As noted by Mirowski and Sent, the “commercialization of science” is a heterogeneous phenomenon that defies simple definition, which makes many contemporary discussions of it unsatisfying. This unfortunate state of affairs is due primarily to the definition of science itself, which ranges from science as an established body of knowledge or science as an institution, to science as a process or science as the product of that process. Therefore, the question posed by the title of this article has many dimensions and lends itself to a multifaceted approach. The approach presented here, which is inevitably partial and incomplete, focuses on commercialization as a common thread.

A historical glimpse

Historical records show that trade was an important driving force in knowledge production, use, and dissemination even before science was conceived or named as such. In particular, the development of science as a European construct benefited greatly from knowledge from distant territories, either through navigation, colonization, or conquest. Once decontextualized, this knowledge became part of the scientific corpus and, more importantly, a source of economic gain. The trade in spices, medicinal plants, and other natural products from the tropical South has contributed significantly to Europe’s economic power over the centuries.

Historical records also show that knowledge has been produced and shared worldwide over the centuries. One illustrative example is the knowledge network relationships established by the Jewish Portuguese physician Garcia da Orta, who became famous for his extensive work on the medical use of Asian fruits and herbs, first published in Goa in 1563. Indeed, the connections Garcia da Orta made with Indian, Arab, Persian, and Turkish court physicians and with travelers who sailed to China, Indonesia, and along the East African coast were a great source of information. But Garcia da Orta was also a man of business, promoting the sale of medicinal plants and precious stones and their export to Europe. The 59 chapters of his complex and voluminous work were translated and circulated in abridged form in Europe, focusing on the selection of the most useful species for medicinal and commercial purposes. Not surprisingly, since the nineteenth century, he has been portrayed as a “great man of science” and a “pioneer of tropical medicine.”

The circulation of knowledge from the South to the North has not stopped since the voyages of discovery and conquest of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This has also led to commercialization of the products of such knowledge, detached from their original roots.

The creation of the funding machine

The historical asymmetries in the circulation of knowledge are still with us. In the age of globalization, we all, in the North and the South, contribute in varying degrees to science as we know it today: a politically and economically legitimized body of knowledge nourished by a growing international community of established practitioners. But asymmetries persist: contributions to science from the South have a low commercial value and are of little interest to the market. On the one hand, the products of our science are rarely used in applications of economic value in our own countries; on the other, they are largely ignored by practitioners in the North.

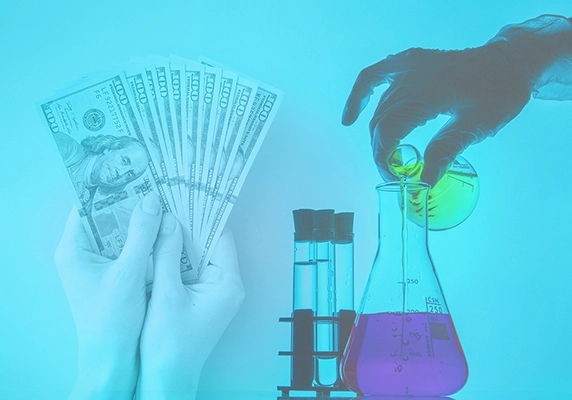

In short, our science is largely subservient to a system with the power, money, and means to decide which science “matters”: a system deeply influenced by post-World War II industrial management principles inspired by Taylorist efficiency models. The commodification of science products, scientific publishing, and its main “currency”, the impact factor, are natural consequences of the industrialization of the scientific enterprise.

Let us recall that the commercial publishing model emerged when private companies took over the journal-based publications of the learned societies, which were still the leading publishers in the first half of the last century. Those societies handed over the editorial and administrative management to commercial publishers, occasionally receiving in return renumeration to support the societies’ activities. Publishers saw the market value of this opportunity for a profitable business model, a “perpetual funding machine” in the words of Robert Maxwell, and came up with an ambitious arrangement. Accordingly, scientists would do all the substantive work, not just producing the content – the raw material – but also serving as editors and reviewing other authors' manuscripts. More recently, this was extended to all the typing and formatting of the manuscripts, which had to be delivered “camera-ready” before the Internet era, are now delivered “upload-ready” to the journal platform. What more could the publishing industry ask for?

A glimpse of the present

There was indeed more to come. The commercialization of research production has been accompanied by the creation of bibliometric and scientometric services and their promotion as indicators of “good performance” (of both individuals and institutions). This has contributed to the continuous expansion of scientific activity since the end of the Second World War.

However, this expansion, driven by business and focused on productivity, has not been accompanied by a corresponding increase in the quality and relevance of science; some analysts even speak of the stagnation of science. This is particularly true of the fundamental frontier research that underpins applications within and beyond science, as well as modern technologies. Moreover, the market created by bibliometric incentives, combined with the adoption of the Open Access “gold” model, has allowed a handful of large companies to form a transnational oligopoly responsible for around 75% of published papers. These companies now enter into commercial agreements at the institutional or national level, at prices that are increasing year by year beyond the rate of inflation and the budgetary possibilities of academic institutions. This results in a significant drain on public finances.

It is important to understand that the emergence of these large for-profit publishing corporations is not a failure of the hegemonic system of science, but an alternative that the system itself has strengthened to maintain its hegemonic status. If we are looking for someone to blame, we should focus on the market-dominated system that has penetrated and subverted nearly all areas of human activity, especially human creation. How else can we understand that, in art, a young US-Chinese entrepreneur pays 6.2 million US dollars for an “artwork” consisting of a banana fixed to the wall, only to eat it at a press conference to “make history”?

Knowledge as a public good

In their analysis of the new characteristics of capitalism, Hardt and Negri show how the commons – that which belongs to humanity as a whole – have been enclosed by the market and financial systems. The commons are the air, water, the fruits of the earth, and all that nature provides us with; but also the results of social production, such as knowledge, languages, and information. As these latter resources are socially produced, they belong to all of us; and yet, due to their commodification, the vast majority of the population cannot access them.

Scientific knowledge is a public good insofar as greater access does not diminish its value for anyone; on the contrary, it enriches us. In principle, it is to be of high quality and trustworthy in order to generate broad public support for scientific activity and its products – although, in practice, we are far from this ideal.

When discussing the management of the commons, Elinor Ostrom does not differentiate between natural and immaterial resources, such as knowledge. In both cases, she argues that the capacity of individuals to manage resources varies depending on the possibilities and willingness of the community to govern itself by adopting a set of agreements and rules of the game.

Decommercializing science publishing to retain ownership and control dissemination

Following Ostrom’s arguments, academic communities must be willing to manage themselves; specifically, to regain control over the publication of knowledge products. In this respect, Latin America is setting a good example for the world since most of our scientific journals are published by academic not-for-profit institutions. What is needed is for public policies to correct the contradictory practice of favoring commercial publications and to prevent our scientific knowledge-producing communities, financed with nations’ public resources, from continuing to respond at the beck and call of the publishing oligopoly.

Publication free of charge for both authors and readers has been the dominant practice in Latin America since before the term “diamond” Open Access was introduced in the North and adopted in the South. It ensures that the academy retains ownership of the knowledge it generates and takes control of its dissemination, establishing the channels and ways of making it accessible.

Decommercializing science may be a tall order as it will require, among other things, a significant shift in mindsets regarding the social value and purpose of science. Decommercializing the publishing enterprise, which is part of the problem, is more realistic, although it requires concerted action by policymakers and the scientific community. Some institutions are taking initial steps in the right direction by canceling subscriptions to giant for-profit publishers or changing their academic evaluation criteria. But this is only the beginning.

Ana María Cetto, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico <ana@fisica.unam.mx>