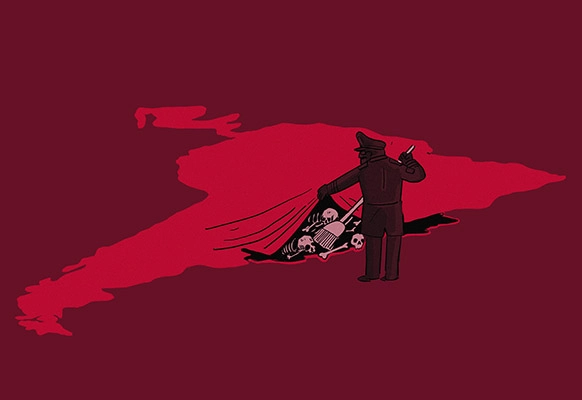

Vast scholarship has attempted to account for the rise – or resurgence – of the far right in the post-2010 world. In this short article, we argue that we need a new approach to understanding such a phenomenon, relying on a Global South perspective[1], in which colonialism and coloniality play a central analytical role (Masood and Nisar, 2020; Tavares Furtado and Eklundh, 2022). In the international literature, countries in the Global South are often presented as examples, case studies or variants of wider political events that place the United States and Europe at the center of their analysis. The problem of this colonized academic mindset is that countries like Brazil and the Philippines have experienced – and reinvented – one of the most radical and violent expressions of authoritarianism in the world. The profound damage caused by the Jair Bolsonaro administration on the environment is immeasurable but receives only residual international academic and journalistic attention, which hinders a better understanding of the most ferocious impacts that extremists have on the world.

Works that respond to the recent populist and authoritarian wave differentiate little between Global North and Global South specificities, relying primarily on analysis of European and American parties and movements (i.e., Brown, Gordon, and Pensky, 2018; Eatwell and Goodwin, 2018; Hawley, 2017; Hermansson, Lawrence, Mulhall, and Murdoch 2020; Inglehart and Norris, 2016; Mondon and Winter, 2020; Mudde, 2017; Mudde 2019; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018). The result is a limited – yet universalizing – repertoire that focuses on processes that account for recession in affluent countries, the collapse of the welfare state, migration issues, the impoverishment and resentment of the working class, de-democratization, and revolt against liberal democracy.

The context of the emergence of the contemporary far right

We must first inquire about the social, economic, cultural, and political context in which the far right (re)emerges; and a look at some emerging economies is revealing in this regard. When Narendra Modi (in 2014 in India), Rodrigo Duterte (in 2016 in the Philippines), and Jair Bolsonaro (in 2018 in Brazil) came to power, their countries were not collapsing in any previous form of a welfare state: the poor were emerging from poverty and authoritarianism was not a novelty, but rather it held a great promise. At the time, India and the Philippines were continually maintaining high levels of economic growth. Although Brazil elected Bolsonaro amidst a recession, the resurgence of the far right occurred alongside the country’ peak of economic development (Rocha, 2018). These countries were not facing a so-called refugee crisis, where immigrants would supposedly take the job opportunities of the autochthonous population. Instead, they were dealing with its racialized “internal enemies.”

The reappearance of the far right in colonized and peripheral parts of the globe – marked by persistent authoritarianism, conservatism, precarity, and coloniality – cannot be explained by an undifferentiated theoretical framework that was originally developed through European–American–Western lenses. In an insightful decolonial critique of the academic discourse on the far right, Masood and Nisar (2020) suggest that a comprehensive analysis of far-right populism must account for the heterogeneities of these movements across the Global North and the Global South. We are not suggesting that the experience in the Global North should be dismissed. The 2008 global economic recession, the 2016 Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, and the election of Donald Trump in the United States were pivotal events in generating contagious waves of authoritarianism worldwide and creating contextual incentives and opportunities for such movements. Countries in the Global North exercise power over the Global South and continuously export extremist ideologies. In addition, digital social media, an interconnected global economy, transnational networks of power, and conspiracy theories are some of the elements that make the authoritarian populist wave global.

Scholarship on the new far right: elements for a comparative and global agenda

Although the study of authoritarianism and populism in the Global South has a long tradition, scholarship on the new far right was slow to notice and encompass countries like Brazil and India as part of the same analytical phenomenon. The book The Populist Radical Right: A Reader, edited by Cas Mudde in 2017, is primarily regional because it focuses mainly on Europe but is perceived as universal. The Bolsonaro phenomenon attracted global attention. However, the epistemological route of this process seems to be dominated by colonized forms of knowledge production that persist in academia. Now, Brazil was incorporated into several projects researching the new far right as a case study from the Global South, and the same analytical tools are applied to it. Agreeing with Masood and Nisar (2020), we believe that this route should be turned upside down: some of the clues to the current global phenomenon arise precisely from the unfinished or hybrid modernity of the Global South.

Although a vast body of literature has analyzed the causes and the social conditions that led to the resurgence of populist rightist politics in southern countries, the understanding of the phenomenon remains narrow and fragmented because it lacks a framework within which to explore why several emerging democratic powers turned – again – to authoritarian politics. By focusing on southern experiences, we should recalibrate the lenses through which we understand the experience of colonized countries, expanding conceptual ranges and limits (rather than denying them). In a new agenda for research, we need to ask: What is new in the new right? What are the similarities and differences between Bolsonaro’s or Duterte’s authoritarian populism and the past dictatorial regimes? What kind of lessons can the Global North learn from countries that have long been marked by expressions of extreme politics? These renewed forms of extremism, neofascism, and authoritarianism are combined with harsh neoliberal rationality amidst social precarity and manifested through new technologies that enhance – and mainstream – populism in the twenty-first century.

Perhaps the main difference between the far right in the Global North and South is a matter of intensity and scale. Yet it is precisely such intensity and scale that must be understood and contextualized within historical particularities. For example, Trump and Bolsonaro may express similar intolerable statements through the same social media channels, relying on identical dog-whistle tactics. However, the effects of equally hateful attitudes will be utterly different in countries that present different degrees of economic development and democratic consolidation of their institutions. Most scholars of the far right exhaust the analysis of similarities among populist authoritarians, but it is equally important to pay more attention to the fact that a crusade against gender and sexual rights in the Global South will be much more visceral – and therefore harmful – than in the Global North.

The singularities of the Global South

Five aspects could constitute a new framework that account for some of the numerous singularities of the Global South:

1. Economic recession and political subjectivity: The literature on the far right has focused on the figure of the resentful impoverished white men. In contrast, colonized countries in the Global South have persistently been marked by conflict and recession. Yet, the imponent economic growth of emerging economies is also a subject that fosters new types of political engagement. While nostalgia for a glorious past is fundamental to understanding neofascist subjectivity in the Global North, this category needs to be rethought in the Global South.

2. The nuances of nationalism and xenophobia: Nationalism has different expressions in colonized countries. As mentioned above, some countries in the Global South might not have a glorious past to exalt, but a future to project. These countries are likely to have internal enemies (racialized minorities) rather than external enemies (immigrants or refugees). Although racism is at the core of far right projects, British white supremacy has different meanings from Hindu supremacy, for example.

3. The legacy of dictatorship and strongmen: Several countries in the Global South have suffered the consequences of bloody dictatorships that have resulted in a persistent violent ethos within the military and police towards racialized and vulnerable groups, who have never experienced any sort of democracy.

4. Religious and moral conservatism in non-secular democracies: Secularism is a core principle of established democracies. However, new democracies in the Global South struggle to overcome religious interference in political affairs, and the nefarious effects of fundamentalism, which acts as a disciplinary mode that controls bodies and sexualities.

5. Resistance: The far right has reappeared in the Global South and this is a phenomenon that seems to last. However, some of the most important reactions and creative responses against such a political wave come from feminist social movements in Latin American countries, such as Argentina and Chile.

Lastly, these five aspects are neither conclusive nor do they work in a one-size-fits-all perspective. They are suggestions that may shed light on features that countries in the Global South share in their everyday expressions of authoritarianism. We believe that more comparative studies are necessary for a better understanding of the causes and consequences of the far right in the Global South. Such work could change the way we understand this political phenomenon in the world today.

[1] See Pinheiro-Machado and Vargas-Maia, 2018. This article is also a shorter and adapted version of the introduction to our 2023 book.

References

Brown, W., Gordon, P. E., and Pensky, M. (2018) Authoritarianism: three inquiries in critical theory. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Eatwell, R., and Goodwin, M. (2018) National populism: The revolt against liberal democracy. Penguin UK.

Hawley, G. (2017) Making sense of the alt-right. New York, Columbia University Press.

Hermansson, P., Lawrence, D., Mulhall, J., and Murdoch, S. (2020) The International Alt-right: Fascism for the 21st century? London, Routledge.

Inglehart, R. F., and Norris, P. (2016) Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. Harvard JFK School of Government Faculty Working Papers Series. 1-52.

Masood, A., and Nisar, M. A. (2020) "Speaking out: A postcolonial critique of the academic discourse on far-right populism." Organization. 27(1), 162-173.

Mondon, A., and Winter, A. (2020) Reactionary democracy: How racism and the populist far right became mainstream. London, Verso Books.

Mudde, C. (2017) The populist radical right: A reader. London, Routledge.

Mudde, C. (2019) The far right today. John Wiley & Sons.

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018) "Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda." Comparative Political Studies. 51(13), 1667-1693.

Pinheiro-Machado, R. Vargas-Maia, T. (2018) "As Múltiplas faces do conservadorismo brasileiro." Revista Cult. 234, 26-31.

Pinheiro-Machado, R. Vargas-Maia, T. (2023). The Rise of the Radical Right in the Global South. London: Routledge.

Rocha, C. (2018) “Menos Marx, mais Mises”: uma gênese da nova direita brasileira (2006-2018). Doctoral dissertation, São Paulo, Universidade de São Paulo.

Tavares Furtado, H., and Eklundh, E. (2022). "Populism or the European condition?" Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 16(2).

Rosana Pinheiro-Machado, University College Dublin, Ireland <rosana.pinheiro-machado@ucd.ie> / Twitter: @_pinheira

Tatiana Vargas-Maia, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil <vargas.maia@ufrgs.br> / Twitter: @estocastica