Surveillance of Gulf Migration

May 30, 2017

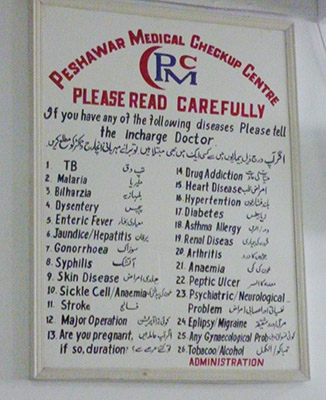

Over the past three decades, as more and more developing countries have sent their citizens overseas to work, Pakistani citizens have been recruited as laborers to the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. But to be granted a visa to the GCC, labor migrants are required to produce health certificates at the time of departure from Pakistan – certificates which can only be obtained from GCC-approved medical screening centers. Crowds of aspiring migrants throng these approved medical screening centers, located in a few big cities, where they are screened and tested for deformity or diseases. Only those bodies are selected that have no trace of a disease or infection, past or present, with no signs of physical weakness.

The GCC states have no qualms about requiring sending countries to sift through the hundreds and thousands of aspiring migrants and select only the best bodies. Countries like Pakistan, competing for Gulf remittances with its neighbors India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and regional giants like Malaysia, do not dare to object. Although Pakistan’s government prizes labor migrants as valuable economic assets because of the remittances they send – describing them as informal ambassadors who carry a moral responsibility to remain true to their Muslim and Pakistani identity – Pakistani citizens in the GCC receive little meaningful support from their country’s diplomatic missions, which are anxious to increase Pakistan’s visa quota.

Stories of irregularities at these centers and malpractice in the screening process abound. Most of these stories convey a sense of exploitation of the aspiring migrants, their frustration with screening results, which are often proved wrong by other private or government laboratories, and a sense of abandonment by the state into the hands of the businesses who declare them “fit” or “unfit” for migration.

Together, the centers form a strong cartel, with regional and central Gulf Approved Medical Centers Associations which look after the business interests of each of their members by maintaining a monopoly over the screening process, disallowing competition between members by equally distributing the numbers, and protecting center staff against possible attacks from individuals declared medically “unfit” for migration or attempts by Pakistan’s government departments to regulate them. Screening standards are set by the GCC secretariat in Saudi Arabia and the conditions of the screening centers – the laboratory equipment, space and personnel – are also supposed to be monitored by the GCC secretariat through annual inspections.

Unlike the classic examples of medical screening of migrants at the point of entry, as at Ellis Island and Angel Island in the United States, the screening of Pakistani labor migrants to the GCC takes place in Pakistan itself. And while this form of medical screening is less visible than the often-criticized testing processes used at places like Ellis Island, this form of medical screening is equally invasive.

Afraid of failing to pass these screening processes, some aspiring labor migrants fall into the hands of exploitative hustlers who have (or claim to have) connections with those working inside the screening centers. Others, who fail to obtain health certificates even through these informal means, try different channels of migration, often falling into the trap of illegal land, air and sea migration.

Even after obtaining a clean bill of health – sometimes after several rounds of testing and at great financial cost – another round of medical screening is required when the migrant arrives in the Gulf region. Any workers who fail this last test are sent back. If they are allowed to enter the GCC, they must undergo annual comprehensive medical screening to renew their permission to stay.

Ironically, epidemiological evidence suggests that migrants often develop infections like TB and HIV during their stay within the destination countries – as testified by policies of compulsory annual testing as a precondition for the renewal of work permits in the GCC, because of the arduous conditions of transit and labor they find themselves in. For example, in the case of HIV transmission, it is because of the lack of economic and cultural citizenship which leaves them living in cramped labor camps and with few ways to enjoy pleasures other than going to sex workers.

Anyone identified as HIV positive at any stage is detained and deported, often without informing the individuals or their country’s diplomatic mission of the actual reason for deportation. Some workers have been sent back on “surprise leave” by their employers, and are never recalled; some of these returnees have not been allowed to collect their belongings, settle their affairs with co-residents/workers or even collect their passports and outstanding wages from employers before being whisked away to crowded detention centers. Many arrive in Pakistan with only a one-page Emergency Passport as proof of identity; some are then detained by immigration authorities to confirm their Pakistani citizenship, a process that can last for weeks, ending only when family members find a local patron to secure their son’s release.

The world is seeing more and more protests over “health citizenship” rights, as people call on governments to provide access to health care and challenge the insidious ways in which medical practices and diagnoses have been used to limit the rights of individuals. In Pakistan, however, labor migrants have not shown any signs that they are ready to mobilize or engage in this type of collective action, and the government continues to cooperate with the GCC states by letting their agents line up potential migrants like cattle, to be sorted through on the basis of their health.

Ayaz Qureshi, Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan <ayaz.qureshi@lums.edu.pk>