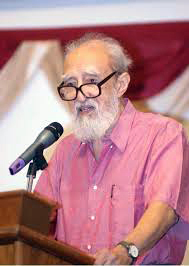

Read more about Social Science in Malaysia

The Life and Times of a Committed Sociologist An Interview with Dato Rahman Embong

by Michael Burawoy and Rahman Embong

August 17, 2013

Long before they were officially introduced as university subjects with their own academic departments, anthropology and sociology contributed to the construction of the colonial knowledge that informed the idea of Malaya and, after 1963, of Malaysia.

During the colonial era, colonial knowledge provided the “define and rule” framework to govern, which, in turn, justified the implementation of the “divide and rule” principle in the day-to-day running of the state. The Royal Society of Great Britain and Ireland, established in 1823, was the main vehicle for social science to enrich colonial knowledge and the technology of rule in Malaya and then Malaysia. It had a branch in the Straits Settlement of Malaya and Borneo, established in 1878, and run by the British East India Company from Calcutta. The Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society had its Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (JSBRAS). In 1923, it was renamed the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (JMBRAS) and, in 1964, it became the Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (JMBRAS). The Society also published its own MBRAS Monographs.

For around 135 years, the idea of Malaysia was shaped through the Society’s publications, whose content included materials on history, geography, literature, language, culture, community studies, botany, and zoology. The main contributors were mainly colonial civil servants who were mostly trained in anthropology (Diploma of Anthropology) in Oxford, Cambridge, or London before being posted to Malaya. John Gullick (1916-2012) was one such officer, who served in Malaya and wrote at least a dozen books on Malaysian history and society, framed as historical sociology. Many of these were later adopted as textbooks in local universities.

It is no surprise, therefore, that after the Second World War, the first researchers sent by the Colonial Office to Malaya were two world-famous academicians, the social anthropologists Raymond Firth, who came to study the state of social science research in Malaya, and Edmund Leach, who came to study the socio-economic condition of the society in Malaya and Sarawak. Firth and Leach were followed by their students who conducted extensive fieldwork in the early 1950s in Sarawak focusing on the Chinese and the indigenous groups, in Singapore examining the cultural habits of the Malays and Chinese, and in Negeri Sembilan on the only matrilineal society in Malaya, and in Johor on the impact of the Kiyai Salleh millenarian movement on Sino-Malay relations. They produced a collection of high-quality monographs published in the UK and elsewhere.

The next generation of students to study under Firth in London included Abdul Kahar Bador (who studied Malay traditional leaders), Mokhzani Rahim (the Malay credit system) and Syed Husin Ali (Malay peasantry and leadership). They all returned to teach at the University of Malaya (UM) where they were joined by the Amsterdam-trained sociologist, Syed Hussein Alatas, famous for his book The Myth of the Lazy Native (1977), which contributed to the ideas of Edward Said’s Orientalism. These scholars formed the nucleus of the teaching and research of anthropology and sociology.

In the aftermath of the ethnic riot of May 13, 1969, the four above-mentioned social anthropologists played an important public role in the “healing process” through their participation in the activities of the National Consultative Council, bringing peace and stability in the country. A Ford Foundation Report, entitled Social Science Research for National Unity: A Confidential Report to the Government of Malaysia (1970), adopted by the government, led to the introduction of anthropology, sociology, political science, psychology, and communication studies as university teaching subjects, which would lay the basis for the Malaysian Association of Social Sciences, established in 1978.

The government also established a Department of National Unity, in July 1969, very soon after the ethnic riot. Many of its directors and officers were anthropologists and sociologists who had graduated from the new departments and from the older Department of Malay Studies at UM. Indeed, until the 1980s, many top civil servants in Malaysia were graduates of these same departments.

The first batch of anthropologists and sociologists graduated from UM and UKM in 1974 and 1975, respectively. They were well received both in the public and private sectors, where they readily found employment as much-needed “generalists,” who could make sense of contemporary issues and serve their clients. Their ability “to peddle culture” in multi-ethnic and culturally diverse Malaysia was in high demand, which continued into the 21st century. A Malaysian lecturer in anthropology, Tan Chee Beng, who edited the Bibliography of Ethnic Relations in Malaysia (1999), made particularly important contributions to the study of ethnic relations. In 2005, the Malaysian Cabinet mooted the introduction of a compulsory “Ethnic Relations Course” for all students enrolled in the twenty public universities in Malaysia. The module for the course was prepared by a team led by myself and in 2007 I was entrusted with the establishment of a full-fledged Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA) at UKM.

In short, anthropologists and sociologists have played a critical role in the making of Malaysia, in particular, helping to maintain social cohesion. They remain the quiet achievers indispensable to the “Idea of Malaysia,” a plural society, ethnically complex, yet in a state of stable tension unusual in such societies today.

by A.B. Shamsul, The National University of Malaysia (UKM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: