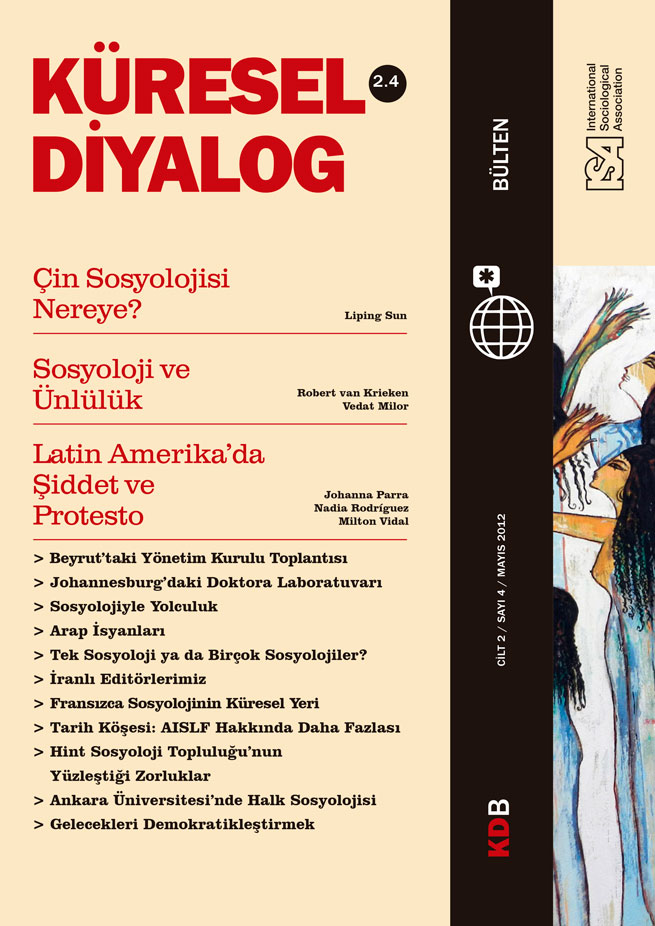

Read more about Violence and Protest in Latin America

The Violence of Emeralds

by Johanna Parra

Land Restitution in Colombia

by Nadia Margarita Rodríguez

July 31, 2013

Chile is a small country in the far south. According to the dominant view of world cartography, you can find us at the tip of South America. It is a place that draws international news headlines from time to time. In 2011, a movement led by college and high school students became increasingly prominent in an international scene already full of social protest.

We are part of the most unequal region of the world. A third of the population lives in poverty, suffering from old and new forms of violence, abuse, corruption, and squandering of scarce resources. In this context, men and women organize themselves in different ways to fight for their dreams, to demand respect for their fundamental rights, to demand that their governments fulfill their promises and make decisions that favor the common good. This is also true in Chile, of course. There are many sources of dissatisfaction that would have prompted Latin Americans to take to the streets of which many are more obvious than the social rights of high school and college students. One shouldn’t forget that this southern country was the starting point and inspiration for the main neoliberal policies enforced by Latin American governments since the mid-1970s, particularly in relation to college education.

Why, then, did these protests start in Chile? Why are they perceived as legitimate by so many in our country? Simply put, the neoliberal promise had burst. Indeed, the promise of making college education available for all took the worst possible turn: an increase in enrollment was possible only to the degree to which students and their families went into debt. University fees in Chile are among the highest in the world and most of them are paid by credit. In sociological terms, in a country where the distribution of income is brutally unequal[1], it is especially important that we conceive of higher education as a public good and as a decisive factor in social mobility.

The return on these families’ private investment in higher education is among the highest in Latin America and university fees are still on the rise. The limits on this increase will be set by family purchasing power. In sum, the relatively rich pay for the best basic education (elementary and high school) and benefit from the best universities (admitted on the basis of exam scores and/or purchasing power), while those with fewer resources and a mediocre basic education have to make substantial sacrifices to attend dubious institutions at a high cost. Thus, protest for a better education is a statement against social inequality.

Surprising many, the social movement in defense of public education led by students took off and gathered strength week by week. The content of the demands, the social force that was mobilized and legitimized, the international solidarity that developed are not confined to Chile. On the contrary, movements in defense of public education have also been successful in Uruguay, Bolivia, Brazil, Puerto Rico, Ecuador and Colombia. Nevertheless, it is useful for an international discussion and reflection to point to some of the characteristics of the Chilean case.

First, universities are still a barometer of social life. To insist on this historical constant may be naive, but it is often forgotten. Politicians who should be carrying out deep reforms of universities delay them because they think of higher education as a marginal issue, while economic leadership thinks that the deficit in higher education can be resolved by injecting resources from the public sector, the bank, families or all of the above. Big mistake! Universities have always been much more than a policy sector. All major social change is somehow connected to universities. Whether we think of the Jewish exile from the Persian empire of Nebuchadnezzar, the political debates of Plato’s Academy, the debates prior to the Protestant Reform with Luther’s thesis and translations of the Bible into German, of Calvinism in the University of Geneva, of Iran pre- and post-Khomeini, of China prior to the People’s Republic, the cultural revolution or Tiananmen Square, of Mexico pre- and post- the Tlatelolco massacre, universities are and will continue to be global institutions of major political and social importance. Thus, they must always be an object of major sociological attention.

Second, education at all levels, but particularly at the college level, cannot be subjected to a polarized tension between state and market. Humboldt was right when he argued a long time ago that state interventions get in the way of education. Latin Americans know that the state always embodies power that expresses itself in bureaucracy. Sociologists of education know that the most burdensome part of reforms is carrying them out. Nevertheless, even Humboldt argued that we cannot do without the state completely. We need to demand that the state guarantee the institutional conditions for education. We also need it to keep the University from becoming a battlefield for individual interests. In this sense, education is a public good and universities are public institutions, even if they are funded privately. Its teaching, research and outreach functions are essentially public. Their ability to give out diplomas is based on society’s faith in them.

Third, the student movement in Chile, and more generally in Latin America, rejects the commodification of education. The organizing logic of a market economy is incompatible with that of scientific training. Let us observe the collaboration between students and professors more closely. Education is always the result of collective efforts. It cannot be bought and hence cannot be commodified. Students can only become educated through their active participation in scientific activities. This is why we motivate them to become involved in seminar discussions, to write up reports, to become involved in research teams, to share and debate their ideas with other students. The idea that professors and students are buyers and sellers is not only misleading (and needs to be challenged for more than ideological reasons), it is an obstacle to reaching the goal of education. I find it appalling that colleagues in academia accept the view that their students are clients. Students require academic freedom, which depends in turn on the freedom of their professors. Yet this academic freedom is eroded by the market economy. If professors are considered service providers, that is employees and dependents on whomever owns the institution of higher education, then they, in turn, will use their students to advance their narrow interests.

Finally, we must say that student protest is good news for societies, universities and sociologists. The university is a place where society transforms itself into a research topic and, in the process, reaffirms itself. There have always been interests and power struggles in this self-awareness that have threatened academic freedom. However, these struggles have not been able to destroy the University. This is how we should look at the student movement in Chile, and beyond Chile in Latin America and the world. I think that the persistence of the movement benefits a democratic society. Society and university are again strongly linked by this student movement, providing a stimulating context for sociology. Those who say that the sociological narrative is in decline are wrong. Sociology is in good health in the southern part of the world and I hope this news will cheer you up, patient readers.

[1] Chile is an emerging country of the OECD. According to this organization, Chile has a Gini score of 0.50, which represents the highest inequality among the countries in this category (Society at a Glance, Social Indicators, OECD, 2011). This point can be illustrated further: the average income of the richest 10% of Chileans is higher than Norway’s, while that of the poorest 10% is similar to that of the population of Ivory Coast. The majority of Chileans (60%) have, on average, a lower income than Angolans.

by Milton L. Vidal, Academic University of Christian Humanism, Santiago, Chile

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: