During 2020 and 2021, I had the honor to serve as chair of the UNESCO Advisory Committee that prepared the Recommendation on Open Science draft project, approved at the 41st UNESCO Conference in November 2021. The discussions with the 30 experts who were part of the committee, representing different regions of the world, soon showed us the complexity of the idea of openness in the context of the world’s economic, technological, academic, and social inequities. The challenges of scientific openness change significantly from Global North to Global South, given the asymmetrical development of digital infrastructure, but also from West to East, within each region, and even within a country and its internal structural heterogeneity.

The most developed dimension of Open Science by the time of the preparation of the Recommendation was open access to scientific publications. Public concern for this issue seemed boosted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As noted by several studies that consider the 20-year balance since the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI), open access was born as a noble intention but evolved as a flawed reality. Vested interests within the academic publishing sector, particularly publishers of highly esteemed journals (e.g., impact factors above 10–20), had a great incentive to change their funding to a hybrid model since their subscriptions – although costly – are still coming in, and their manuscript submissions continue apace, far above their publication capacity. A dynamic drift of scholarly journals born in Open Access or mega-journals demanding increasingly high payments for article processing charges (APC) overshadowed the achievements of the Open Access movement.

In this context, one of the main concerns of all the experts who share this rich intellectual debate is how to expand scientific openness while fostering diversity and interculturality. I will introduce the conceptual discussion I recently presented at the STI Conference in Berlin as the framework for a series of mappings I made to calibrate how much we are advancing towards inclusive, open science or whether exclusion is winning the game.

The tensions between inclusive openness and exclusive closedness

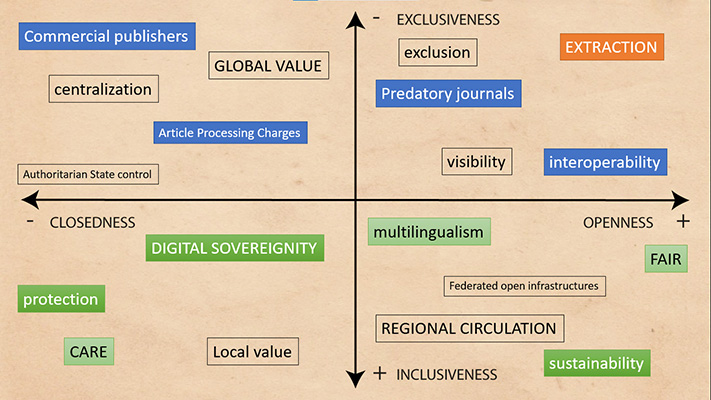

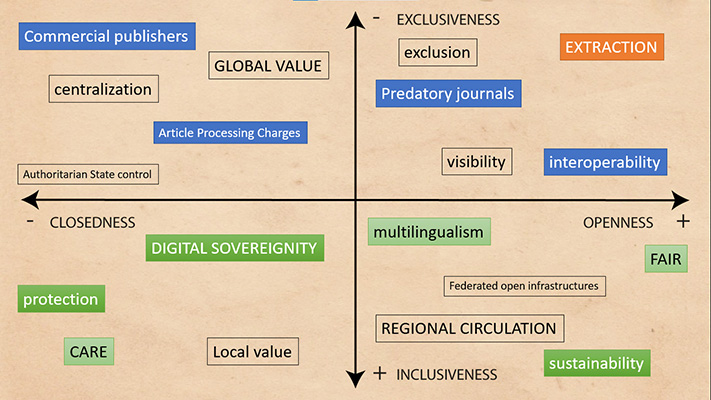

There are different paths towards open science, coexisting conflictingly at the global scale, and the tension between them is not only determined by the degrees of openness/closedness but is also related to the poles of inclusiveness/exclusiveness. Figure 1 shows different combinations in this space of conflict that are organized resembling the way Bourdieu describes the properties of a given field. We can see the features of openness to the right; and to the left, the characteristics of closedness. However, combined with the vertical axis and reading more practically from the center, where the axes cross each other, we see four quadrants. The upper quadrants feature exclusiveness, driven by commercial actors or by the traditional asymmetries of the global academic system. In the lower quadrants, on the contrary, high degrees of inclusiveness circulate, but with different limitations to openness, due to sovereignty issues or the protection required by subaltern groups.

Figure 1. The axes of inclusiveness and openness

Analyzed by quadrants, the space is organized according to opposite poles; firstly, featuring the exclusive–closedness headed by the big commercial publishers that dominate in the constellation consisting of the Scopus-Clarivate publishing platforms. The increasing concentration of scholarly services and the fact that they still control a considerable part of the credibility of the academic community makes this sector dominant in terms of global value for research assessment. Consequently, the structural bias of these global databases deepens the exclusion of a great part of the scientific results published outside high-impact journals, in languages other than English and pushing aside bibliodiversity. Contrary to inclusiveness, these commercial publishers need to offer exclusive goods and services that can guarantee access to the global value of excellence, which is (by definition) scarce and exceptional. The upper right quadrant is organized according to the main conditions for openness, such as interoperability and the other FAIR principles (findability, accessibility, and reusability). But it leads to severe exclusion within the framework of the “gold” business model where open access journals transfer the costs of publishing to individual authors that are affiliated to institutions that cannot afford Read & Publish agreements.

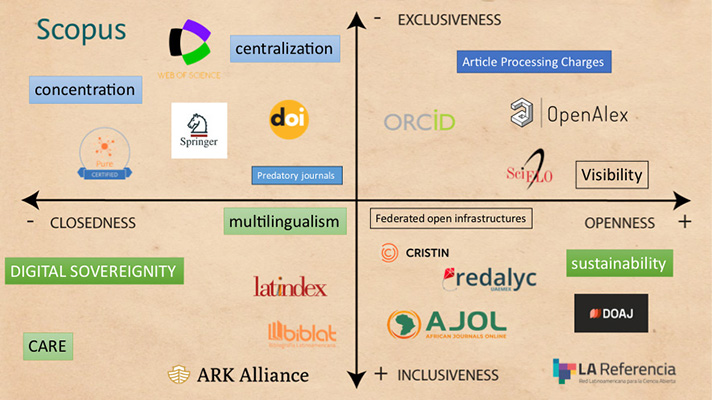

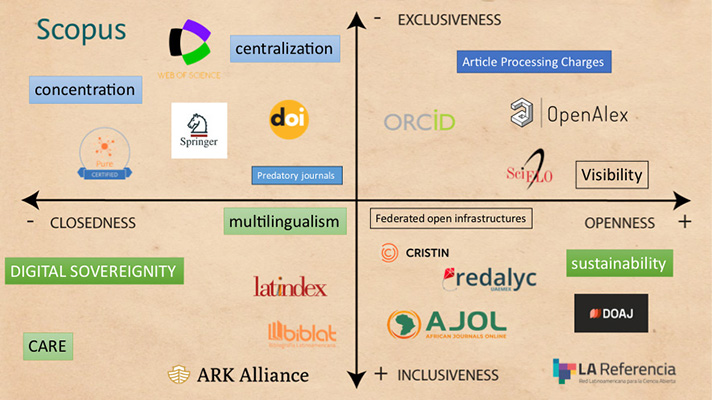

Figure 2. The field of inclusiveness and openness

Represented in the right lower quadrant in Figures 1 and 2, inclusive openness is opposed to exclusive closedness. The main drivers of this path in Open Access have been regional publishing platforms and portals such as Latindex, SciELO, Redalyc, Biblat, and AJOL, which have established conditions for quality journals in multiple languages. Given that the established hierarchies in the academic world assign little value to these journals, inclusive open science can be less visible and feature as regional circulation. However, it embodies a critical effort to preserve interculturality and foster the human right to science.

In the left lower quadrant, we see inclusive closedness: a pole featuring a restricted circulation of knowledge, which is mostly locally valued. Here, we may see scientific output disseminated in non-indexed journals, numerous initiatives for the management of scientific information and digital platforms created without permanent identifiers, and many other similar experiences. During the discussions held in the UNESCO Advisory Committee for Open Science, the risks of openness were discussed with regard to the need to protect subaltern communities, indigenous knowledge, or scientific information subject to extraction under unequal power relations: open all that is possible and close only what is necessary was the basis of the debate. However, this was critical not only to protect but also to respect the rights of indigenous groups to the autonomous government of their native knowledge. The CARE principles were born amid this tension and today represent one of the main sets of guidelines for a transition to inclusive openness: Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics.

Closedness can result from the need to protect subaltern groups or potentially extractive scientific information and can be used by state governments to defend digital sovereignty. From a democratic perspective, governments may need to protect citizens’ personal data and businesses’ economic interests in an information economy. In an authoritarian regime, in contrast, this concept has been embraced to limit academic freedom and exert social control over citizens.

As we can see, the tensions present in developing inclusive open science do not only revolve around national open science policies, unequal material resources, or commercial interests. Data governance plays a key role in contested global projects regarding the integration of digital platforms. Deep debates surround the benefits or disadvantages of centralized open infrastructures, while a more inclusive and democratic route seems to emerge from the idea of federated infrastructures.

The stakeholders in the dynamics of inclusiveness and exclusiveness

Any path to inclusive openness has to surmount two structural obstacles, one dependent on material resources and the other on the symbolic capital at stake in scientific practice. The first obstacle consists of the global inequalities forged by the digital divide and the risks of extraction that openness creates for non-hegemonic research communities lacking the indispensable infrastructures for visibility and recognition. The second emerges from the increasing struggles between commercialization and decommercialization of scholarly publishing and scientific information. These conflicts go beyond the tension of the “diamond” versus the “gold” route, given that recognition and differentiation among scientists were built under an excellence regime designed by commercial publishers. Accordingly, the feasibility of a real change is ultimately linked to addressing asymmetries with multi-causal factors.

Latin America represents an alternative open-access publishing circuit, with diamond journals that are community-managed and driven by the principle of science as a common good. However, the “mainstream” circuit still holds most of the belief of internationalized researchers in the performative effects of high-impact journals, which prevents them from changing their paths of circulation at the risk of losing recognition. SciELO, Redalyc and Latindex have made enormous efforts to increase their visibility and impact, and governmental agencies and public institutions sustain this regional circuit. However, the academic evaluation defined by these same organizations depreciates these journals, resulting in a form of alienation that still remains unresolved.

Inclusiveness faces strong forces of exclusiveness driven by oligopoly commercial stakeholders that seek to concentrate profitable goods and centralize infrastructures under closed ecosystems. Figure 3 shows some examples of such companies in the upper left quadrant. Meanwhile, in the right upper quadrant, fully open infrastructures that comply with the FAIR principles, such as OpenAlex, guarantee visibility but are limited in terms of inclusiveness by the availability of persistent identifiers (PIDs) such as DOI, ORCID, or others.

In the lower quadrants of this contested field, we can see a reinforcement of the idea that inclusiveness is highly linked to multilingualism and the interculturality of science. However, some inclusive publishing platforms have limitations regarding the availability of metadata at the level of the documents indexed in their services, and the lack of PIDs also diminishes the visibility of this quality indexed production. Autonomous governance may clash with unrestricted openness as we move to full compliance with the CARE principles, high inclusiveness of subaltern groups, and the protection of indigenous knowledge. Digital sovereignty may, for its part, imply certain degrees of closedness.

Figure 3. Positioning of commercial stakeholders and practices within the contested field

The right lower quadrant agglutinates the best examples of inclusive openness. Latin American publishing platforms and repositories are relevant stakeholders on the path toward an equitable research system. Their main strength resides in governments’ public investment in infrastructure under a general agreement on the definition of science as a common good. It is a heterogeneous region with diverse scientific policies and governance approaches to scientific information systems that coexist in a noncommercial publishing ecosystem. The relevant experience in federated infrastructures such as LA Referencia and its local technology gives the region a critical role in a just transition to inclusive open science.

These conceptual and practical tensions exist while a severe change is occurring behind the expansion of mega-journals and the pledge for fast-track peer review that blur the original interaction between a given scholarly community and the specific audience of a journal. The homogenization and automatization of editorial management displace editors from leading academic decisions. A potential crisis of legitimacy seems to emerge from the pervasive effects of commercial open access, leaving us facing a potential opportunity. I believe a radical change is only possible through a deep critique of the concept of “excellence” within contextualized and “situated” reforms in research assessment systems. Indeed, to seek inclusive openness entails new definitions of research quality, framed by the multilingual horizon of science as an intercultural common good.

Fernanda Beigel, CONICET and Centro de Estudios de Circulación del Conocimiento, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Argentina <fernandabeigel@gmail.com>