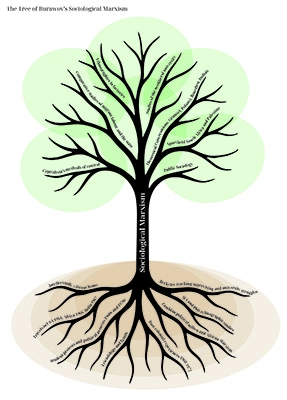

The indefatigable spirit and exceptional mind of Michael Burawoy was taken from us on 3rd February 2025. The callous act of violence of a hit-and-run driver in Oakland, California, put to rest the legendary scholar. Michael was my MA and PhD supervisor between 1995 and 2005. After I left Berkeley and moved to South Africa, Michael visited regularly and over the years became a very close friend and remained a mentor throughout. He’s been one of my fiercest critics and most supportive allies. While I have tried to frame Michael’s contribution to sociology and Marxism over his prolific life, I am no doubt biased and what I offer reflects the partiality of a student and friend who learned so much from her mentor. Michael always found ways to improve anything I gave him to read and I’m sure this piece is no different, though I hope he would be amused by my “tree of Burawoy’s sociological Marxism”.

The roots of the tree

Michael Burawoy was a rare breed of scholar with his unflinching lifelong commitment to both sociology and Marxism. He applied his formidable intellect to both fields and found a way to combine them in incredibly productive and innovative ways. His commitment to both stems in part from his personal biography. He came to both sociology and Marxism through lived experience that was etched deeply into his sense of justice and fascination with the social world. His parents were Russian Jews who left Russia for Germany in the 1920s where they did their PhDs in chemistry but then left Germany for England in the 1930s with the rise of Hitler. His parents’ home was an intellectually vibrant and politically engaged place. In the summer of 1964, Burawoy sailed across the Atlantic on a Norwegian cargo ship and spent the summer traveling around the USA selling books for a New York bookseller. The country was bubbling with the social energy of the free speech movement, civil rights movement, anti-Vietnam war protests, and urban uprisings. For the seventeen-year-old, the trip planted the beginnings of a sociological imagination that would find its moorings over the next few years during his forays traveling through India on third-class trains and hitchhiking across Africa.

After he graduated from Cambridge University with his mathematics degree, Burawoy took a job as a journalist in Johannesburg, South Africa, and after six months moved to the newly independent Zambia where he worked in the personnel department of a large multi-national company involved in the copper mines. Similar to the social vibrancy he experienced in the summer of 1964 in the USA, southern Africa was electric with political foment against apartheid and anti-colonial struggles. It was in Zambia that Burawoy was exposed to Marxism, post-colonial dynamics and intersections between class and race. His journey into sociology and Marxism solidified when he registered for a Master’s degree in sociology at the University of Zambia. The three-member sociology department exposed Burawoy to Marxism, the extended case method, ethnography, and articulations of race, caste and class. He came to understand the power of sociology and social theory in understanding the world. His love for sociology was cemented! For Burawoy, sociology married to Marxism provided powerful tools to understand the world and lay the basis for changing it for the better. Indeed, it was through his own personal journey of discovering the world that he developed his unwavering fidelity to both sociology and Marxism. By bringing sociology into dialogue with Marxism he found new ground in sociological Marxism – a branch of non-doctrinaire Marxism – that placed society alongside the state and economy. He never wavered from this course and had little patience for the fashionable rhetorical posturing often found in the academy.

Over the next 50 years, Burawoy would become one of the most important sociologists of his generation. He was many things: a legendary teacher, a devoted supervisor, a sympathetic friend and colleague, a non-doctrinaire Marxist, and an extraordinary scholar.

The trunk of the tree

Burawoy was an enthusiastic, even evangelical, sociologist and a brilliant Marxist who was gripped by questions about and the desire for emancipatory futures. He saw the role of sociology as to make visible the invisible, and the role of Marxism as to provide the tools to understand the social forces underlying the invisible. What made Burawoy so innovative was that he asked common questions in uncommon ways. For instance, while working in the Zambian copper mines, instead of looking at the way workers were responding to independence from colonial rule, he focused on the way management was responding, which led him to uncover the upward moving color bar as Africans entered management. Another example of his uncommon approach was that instead of looking for worker resistance on the shopfloor in his ethnography of the Chicago factory, he asked questions about why workers work as hard as they do, in an effort to better understand capitalism and its methods of control.

Burawoy understood that as long as capitalism exists, so too will Marxism. Like capitalism’s evolution over time, Marxism also must rebuild itself to reflect the problems of the times. For Burawoy, this took specific form in his sociological Marxism. Drawing on Gramsci and Polanyi, Burawoy’s Marxism looked at historically specific notions of society to understand capitalism’s longevity as well as the spaces of hope beyond capitalism. His ethnographic method made visible the micro-foundations of capitalism, and his extended case method elaborated these investigations of micro-processes with macro-sociology. He thus brought to Marxism historical specificity that helped elaborate a dynamic Marxist theoretical tradition and brought to sociology an anthropological method forged in Zambia that highlighted the importance of micro-sociological investigations for social theory. For Burawoy, understanding “society” and its role in capitalism was the linchpin of both sociology and Marxism. In his 2003 article “Sociological Marxism” he explains that “society” inhabits the institutional space between the economy and society. Drawing on Gramsci’s understanding of civil society interpenetrating the state and Polanyi’s “active society” pervading the market, he argued that socialism requires the subordination of the market and the state to society.

The branches of the tree

Burawoy refashioned Marxism first through his scholarship on labor regimes and workplace ethnographies, and then through his turn to civil society and the movements generated in advanced capitalism. This change marks a shift from the working class and the point of production to civil society as key to transcending capitalism. Burawoy’s first phase of sociological Marxism focused on the workplace also married to his ethnographic method of the extended case study. By working on the factory floor alongside other workers, he saw the way capitalism generated consent on the shopfloor while continuously adapting to the changing conditions. Through a number of workplace comparisons in copper mines in Zambia, migrant workers in California and southern Africa, and factories in Chicago and Hungary, Burawoy developed a “living” Marxism that helped shed light on continually changing dynamics of capitalism through micro-foundations on the shopfloor.

After a series of thwarted ethnographic studies in Russia in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Burawoy faced questions about the degeneration of socialism into capitalism rather than the evolution of capitalism into socialism. The fall of the Soviet Union was a turning point for Burawoy as he laid down his factory tools and turned from ethnographic methods to theoretical engagement with Marxism. He began by thinking through sociological Marxism and engaged deeply with Erik Olin Wright’s “Real Utopia’s” project. He then shifted to discussions between Marxism and a series of scholars: Gramsci, Polanyi, Bourdieu, and Du Bois. With the rise of neoliberalism and a new generation of resistance movements, Burawoy recognized the importance of struggles beyond the shopfloor. Thus, his theoretical forays also marked a shift from the point of production to civil society as a significant location for the emergence of new historical subjects. Michael Levien (in his 2025 article “Michael Burawoy, Sociological Marxist”) makes a similar point by showing that his theoretical interventions led Burawoy down interesting tributaries reconstructing Marxism. At this time he developed his “Tree of Marxism” with Marx and Engels as the trunk of the tree out of which grew a number of branches: German, Russian and Soviet, Western, and Third World Marxisms; Bakunin and anarchist syndicalism; and social democracy. He used the metaphor of the tree to show the evolution of Marxism as well as the way in which some branches wither and others grow.

As he rose to the apex of the discipline of sociology first as Chair of the Berkeley sociology department, then as President of the American Sociological Association, and then as President of the International Sociological Association, Burawoy also shifted his focus to the neoliberal university and sociology more specifically. Again, the influence of South Africa on Burawoy marked this shift as he developed his ideas about public sociology. On regular visits to South Africa in the 1990s and 2000s, Burawoy encountered a new lively sociology that was deeply involved in the society around it. The juxtaposition to sociology in the Global North led him to develop a schematic rendering of four types of sociology: public, critical, professional, and policy sociologies. For Burawoy public sociology was the most important and central for social transformation. He positioned public sociology as a crucial bulwark for engaging civil society against rising neoliberalism (what Burawoy referred to as third-wave marketization) and recognizing the importance of the nation-state. He also called for the development of a global sociology that is locally grounded while pointing to the global.

The tree of Burawoy’s sociological Marxism

Burawoy’s extraordinary intellectual journey can perhaps best be depicted in a tree of Burawoy’s sociological Marxism. Similar to his tree of Marxism, he grew sociological and Marxist roots from a formidable body of work through sociological Marxism. For Burawoy, the roots of his tree are an intellectually vibrant childhood home, his early years of travel overseas, encounters with post-colonial societies, engaged sociology and African Marxism in Zambia, student and political protests, education as transformative, ethnographic and extended case methods, comparative studies, the power of social theory, and understanding the forces of capitalism. The roots grew into the trunk of Sociological Marxism. From the trunk, robust branches grew consisting of investigations of micro-forces in factories in Zambia, Chicago, and Hungary, on migrant labor and the state, theoretical discussions with Gramsci, Polanyi, Bourdieu and Du Bois, studies of the neoliberal university, comparative analysis of apartheid in South Africa and Palestine, and public sociology (see diagram).

Burawoy saw Marxism not as a fixed paradigm, but as an evolving theoretical tradition that helps shed light on specific investigations into the workings of capitalism and its methods of control. In this way, sociological Marxism comes alive as an ever-growing and branching tree from which new ideas continuously sprout and past analyses are “revisited” and reshaped.

While I have tried to depict Burawoy’s extraordinary contribution to sociological Marxism in this short article, I am only scratching the surface. There is much more to glean from his prolific writings. And for those of us lucky enough to have been his students and colleagues, his extraordinary teaching, mentoring and supervising has left us with an inspiring guide and an incredible body of work to draw on.

Special thanks to Joanne Morrison for assistance with the tree diagram and to Vishwas Satgar and Peter Evans for their comments on this article.

Michelle Williams, University of Witwatersrand, South Africa <michelle.williams@wits.ac.za>