Read more about On Being a Public Sociologist

A Life of Critical Engagement: An Interview with Issa Shivji

by Sabatho Nyamsenda and Issa Shivji

February 22, 2015

Nira Yuval-Davis, an Israeli dissident, has been a long-standing defender of human rights: a founder member of Women Against Fundamentalism, and the international research network of Women in Militarized Conflict Zones, a consultant to different divisions of the United Nations as well as to various NGOs, including Amnesty International. Known internationally for her research on gender, racism, and religious fundamentalism, her books include Racialized Boundaries, Gender and Nation, The Politics of Belonging, Women against Fundamentalism. She is Director of the Research Centre on Migration, Refugees and Belonging at the University of East London. In this essay she conducts an internal conversation with the renowned Israeli sociologist, now deceased, Baruch Kimmerling, on the different roads to public sociology.

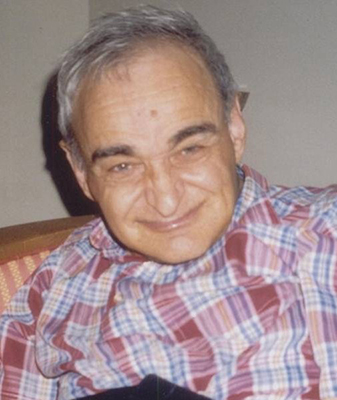

Baruch Kimmerling, was born in 1939 to a Hungarian mother and a Romanian father. After escaping the Holocaust, Baruch’s family immigrated to Israel where he grew up. He studied sociology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he researched and taught most of his adult life. After the bombing of its cafeteria in 1969, he turned to study the roots, history and actualities of the Israeli-Palestinian confl ict, developing an approach at odds with the offi cial Israeli narrative. As an outspoken critic of Israeli policies he was subject to wide and harsh recrimination. Through his writings and teaching he tried to infl uence Israeli public opinion in favor of a genuine democratic state that accepts all of its citizens without discrimination, renounces military aggressiveness and strives for peace through compromise and humanitarian approaches. Baruch Kimmerling died in 2007, faithful to his values and ideas, and very worried for Israel’s future. His books include Zionism and Territory: The Socioterritorial Dimensions of Zionist Politics (1983), The Invention and Decline of Israeliness: State, Culture and Military in Israel (2001); Politicide: Sharon’s War Against the Palestinians (2003).

Baruch Kimmerling, who suffered all his life from cerebral palsy and arrived in Israel as a refugee from Romania after 1948, was one of Israel’s most important and best known sociologists, not least because of his frequent contributions to the Israeli press.

Baruch and I were friends since we were undergraduates together at the Hebrew University, where Baruch remained throughout his life; I left after completing my MA in 1969, first to the USA and then to the UK. As research students we both rebelled against Shmuel Eisenstadt (who dominated Israeli sociology for nearly 40 years), but we differed in our sociological approaches and for many years also politically. In my twenties, I was radicalized to non- and then anti-Zionist analyses of Israeli state and society; after many more years and a systematic study of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and societies, Baruch reached similar conclusions – although he continued to label himself a Zionist. He developed important aspects of this field of sociology, while I “branched off” into what might be summed up as intersectional politics of belonging.

When Baruch died in 2007, as one of the Israeli, Palestinian and international social scientists invited to give papers at a memorial conference, I spoke on the existential anxiety of Israelis – especially those Baruch called “the Akhusalim,” the Ashkenazi, Secular and Labor Zionists who were hegemonic in the Zionist movement for most of the 20th century. I related this existential anxiety to several endemic factors, some common to all hegemonic minorities in settler colonial projects; others common to “neo-liberal risk societies”; and others more specific to Israel, relating to its character as a permanent war society as well as to the rising messianic fundamentalist Jewishness which threatens to undermine Israel’s quasi-secular regime.

To my astonishment, what I said was generally positively received – very differently to the way my analysis had been received in the past. (However, although the radical messages delivered by speakers were not challenged at the conference, the volume of our papers has still not been published, five years later, apparently because of resistance at the Van Lear Institute which hosted the conference.)

I would like to especially recommend Baruch’s autobiography[1], which is written with his usual wit and intellectual honesty, and which will also add to readers’ understanding of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. However, it raises some important questions in relation to public sociology. I limit myself here to two main questions.

Public and Professional Sociology

Baruch argues that he completely separated his public journalistic and professional academic work, a differentiation which flows from his Weberian belief in what Donna Haraway called “God’s trick of seeing everything from nowhere.” By contrast, I have argued for situated knowledge and situated imagination, following most feminist theorists and other radical traditions in the sociology of knowledge, Marxist and anti-racist. Rather than a relativist position – which insists that there are many truths that need to be judged on their own merits and therefore cannot be compared – I argue that one’s own standpoints (which include social locations, identifications and normative values systems, irreducible to each other but mediated by one’s life experiences and practices, fluid and contested as they are within particular structural and processual constraints) affect the ways one sees the world. Knowledge of “truth” can only be approximated by a dialogical constructive process, in which many situated gazes take part within particular spatial and temporal contexts.

My problem with Baruch’s dichotomy between the political and the professional is not just epistemological. Throughout my years as a sociologist and a political activist, I have found that the two modes of action nurture and provide critical insights for each other – with grassroots political activism helping to acquire empathetic understanding of other situated gazes on the one hand, and theoretical and empirical scholarship helping to refine and challenge some crude dichotomies of identity politics on the other hand. Moreover, often the line between the two seems artificial, when we consider why particular researchers embark on particular research projects and how they disseminate their research findings.

Baruch’s public interventions display the same pattern of overlapping preoccupations and mutual insights, starting from the moment he decided to study the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, after the 1969 cafeteria bombing on his university campus. I greatly doubt Baruch’s claim that he relied less on intuition in his “scientific” work than in his political work. As Baruch himself notes in relation to Kuhn’s theory of paradigmatic change, all data collection involves elements of selectivity. Nonetheless, I empathize with his frustration that people judged his sociological work only after reading his short public articles.

Baruch’s shifting paradigms of knowledge and his understanding of Israeli and Palestinian societies, however, raise a second issue, related to Baruch’s claim that his position as “a marginal at the center” was a precondition as well as the mode of his public sociology.

The Role of Social Location in Public Sociology

In his thorough, reflective, honest way, Baruch describes his first article in Israel’s oldest newspaper Ha’aretz, as a thorough and extreme attack on Sabri Jiris’ book The Arabs in Israel. Much later, Baruch realized not only that Sabri had been right, but that, having no access to archival material, Sabri underestimated the scale and deviousness of the means by which Israeli Palestinians had been controlled and their lands confiscated. Baruch acknowledges a similar shift regarding Ian Lustick’s book, Arabs in the Jewish State which he later justly praises highly. (Although he doesn’t mention it in his autobiography, when my co-edited book Israel and the Palestinians was published in 1975, he wrote to me as a concerned friend, recommending that I avoid including it on my CV. Many of the articles, including mine, correspond quite closely to Baruch’s later writings.)

Over the years, Baruch was able to reassess his understanding of the Israeli and Palestinian societies and conflicts; he became a wonderful public sociologist, whose writing influenced wider Israeli opinion in important ways. My understanding of various issues has also grown and changed throughout the years; I hope that like Baruch, this will continue till the day I die. However, I would like to take issue with two of Baruch’s claims.

Firstly, Baruch suggests that he developed his new perspective and understanding on his own, with little influence from the work of others whose works he’d read and with some of whom, over the years, he had spent many hours debating. This non-dialogical construction of self and of knowledge seems to misrepresent the process of knowledge and attitude acquisition. Ironically, it undermines the raison d’être of public sociology, which aims to present alternative analyses and presentation of facts.

Secondly, Baruch argues that he was able to become a public sociologist because, unlike the rest of us at the margin, he was trusted as “one of us.” In other words, he was “legitimate” in the eyes of the elites. Baruch suggests that this enabled him to be published in the mainstream Israeli press (which is indisputable), while others with a similar analysis (e.g. the members of the radical socialist and anti-Zionist organization, Matzpen) were less visible in the public arena because their views were considered illegitimate. This legitimacy, he suggests, is a precondition for effective work as a public sociologist.

Baruch suggests that his contingent acceptance as “one of them” stemmed in part from his attacks on books like those of Jiris and Lustick – the repudiation of analyses that he later came to respect. But this view leaves us with a major theoretical, as well as political, conundrum: must one “prove” oneself a trusted member of the collectivity, before one can accumulate the social capital required to be effective? What if that process of accumulation involves initially undermining the very cause for which one later becomes an advocate?[2]

There is no easy answer to this question. Given the state of contemporary Israeli society and politics – as well as other parts of the region and the world as a whole – I often feel close to despair, even though I try to cling to Gramsci’s politics of hope, optimism of the will and pessimism of the intellect. Although Baruch started from the center, rather than the margins, he came to feel similarly frustrated and depressed. I would love to hear from other readers of Global Dialogue about where they feel public sociologists, and other public intellectuals, must locate themselves in order to be effective.

[1] Kimmerling B. (2013) Marginal at the Centre: The Life Story of a Public Sociologist. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, translated by Diana Kimmerling.

[2] The strategy of many of us in the “illegitimate” margins has been, on the one hand, to work as public activists in a variety of specific (often unpopular) campaigns in Israel, as well as to establish dialogues and solidarity with Palestinians and Arabs with similar values and, on the other hand, also work with socialists and human rights defenders outside Israel and the Middle East in order to infl uence international public and governmental support of Israel.

Nira Yuval-Davis, University of East London, UK, President of ISA Research Committee on Racism, Nationalism and Ethnic Relations (RC05), 2002-6 and Member of the Program Committee for ISA World Congress in Durban, 2006 <n.yuval-davis@uel.ac.uk>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: