The US and Cuba: Making Up Is Hard To Do

November 01, 2015

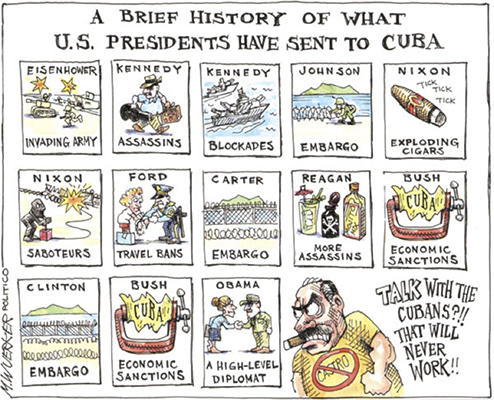

In a thirteen-minute address last December, President Barack Obama dismissed as a failure 53 years of a policy designed to strangle Cuba’s economy. The United States – or, at least, its Executive Branch – was ready to try a new approach, restoring diplomatic relations with an eye to becoming good neighbors and trade partners. To paraphrase José Martí, Cuba’s national hero and great intellectual of the late 19th century, negotiations had to be carried out in silence, for entrenched interests could have scuttled peace talks even before they began.

Suddenly, those interests were exposed as parochial and self-serving. The danger of counter-revolution was nothing compared to the threat posed by US corporations, which had been watching companies from around the world establishing themselves in Cuba, especially in tourism. Much more was possible: agriculture, cattle, light industry, tools, consumer goods, construction, housing and transportation, even joint ventures in high-tech biomedicine.

Today, businesses big and small support the president. More and more people travel under newly-relaxed rules. More and more Cuban immigrants and visitors now take for granted the freedom to travel between Miami and Havana. Miami’s hard-liners are mostly as old as Fidel and Raúl; new arrivals, who did not experience the loss of wealth at the beginning of the revolution, are taking their place. Today, the new policy looks like an unstoppable wave.

But, while the possibilities are immense, so are the complications on the road to normalization. Restoring diplomatic relations is only the first step.

The Updated Cuban Model

Years ago, before Obama’s announcement, Cuba began to debate a new and necessary economic approach. The discussions led to comprehensive guidelines involving grants of unused land, the legalization of small businesses, new autonomies for state enterprises, and support for agricultural and non-agricultural cooperatives.

Undoubtedly, Cuba must succeed definitively in generating much more food, substituting purchases abroad with home-grown foodstuffs. The all-important small farmers and cooperatives should see their incomes rise, creating a demand from new urban industries. With improved services and rising salaries, the people will enjoy much better material circumstances. But while that is the projection, the results so far are uneven. A host of factors complicate the picture, including the availability of basic agricultural inputs; dependable transportation between the countryside and the cities; refrigeration for produce; sufficient boxes and sacks; farm machinery and fuels and many other upgrades in a system long held back by inadequate infrastructure.

Cuban entrepreneurs are often inefficient, lacking skills in such aspects as small-business management, contracting, and general accounting – important not only for fiscal health but also for tax collection, a relatively new concern as the state shrinks and the private sector expands. The state sector – which will remain dominant, especially in sugar, tourism, mines, oil and refineries, health, bio-medicine, education, trains, air travel – must also improve productivity. Cuba faces also two unusual challenges: the need to consolidate the existing currencies (peso and convertible peso), and the aging of its population.

The first has long been a popular demand. The government is moving gradually, recognizing that citizens who now use primarily the non-convertible peso may find the stronger convertible currency out of their reach. The influx of dollars and goods from abroad – especially South Florida – affects households differently depending on whether they have supportive relatives abroad.

The aging of Cuba’s population is not unique, but it creates unique challenges. Cuba’s medical advances mean its people live longer than they did decades ago; but the emigration of well-prepared young people complicates the picture, as does urbanization. Decreasing percentages of young workers especially complicate the new land-use plans: agriculture needs youths, including those educated in agronomy, soil management, marketing, and related fields. Between the 2002 and 2012 censuses Cuba’s population declined for the first time since Cuba’s war of independence in the nineteenth century. The drop was due to low fertility and emigration; during this decade over 330,000 Cubans received legal permanent residence in the US.

While Cuba’s new economic plans involve efforts to raise agricultural productivity, new small businesses, improved management in state enterprises, the new port at Mariel, open (and potentially massive) tourism from the United States, and freer trade with all countries, should also contribute to a new prosperity.

The Continuing Interests of the US

The United States’ policy shift stems not from kindness, but from broader concerns. Much has changed in the region, including the success of organizations such as ALBA-TCP, Unasur, and Celac – none of which involve the United States, a sharp change from the past, when no inter-American organization could have avoided offering a place of honor to the United States. At the same time, Russia and especially China make inroads in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Traditional allies have resented the United States’ insistence that they accede to US policy on Cuba; at the United Nations last year, only Israel voted in favor of the blockade. The United States could not do away with Cuba. To the contrary, Cuba garnered respect and gratitude from countries around the world. Cuba won that battle, although peace is not assured.

The United States will likely pursue its goals of transforming Cuba into a dependent neoliberal island one way or another. That prediction holds irrespective of the party or president in power in Washington, even if US corporations find profitable trade opportunities.

The Elections of 2016 and 2018

What lies ahead? Obama’s presidency ends in 2016. It is possible for the Republicans to take the White House as well as both houses of Congress. The Republicans could take the White House; most of their current presidential candidates hew to regime change in Cuba as a promise unfulfilled. The Democrats have their own Congressional hard-liners; their leading presidential candidate, a committed neoliberal and practitioner of “soft power,” has said that she would return Latin America and the Caribbean to what they looked like during the years of her husband’s terms in office, before Hugo Chávez’s election in Venezuela. The federal legislation mandating the blockade can be undone only by a majority vote of the House and Senate.

In 2018, Cuba should have a new President, most likely the current First Vice-President, Miguel Díaz-Canel. He will take over the conduct of the new economy as well as the new society. He has declared that Cuba will continue to be socialist, even if market forces have space to operate and a new entrepreneurial class consolidates its standing.

Many countries are hoping for a reconciliation of the superpower and the stubborn island. It’s possible. The new policies – political, in the US, economic, in Cuba – favor the onset of an era of mutually-beneficial relations, but 55 years of disagreements are not soon forgotten. For now, we know one thing: The US and Cuba will remain 90 miles away from each other.

Luis E. Rumbaut, Cuban American Alliance, Washington D.C., USA <rrumbaut@uci.edu>

Rubén G. Rumbaut, University of California, Irvine, USA <lucho10@earthlink.net>