Read more about Moroccan Sociology and the ISA Forum 2025

Revisiting Contemporary Sociology in Morocco

by Abdellatif Kidai and Driss El Ghazouani

Sociology in Morocco and General Sociology

by Kawtar Lebdaoui

March 14, 2025

Sociology emerged in the West during the Industrial Revolution as a means of social engineering in response to the imbalances and dysfunctions observed in the social fabric of the countries affected by that revolution. Since then, sociological knowledge has been the subject of debate and reflection concerning its object, methodology, approaches, etc. It evolved from the status of social thought to the status of a science, and in the English-speaking world – especially in the USA – was given the name “societology,” while the French and other Europeans adopted the term “sociology”: the name that has since stuck.

While the process of institutionalization of this science in European and Anglo-Saxon socio-cultural areas has been similar, its emergence and institutionalization have undergone a different process in countries of the Global South (or non-Western countries), and especially in Morocco, which is the focus of this study. The objective here is to enlighten the reader on the trajectory of Moroccan sociology and the challenges that sociologists in Morocco are called upon to take up, with the contribution of other sociologists who believe they live under the “power of knowledge” rather than the “knowledge of power.”

Institutionalizing sociology in Morocco: the pre-protectorate period

It’s worth recalling that Morocco was home to some of the most significant figures in the advancement of rationalism (Ibn Rushd/Averroes, 1126-1198) and social thought (Ibn Khaldun 1332-1406) in the Mediterranean region. However, as a “science of society” and scientific knowledge, sociology was introduced into Morocco to serve the purposes of occupation and destructure Moroccan society, while reconstructing it according to an imposed architecture in the name of a mission to civilize a country perceived as backward. Following the negotiations at the Algeciras Conference, Morocco was converted into a French protectorate. This was after having amputated its Saharan territories in favor of Spain at the Berlin Conference (1884-85), where the European colonial powers famously sat around a table and shared out the African continent.

During this period, while wishing to impose its right to occupy Morocco on the other European nations, France dispatched its spies and collaborators across the country to gather information likely to enlighten them on the situation in the country and the composition of Moroccan society. Their aim was to put in place what I call a “theory of domination,” which facilitated the “domination of Morocco” and the establishment of the protectorate. All this work culminated in the founding in 1904 of the “Mission scientifique du Maroc,” which published the Archives marocaines (Moroccan Archives) and later the Revue du monde musulman (Muslim World Review). In 1914, just after the protectorate status had been forcibly imposed on Morocco and in agreement with the Resident-General, a third publication was undertaken in collaboration with the Department of Indigenous Affairs and the Intelligence Service under the title Villes et tribus du Maroc (Cities and Tribes of Morocco).

Institutionalizing sociology in Morocco: the protectorate period

During this period sociology and related social and human disciplines were framed by a political vision of domination. Thus the social sciences constituted knowledge that served the civilizing mission that the occupying states – in this case, France and Spain – had arrogated to themselves and wished to impose on the country.

During the protectorate period (1912-56), few non-French researchers were allowed to research in “French Morocco” whereas the Spanish authorities tolerated the presence of researchers of other nationalities. Moreover, most of those who produced sociological and social knowledge were executives of the “protectorate authority” (civil and military controllers, senior administrative officials, etc.) while only few Moroccans were kept as informers (or even auxiliaries).

An overview of the works from the period reveals a situation where sociology was practiced in Morocco as a tool of penetration and submission, based on gathering information and intelligence to understand the country’s socio-political and economic structures and resources. However, certain nuances between areas of practice can justify the differentiated treatment that I adopt in the following sections.

The sociology of “French Morocco”

French sociology at the time advocated Durkheimism. At the same time, it built its perception of Moroccan reality around a dichotomy, cultivating conflict and antagonism between Moroccan components, with the aim to “divide and rule.” The knowledge generated was mobilized not only during the 27-year pacification period but also right up to independence.

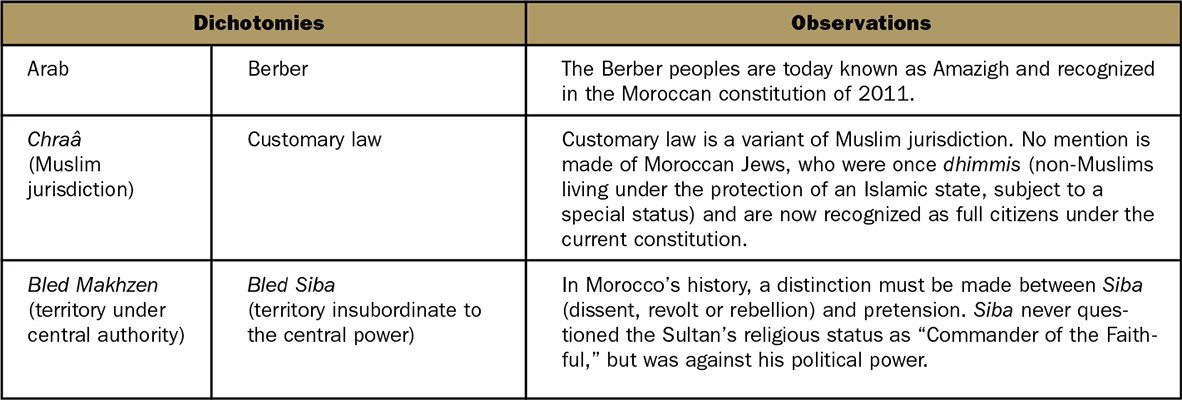

This duality produced monolithic entities that the so-called “academic” literature described asin the table below:

These dichotomies were incorporated into administrative entities. As a result, those in the first column were conceived as suitable for civilian control while those in the second column were to be managed by military controllers, according to a politico-territorial perspective in which the civilian zone was “useful Morocco” and the other merely “useless Morocco.”

The sociology of “French Morocco” privileged the colonist as the spearhead of this international mandate that France wanted to transform into colonization. The power of the Resident-General did not substitute the power of the Sultan but was superimposed on it and circumvented by vizier decrees. Methodologically speaking, this sociology tried to adopt the research methods and data collection techniques of the time. The main problem lies in the analysis and interpretation. Often, the collection of data and information and interpretation had the society of origin as a reference. This reveals an ethnocentrism both in the development of concepts and in the approaches not only in the field work, but also in the conclusions.

“Spanish sociology” in Morocco

In its zone of influence, Spain behaved in much the same way as France. It relied on information provided by so-called scientific missions and other informants as sources. The underlying idea was to distinguish the socio-political and territorial reality of this zone from its despoiled Moroccan territories: Ceuta, Melilla, the Sahara.

Spanish sociological knowledge was articulated through the notion of “Africanismo,” which refers to Moroccan-Spanish socio-historical “traumas” (Al-Andalus, the Battle of Anwal, and civil wars in particular). This became an ideological and cultural reference against Morocco in many forms. As a result, the social weight of the past between the two countries has prevented “voluntarist objectivism” in the Spanish approach to Morocco, hindered by the so-called “civilizing mission.”

We can conclude that “primary utilitarianism” in Spanish and similar sociological works was not a construct of a field of study or even a specialty; it was a mission tinged with religious humanism.

Sociology from other countries practiced in Morocco

Few sociologists from other countries were interested in Morocco, or rather were authorized to conduct fieldwork there, especially after 1912. Most were based in Tangier (declared an International Zone).

The Finn Edvard Westermarck stayed in Morocco from 1898 to 1939. The main reason behind his successful travels was his relationship with his friend Sidi Abdeslam El Bakali (Sheriff of the Jbala region), who provided him with protection on all his journeys. Just as did Carleton Coon, who published Tribes of the Rif in 1817, republished in 1966, Westermarck recognized the hospitality, understanding, and high degree of cooperation of the Spaniards and the society he studied.

If I chose these foreigners from different horizons to illustrate participation in this plural, polyglot sociology, it is to show the specificity of the Western-centric vision. That vision meant that anthropology (or even ethnology) was practiced as “exo-sociology,” while sociology, properly speaking, was seen as “endo-anthropology.”

The situation of sociology in independent Morocco

Since the country’s independence, sociology has been adopted in Morocco in a paradoxical way. On the one hand, it has been seen by the enlightened elite as a break with Mashreq’s cultural tradition and hence a key to modernity aimed at understanding and better diagnosing society’s ills so as to overcome them and move towards a better society. On the other hand, it has been seen by those in power as an inconvenient science.

Although Moroccan cooperation with UNESCO gave rise to the Institute of Sociology in 1961, its disbanding in 1970 took place against a backdrop of unfortunate events, the corollary of Morocco’s Years of Lead. Once the Institute was closed, sociology was integrated into the Department of Philosophy and Psychology, with a sociology major starting at the postgraduate level. PhD sociology studies are also offered. The curriculum has been Arabized, like all other humanities.

To counter the rise of critical thinking and its left-wing socio-political undertones, Sociology departments were banished in favor of Islamic Studies departments, which were opened in the 11 Faculties of Arts and Humanities that sprang up in the different regions of Morocco.

The colonial legacy

Despite its troubled past, sociology has been accepted as a Moroccan heritage in its own right. Moroccan researchers have appropriated this heritage by subjecting it to a “double critique” (A. Khatibi). They have targeted both the erroneous theses that support the theory of domination and the methods and techniques used to collect data and information, not to mention the way these are processed and used to support conclusions or constructs that do not reflect societal reality. This debate has not only focused on Moroccan studies but has also delved into the fundamental epistemological and cognitive terrain of the social sciences.

Thus, segregation has had its share of critics (P. Pascon, A. Taoufik, A. Hamoudi, etc.), as have other modes of analysis that have had their heyday. Colonial production, not colonialist production, was integrated into the work of Moroccan researchers. This debate was more dynamic and animated with the French school than with the Spanish legacy, which was under-analyzed (or even ignored), due to Morocco’s policy of Francophonization.

The arrival of Anglo-Saxon sociology

Anglo-Saxon sociology made its entry into Morocco with independence. Interest in the country was driven by geostrategic interests. Work on Morocco was particularly plentiful in the USA. So much so that Morocco became a research and immersion laboratory for those wishing to specialize in the Arab world, Islam, cultural diversity and so on (Clifford Geertz and his students are a case in point).

Distinguished Anglo-Saxon scholars were pioneers who then sent their students, and these students, now teachers, were in turn replaced by their students. This has given rise to a body of knowledge that Moroccans could not access due to the limitations of language, dissemination, and, above all, censorship. It was not until recently that graduates of English language and literature became involved in popularizing these works, either through translation or criticism. The same applies to other language and literature departments within the Faculties of Arts and Humanities, with the exception of French language and literature, which have long been involved in this debate. Thanks to bridges created between the various departments and even universities, sociology has been enriched and has become a feeder course for other specialties.

Today, there is an openness to the various foreign production on Morocco, especially since the reestablishment of sociology in the late 1980s, via new departments in all the Faculties of Arts and Humanities. Previously, sociology was only available at the Faculties of Arts and Humanities in Rabat and Fez. More importantly, studying sociology was seen as a left-wing tendency.

The emergence of a “Moroccan School of Sociology”: handicaps and assets

I have used these historical milestones to hastily sketch the context of the emergence of a “Moroccan School of Sociology” whose output is multilingual, but mainly in Arabic and French. Sociological writing in English and Spanish is now beginning to make inroads, as Moroccan researchers conquer new horizons in their quest for training and employment.

The institutionalization of a Moroccan School of Sociology has been handicapped by the aforementioned socio-political conditions but has also suffered from a poor governance of research in the social sciences and humanities. This is not only due to the compartmentalization from which sociology in particular, and most other specialties, suffered until the late 1990s, but also to the lack of financial resources, which have been insufficient or poorly managed and, generally under-utilized. Moreover, several public funding programs for social and human research have had little real impact on promoting it. Private funding has not kept pace with developments, especially with the deontological and legal vacuum in research activity regarding training, expertise, consulting or research. Even certain partnerships between ministerial entities in specific fields remain unresolved.

Several social science researchers have formed interest groups through associations within or outside universities. They have thus responded to social demand for training, consultancy, and expertise. Students have found this to be an ideal opportunity to improve their skills under the professional guidance of their professors. Examples include the Center for Studies and Research in Social Sciences (CERSS), the Mediation Space (espacemediation.org), and the Regional Observatory of Migration, Spaces and Societies (ORMES), among others.

The latest university reform has seen the creation of several laboratories, but they are handicapped by their bureaucratic structure, cumbersome financial management, and the tensions of “Homo academicus.” Despite this, they have been able to enliven university life through their diversified activities and provide a framework for inter-university exchanges at home and abroad.

To compensate for these handicaps, hybrid initiatives have been launched by individual researchers or groups of researchers, in the form of flagship events. These include the National Sociology Day (Journée nationale de Sociologie), an annual traveling event organized by the Instance marocaine de Sociologie and the Social Sciences Springtime (Printemps des Sciences sociales) organized by Al Akhawayn University with Mohammed V University in Rabat. These hybrid initiatives have taken the form of para-university and even peri-university work. They have helped open up the university to its social, economic, civil and even political environment and represent spaces for informal exchange and improvement, where different generations of researchers from various backgrounds, as well as young MA and PhD researchers, can meet.

Prospects and international outlook

Thanks to its multilingual nature, sociology in Morocco has to some extent been sheltered from the trends experienced in other parts of the MENA region, such as Arabization or Islamization.

Since the 1990s, bridges have been built with the various private higher education and training establishments for cross-border university education. This has helped to create stronger cross-fertilization with Anglo-Saxon production while offering sociologists and other social science researchers opportunities to enrich this emerging Moroccan school. This internationalization of academia and research has allowed many sociologists to move to institutions in the Gulf countries, either as immigrants or for occasional stays, and even to be active in networks funded by these countries. These opportunities have helped the Moroccan School of Sociology spread its influence and connect with other countries in the MENA region, offering possibilities beyond institutional mobility.

With the restructuring of sociological practices within the Instance marocaine de Sociologie, heir to the Réseau marocain de Sociologie (Moroccan Sociology Network), and the annual organization of the National Sociology Day, sociology in Morocco is organizing itself while promoting a “Moroccan School of Sociology.” In this way it is contributing to the history of sociology, while striving for an international dialogue referring to the “power of knowledge” rather than the submission of sociology to the sole “knowledge of power.”

Hosting the 5th ISA Forum of Sociology in Rabat (Morocco) from July 6 to 11, 2025 is for us an opportunity to celebrate diversity while respecting deontology so that sociology and the social and human sciences are not affected by utilitarianism or other forms of power and that academic freedom and the independence of the researcher are recognized.

Abdelfattah Ezzine, President of Espace Médiation (EsMed) and founder and national coordinator of the Instance Marocaine de Sociologie, Morocco <abdelfattahezzine@hotmail.com>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: