Read more about Moroccan Sociology and the ISA Forum 2025

The Institutionalization of Sociology in Morocco

by Adbelfattah Ezzine

Sociology in Morocco and General Sociology

by Kawtar Lebdaoui

March 14, 2025

Several obstacles hinder the production of a comprehensive study of the themes, approaches, and methods of sociological thought in Morocco. The initial impediment has been the dearth of interest among researchers in advancing the discipline and the paucity of documentation about sociological data. These include, but are not limited to, the absence of comprehensive thesis reviews, the scarcity of published book reviews, the lack of thematic bibliographies, and the rarity of colloquium papers. The second obstacle is the national character of postcolonial independent sociology. The formative years of “national sociology” were shaped by the influence of nationalized teaching faculty in the immediate post-independence period and were also affected by political struggles between some nationalists and the monarchy. Consequently, it has often been challenging to differentiate between the roles of the scientist, sociology theorist, and politician in sociological profiles and actors in Morocco. A third obstacle is related to what constitutes Moroccan sociology and sociologists. The profession of sociologist has not been a prominent topic in broader discussions about culture, intellectuals, and the social sciences and humanities in Moroccan academia.

This article aims to discuss contemporary Moroccan sociology, encompassing its themes, approaches, methods, and current challenges. We begin by examining the evolution of this discipline within the Moroccan academic milieu, delineating the sociological literature that has been produced on society before, during, and after the colonial era. Although the colonial period is seen as a catalyst for the development of sociology in Morocco, a new generation of sociologists has sought to reclaim the discipline, decolonize it, and move beyond the limitations of orientalist discourse. They strive to establish a national sociology oriented towards socio-economic development and create a sociological legacy for future generations. Our second aim is to present the principal themes that inform sociological research in Morocco, the prevailing approaches and methods, and their role in the evolution of this field of inquiry. We conclude by examining some key challenges to be addressed.

The origins of Moroccan sociology

The sociological studies conducted in Morocco reflected the political debates prevalent in the country during the postcolonial era. A significant proportion of sociologists were influenced by Mohamed Guessous, a leading sociologist who was a member of the socialist party Union socialiste des forces populaires. Several strategies were developed to occupy the university space. Political rivalries turned towards sociology in the 1960s and 1970s, resulting in the closure in 1970 of the Institute of Sociology of Rabat, which had become a hub and symbol of critical thinking among university students and academics and was considered too critical and leftist by the state.

In terms of theoretical paradigms, the 1960s and 1970s were characterized by the dominance of Marxist theory. The sociology of the time sought to elucidate the functioning of society from a comprehensive standpoint. Paul Pascon’s approach to “Haouz” society, and Moroccan society in general, was characterized by holistic concepts, including social formation, mode of production, composite society, social classes, levels of social reality, and so forth. This holistic view of society was also evident in other sociological studies. Abdelkébir Khatibi produced a text on social hierarchies, while Abdellah Hammoudi employed integrated study and integrated development concepts. However, the influence of this holistic approach was gradually called into question.

Late-twentieth-century boom and the urban turn

Abdelrahman Rachik argues that the early 1990s saw a notable surge in sociological research on women, family, youth, and socialization in Morocco. This phenomenon emerged concurrently with a heightened discourse on women’s values, movements, and broader human rights concerns. The surge in research activity in these areas during this period included contributions from Moroccan researchers such as Fatima Mernisi, Aïcha Belarbi, Ghetha Al-Khayyat, Fatma Al-Zahra Azroel, Rabia al-Nasiri, Rahma Bourqia and Mohammed Talal.

Similarly, Rachik indicates that research into Moroccan urban-related topics represents another concern for Moroccan sociologists. The dominant themes in urban sociology are linked to housing (shantytowns and slums), urbanization, urban policy, real estate, and transport. In this context, the work of Françoise Buchanin, Mohammed Nasiri, Abdel Ghani Abu Hani, Mohammed Benatu, Abdelrahman Rachik, Abdullah Lahzam and Aziz al-Iraqi can be cited as illustrative examples. According to Rachik, most of these research projects have been conducted in French.

Taking up contemporary issues

Furthermore, numerous social scientists, spearheaded by Mokhtar al-Harras, Rahma Bourqia, Driss Bensaid, Ahmed Cherrak, and Abderrahim al-Atri, research the sociology of culture, the sociology of values, rural sociology, and the sociology of the family. Most of these researchers have made a notable contribution to the emergence of a new generation of Moroccan sociologists over the past two decades. The majority of these researchers conduct their research in Arabic.

Contemporary issues about religion, women, youth, and immigration are addressed by a new generation of Moroccan sociologists who use English in their research. Fadma Ait Mous, who studies collective identities and social movements, gender relations and women’s conditions, socio-political transformations, and youth and migration, is notable among these scholars. The case of Hicham Ait Mansour, who studies poverty, also illustrates Moroccan scholars’ openness to different languages and cultures. This indicates that studying Moroccan society is relevant to the global community and can reflect universal phenomena and changes. The contributions of sociological studies conducted in different languages within the Moroccan context to producing theories, paradigms, and approaches based on concrete findings are significant.

The limitations of doctoral theses

The broader domain of sociological studies in Morocco includes doctoral dissertations. These may focus on fifteen areas of research: family, organizations, space, integration and social relations, precarity and poverty, youth, education, social networks, mobility and social change, work, religion, urbanization, social history, health, and the rural world. The sociology of work, social change, development, and culture are the focus of most doctoral dissertations. However, these theses have not contributed to advancing sociological theories by introducing novel approaches or concepts. This perpetuates the methodological deficit and hinders the establishment of sociology as a separate field of research. Since they are not published, the findings of most PhD dissertations are not integrated into subsequent broader critical discussions.

Redefining sociological practices for long-term research

Despite the evident relevance of sociology to public authorities and the expectation that sociologists will contribute to the analysis of significant changes affecting Moroccan society, their involvement remains limited. This is evidenced by a bibliometric study of all social science research published between 1960 and 2006, and is due to many factors. These include limited funding, a lack of a legal framework to motivate researchers, and a lack of a specialized sociology journal. Without a public policy for scientific research, practices are essentially based on individual initiatives or individual networks, and research takes place outside the university institution. Current research into development issues (poverty, marginalization, exclusion, health, and the environment) is more responsive to political and social demands than to long-term research projects.

Sociology’s main challenge is to reconstruct itself on new foundations that will provide a new impetus for higher education and scientific production. The practice of sociology must be defined with greater precision in terms of its research orientations, within both the national and international context. In light of impending reforms, should the trend be to intensify research structures, there is a risk that these structures may become devoid of substance without a clear definition of the research objects and a commitment to scientific rigor. It is, therefore, imperative to facilitate communication between sociologists, ensure the circulation of information, and coordinate and evaluate studies to plan the discipline’s scientific future.

The policy of Arabization

A further significant challenge pertains to the linguistic issue in Morocco. Currently, sociology is taught in Arabic in all sociology departments, except in Casablanca. The process of Arabization in sociology, which can be traced back to the early 1970s, represents a broader political perspective that has implications for all social science disciplines. From this perspective, the Arabization of the human sciences can be understood as a reference to the cultural dimension of societies in the Arab–Muslim world. In the 1980s, the debate among Arab sociologists was polarized around the question of the specificity of their societies. This debate pitted those who considered that the sociology of the Arab world should contribute to a “universal” science against those for whom the human and social sciences could not claim universality. This situation has resulted in a schism in the Maghreb, particularly in Algeria and Tunisia, between Arabic-speaking and French-speaking sociologists, who pursue disparate research agendas and address distinct subject matters.

The first generation of Moroccan sociologists received their training in the Western sociological tradition, were influenced by the scientific paradigms developed in Europe, and were keen to engage in the theoretical and methodological debates of the international community. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the situation of the younger generations is a cause for concern. The Arabization policy in Morocco has not yielded the desired results. As posited by experts in the field of language studies in the Maghreb, this failure may be attributed to the initial objective of enabling Maghrebi children to become proficient in the written language of their culture, namely classical Arabic, while simultaneously acquiring proficiency in a foreign language. Nevertheless, the majority have not yet achieved either of these objectives.

As a consequence of deficiencies in language policies, these younger generations are regrettably insulated from the accumulated knowledge within their respective disciplines and from a transnational scientific field to which French-speaking Morocco had full access. Concurrently, they are re-examining methodologies that, while not inherently traditional, exhibit a certain degree of detachment from the prevailing trends in the social sciences. This discrepancy between the new generation and the sources of sociological knowledge could challenge the future of sociological practices in Morocco and integration into the scientific debates of the international community.

The challenges facing doctoral students in sociology

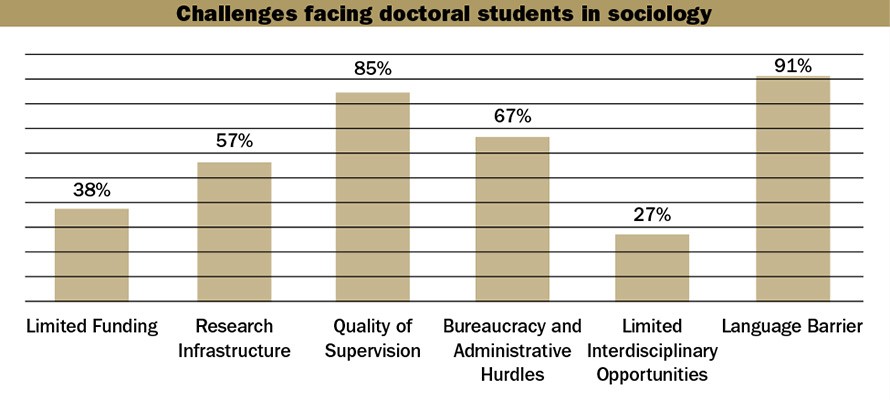

Sociology in Morocco encompasses a wide range of domains that study human behavior, society, and culture. However, teaching this science in Morocco has gone through a series of stages in which politics played a crucial role, given that most of those who specialized in this field belonged to the political left. As in many other countries, doctoral sociology students in Moroccan universities face several challenges that can affect their academic and research progress (see Figure 1).

Our survey data show that sociology doctoral students face many challenges during their training. The language barrier is seen as one of the most critical challenges at 91%, followed by the quality of supervision at 85%, bureaucracy and administrative hurdles at 67%, research infrastructures at 57%, limited funding at 38%, and finally, limited interdisciplinary opportunities at 27%.

Language barriers and the quality of supervision are significant challenges that doctoral students in Morocco or any other country may face. In Morocco, doctoral programs are typically conducted in French or Arabic. The language barrier can be a significant obstacle for many students, especially those who have previously studied in another language or have limited proficiency in these languages. This can affect their ability to comprehend course materials, write research papers, and effectively communicate with their peers and supervisors.

Students pursuing research in niche areas might struggle to find a suitable supervisor. The quality of doctoral supervision can vary widely: some students may receive excellent guidance, while others may face issues such as a lack of timely feedback, limited interaction with their supervisors, or misalignment of research interests which can affect the progress and quality of their research.

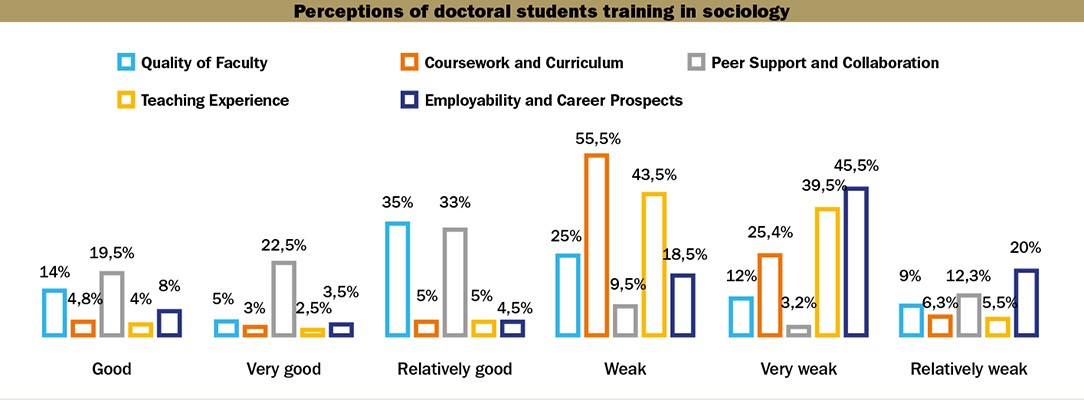

The perceptions of doctoral students training in sociology within Moroccan universities can vary depending on various factors, including the quality of faculty, curriculum, teaching experiences, and employability (see Figure 2).

Our survey data indicate negative perceptions regarding doctoral program enrollment among sociology students. Some 55% affirm that the coursework and curricula are weak, while some 45% believe that the employability and career prospects are weak. Additionally, close to 40% consider the teaching experience very weak, and a further 43% find it weak. On the other hand, 35% of the respondents consider the quality of the faculty to be relatively good, while 25% view it as weak.

In general, most students are dissatisfied with doctoral training in sociology despite the efforts made by the state in this regard. The new reform adopted by the ministry through the preparation of a new charter for theses is expected to enhance these programs in a way that serves the interests of the students and the university as a whole.

Final notes

As previously stated, Moroccan sociology has undergone substantial transformations and faced many challenges. A linguistic divide exists between sociologists writing in Arabic and those writing in French, which has resulted in a contentious field of study. A new generation of sociologists is emerging who are receptive to the use of English and endeavor to transcend the existing dichotomy between themes and interests.

Abdellatif Kidai, Mohammed V University of Rabat, Morocco <abdkidai@gmail.com>

Driss El Ghazouani, Mohammed V University of Rabat, Morocco

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: