Read more about Sociology as a Vocation

The Vocation of Sociology: Collective Work on a World Scale

by Raewyn Connell

April 28, 2013

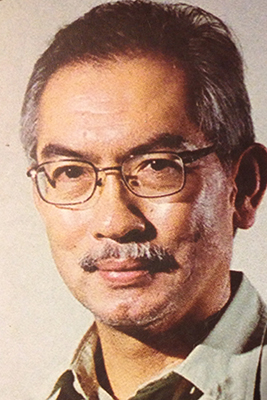

Randolf David is a public sociologist extraordinaire. A distinguished academic with an award-winning book, Nation, Self, and Citizenship: An Invitation to Philippine Sociology, Randy David is best known outside the university for his Sunday column, “Public Lives,” in the Philippine Daily Inquirer, which he began in 1995, and for his public affairs program on television, “Public Forum.” He has been an inspiration to legions of sociology students and brought sociological visions into the public eye.

Sociology was not my first love. I would say I found myself in it for reasons other than intellectual. I came to the University of the Philippines in the early 1960s hoping to be a lawyer, like my father, someone who could fix social problems, and not merely analyze them. In those days, one entered university not so much to get an education as to learn a profession.

If one was planning to study law, the prescribed preparation was political science or philosophy, or any of the social sciences. The pre-law requirement had just been relaxed to include any bachelor’s degree. This change somehow benefited the newer disciplines like Sociology.

I was originally an English major. I had planned to earn a living as a journalist after graduation while taking up evening classes in law. But, when you’re young, your best-laid plans could be derailed at any point. In my junior year, I took up the introductory course in Sociology as an elective, having heard that the professor in this course gave out high grades. I meant to boost my general weighted average, which had been pulled down by middling grades in difficult literature subjects.

Lo and behold, I fell in love with Sociology. Long after the course ended, I continued to read sociological books. On my senior year, to my father’s consternation, I shifted to Sociology. It was one of those contingencies that decisively shape one’s life. I met my future wife in those Sociology classes, and my exposure to social issues completely transformed my political outlook. Law would have led me to a conventional career in politics, for I was active in campus politics. I would have been in the same law class as many of the present senior legislators of my country.

Sociology gave me the attitude of mind needed for the sustained study of a troubled young society like the Philippines. To borrow a phrase from Hannah Arendt, I found myself seized by the pathos of wonder – the habit of disciplined observation that resists the urge to find quick solutions for every problem. The long-term structural orientation this engenders pairs nicely with radical politics. And in the late sixties, it was difficult for a sociologist not to be a Marxist.

But, the Marxism of an academic sociologist is not the same as the Marxism of a party member. While the latter is inevitably subjected to the imperatives of revolutionary praxis, where one is expected to suspend critical reflection for the sake of the organization, a Marxist sociologist typically spells trouble for any Leninist organization, because he will never give up the habit of reflexivity. He will always be an observer, more than an engaged participant. Apart from the ideology, his own actions usually become the object of his unrelenting deconstructive gaze.

That is why, I think, praxis has never been the sociologist’s strongest suit. One doesn’t turn to a sociologist for practical advice. The primary sociological commitment is to second-order observation – the observation of the way other people make distinctions in everyday life. The attitude the sociologist takes in the face of social complexity is one of awe at the way things are, rather than impatience or despair or panic over the seeming insolubility of social problems.

This being the inescapable character of the sociological stance, it is only logical to ask if there is any place in a developing society for a discipline that tends to revel in the observation of things rather than in the pursuit of solutions. Indeed I have asked myself this question many times.

Still, I would argue that at no other time has it become more important for society to make room for an intellectual attitude that, instead of offering quick solutions, questions the very frames in which the world is problematized. The vocation of politics requires a different temperament from that of a scholar. You can never be an effective politician or social activist if you are in the habit of subjecting yourself to constant self-analysis. To my mind, reflexivity is the political practitioner’s worst enemy.

I thought I knew this well enough to resist being drawn into the world of politics. But I was wrong. Sometime in 2009, I read the signs and arrived at the conclusion that the country’s unpopular president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, would, at the end of her term, seek a congressional seat in order to protect herself from political reprisals. Because we belong to the same congressional district, it dawned on me that I could stop her by putting myself up as a candidate. Instead of dismissing the idea as foolish, I made the mistake of entertaining it in a moment of conceit.

Before I knew it, I found myself cast in the role of a David who would stop the country’s political Goliath. It was a great story line in a nation that had been searching for messiahs. But, as a sociologist, I was fully conscious of the risks one takes when one crosses functional boundaries. I knew nothing of the specific problems of my electoral district. I had not previously run for any public office. I had no finances for an electoral run.

Most of all, I did not have the temperament for traditional politics. I knew that while I was standing up to power, I had no wish to pursue it. But having found myself at a point of no return, I began preparing to enter a world I had spent a lifetime interpreting but whose ways I could not have adequately grasped in the limited time that I had. On the day I was to file my candidacy, I decided it wasn’t worth squandering my family’s time and savings just to indulge a personal whim. My decision not to proceed was attacked by people, including friends, who had been waiting for a grand battle.

Armed with knowledge, as a sociologist operating in the public realm you may often find yourself having to stand up to power. If you wish to remain a sociologist, you must take care not to do so as a politician or as a member of a political party, but as part of the public. As a sociologist your mandate is to interrogate politics, not to seek to win in it on its terms.

Randolf S. David, University of the Philippines, Quezon City, Philippines

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: