Read more about Real Utopias

Confronting Water Injustice

by José Esteban Castro

Development as Justice: A Real Utopia from India

by Kalpana Kannabiran

July 18, 2011

Erik Wright is President-Elect of the American Sociological Association and the theme of his Presidency will be “envisioning real utopias,” which is also the title of his latest book. I assigned him the task of explaining in less than 1500 words what he means by real utopias and what is their relevance for global sociology. Do you think he passed?

The idea of real utopia is rooted in what might be termed the foundational claim of all forms of critical sociology: we live in a world in which many forms of human suffering and many deficits in human flourishing are the result of the way our social structures and institutions are organized. Poverty in the midst of plenty does not reflect some unalterable law of nature; it is the result of the way the existing social organization of power and inequality massively affects the possibilities for human flourishing. This foundational claim suggests three central tasks for a critical sociology: first, the diagnosis of the social causes of these harms; second, the elaboration of alternative institutions and structures; and third, the development of a theory of transformation which tells us how to get from here to there. The study of real utopias is one way of approaching the second of these tasks.

The utopia in “real utopia” means thinking about alternatives to dominant institutions in ways that embody our deepest aspirations for a just and human world. This is fundamentally a moral issue: figuring out the moral standards by which institutions should be judged and exploring how alternative institutional arrangements might more fully realize those values. The real in “real utopia” also explores alternatives to dominant institutions, but focuses on problems of unintended consequences and self-destructive dynamics. What we need are clear-headed, rigorous models of viable alternatives to existing social institutions that both embody our deepest aspirations for human flourishing and also take seriously the problem of the practical design of workable institutions – and thus are attentive to what it takes to bring those aspirations to the real world.

Exploring real utopias implies developing a sociology of the possible, not just of the actual. But how can we do this without falling into idle armchair speculation? One of the most fruitful strategies is to identify actually existing social settings that violate the basic logics of dominant institutions in ways that embody emancipatory aspirations and prefigure broader utopian alternatives. The task of research is to see how these cases work and identify the ways in which they facilitate human flourishing; to analyze their limitations, dilemmas and unintended consequences; and to understand ways of developing their potentials and enlarging their reach. The temptation in such research is to be a cheerleader, uncritically extolling the virtues of promising experiments. The danger is to be a cynic, seeing the flaws as the only reality and the potential as an illusion.

The study of inspiring empirical cases, however, is only part of the agenda of real utopias. Focusing exclusively on empirical cases tends to narrow the conception of alternatives to specific kinds of institutions, often at a fairly micro-level of social organization. We also need an understanding that “another world is possible” at the macro-level of the functioning of social systems as a whole. In the past that kind of discussion revolved around the epochal contrast between capitalism and socialism. To explore this kind of system-level alternative requires more abstract theoretical analysis of different models of social and economic structures. A fully developed sociology of real utopias integrates the concrete empirical investigation of institutions that prefigure emancipatory alternatives with such abstract theoretical discussions of the principles underlying alternative systems.

In this short essay there is not space to elaborate this full agenda. What we can do is put some flesh on the bare-bones idea of studying real utopias by examining two illustrative empirical cases. Each of these cases embodies, if still in partial and incomplete ways, the utopian vision of radical, democratic egalitarian alternatives to existing institutions. The first comes from the Global South; the second from the Global North.

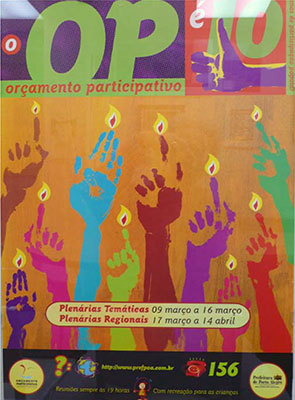

Urban Participatory Budgeting

The idea of a ‘direct democracy’ in which citizens personally participate in making democratic decisions within a political assembly seems, to most people, hopelessly impractical in a complex modern society. The development of what has come to be known as ‘participatory budgeting’ is a sharp, real utopian challenge to that conventional wisdom. Here is the basic story: Participatory budgeting was introduced almost by accident in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1989. Porto Alegre is a city of around one and a half million inhabitants in the south-east corner of the country. In late 1988, after long years of military dictatorship and a period of transition to democracy, a left-wing party won the mayoral election in the city but did not control the city council, and thus faced the prospect of having four years in office without being able to do much to advance its progressive political program.

Faced with this situation, the activists in the party asked the classic question, what is to be done? Their answer was a remarkable institutional innovation: the participatory budget, a novel budget-making system anchored in the direct participation of ordinary citizens. Instead of the budget being formulated from the top down, Porto Alegre is divided into regions each of which has a participatory budget assembly. There are also a number of city-wide budget assemblies on various themes of interest to the entire municipality – cultural festivals, for example, or public transportation. The mandate for each of these participatory budget assemblies is to formulate concrete budget proposals, particularly for infrastructure projects of one sort or another. Any resident of the city can participate in these assemblies and vote on the proposals. After ratifying these regional and thematic budgets, the assemblies choose delegates to participate in a city-wide budget council for a few months until a coherent, consolidated city budget is adopted.

The participatory budget has been functioning effectively in Porto Alegre since the early 1990s. In some years the budget process is vibrant, actively involving thousands of residents in city budget deliberations; in other years, especially when discretionary spending is limited, participation declines. By all accounts the participatory budget has contributed to invigorating public involvement in city affairs and redirecting city spending towards the needs of the poor and disadvantaged rather than of elites. Overall, then, the participatory budget has opened a space for an expansion and deepening of democracy beyond the limits of what had been thought possible.

In the years since the invention of the participatory budget in Porto Alegre, there have been over 1000 cities around the world in which some form of participatory budgeting has been tried. This is an instance in which a real utopia innovation in the Global South has migrated to the developed regions of the world.

Wikipedia

Imagine that in 2000, before Wikipedia existed, someone proposed to produce, within ten years, an encyclopedia with about 3.5 million English entries which would be of sufficient quality that it would become the first place to which millions of people would turn to get basic information on a very wide range of topics. Then suppose that this person proposed the following institutional design for producing and distributing the encyclopedia: (1) the entries would be written and edited by hundreds of thousands of people around the world without pay; (2) anyone could be an editor and anyone could edit any entry in the encyclopedia; (3) access to the encyclopedia would be free to anyone in the world. Impossible! To imagine hundreds of thousands of people cooperating to produce a fairly high quality encyclopedia without pay and then distributing it at no charge flies in the face of economic theory that insists such widespread cooperation needs monetary incentives and hierarchy in order to be effective. Wikipedia is a profoundly egalitarian, anti-capitalist way of producing and sharing knowledge. It is based on the communist principle “to each according to need, from each according to ability.” It is organized on the central principles of horizontal reciprocities rather than hierarchical control. And, in less than a decade, is has basically destroyed the commercial market in encyclopedias that had existed since the 18th century.

Wikipedia is the most familiar example of a new form of noncapitalist, nonmarket production that has emerged in the digital age: peer-to-peer, collaborative, noncommercial production. These new forms of production, in turn, are closely connected to a number of other real utopian dimensions of the information economy, such as the creative commons, copyleft licensing, and open-source software. What remains to be seen, of course, is the extent to which these new forms will be corrosive of conventional capitalist forms of intellectual property rights, or simply increase the diversity of economic forms within a dominant capitalist economy.

These two examples illustrate the basic idea of social alternatives that run counter to the dominant ways of organizing power and inequality in contemporary institutions. These – and many other – examples open up new spaces for more egalitarian and democratic forms of social interaction. They reflect utopian aspirations for transformed conditions for human flourishing, yet they also seek ways of embodying those aspirations in real institutions. Understanding such possibilities is the point of the real utopias agenda.

Erik Olin Wright, University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: