Read more about Notes from the Field

Enduring the Waves: The Life and Work of a modern-day Seafarer

by Helen Sampson

China in Africa

by Ching Kwan Lee

October 25, 2013

There were ten massacres in Puerto Rico in 2012. As of May 2013, the massacre-counting news media has reported a total of six massacres in this US Caribbean possession of 3.7 million inhabitants.

While in 2011 Puerto Rico obtained an unflattering position in the United Nations’ Global Study of Homicide and its murder rate made headlines in the New York Times, the fact that there have been sixteen massacres over a period of sixteen months has not received international attention. While I am not advocating for statistics of violence to be the measure of the island’s international recognition, it strikes me that one single massacre in a movie theater in Colorado receives more news coverage than one island virtually experiencing monthly massacres.

Even with the often morbid attention to violence by global news networks, the pattern of events in Puerto Rico is not “breaking news.” Their focus is on one-off events and on the West –and not the rest. But another reason why this otherwise shocking string of massacres has not caught the attention of news organizations or of sociologists may have to do with numbers and naming. It only takes three fatal victims for a violent incident to be named a massacre by the Puerto Rican media.

At the local level, the practice of naming massacres after they reach the third victim seems to be unquestioned. It is allegedly the measure used by the police for categorizing these incidents, and yet, when the Police Superintendent qualified one of them as an “incident where there are multiple victims” without using the word massacre, local criminologists chided him. One criminal justice professor justified using the word because “be it due to custom or norm, this type of terminology is applied for cases with three or more victims.”

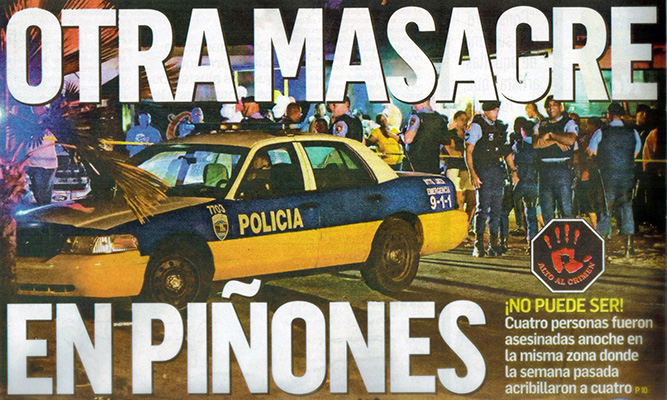

But within a global comparative framework, or when Puerto Rican news media report on massacres elsewhere, the local use of the word can be problematic. For example, Puerto Rican newspapers have used the front page capital letter headline “MASACRE” for two qualitatively different incidents: the local one was the killing of four persons in a car-to-car shooting and the international one was Anders Breivik’s shooting of 69 persons in Norway. Clearly, the conflation of different types of violence under the same name precludes our understanding of both incidents and of violence in general.

Writing on massacres, Jacques Semelin maintained that “sociology has neglected this field of study for far too long, leaving it to the historians.” Indeed, historians, and also social psychologists, have contributed greatly to our understanding of collective violence, but with the focus on genocides. The sociological literature includes Charles Tilly who examined varieties of collective violence, but without conceptualizing the massacre. Wolfgang Sofsky and Semelin have both outlined specific ingredients for a massacre to have taken place, and the latter has defined it as “a form of action that is most often collective and aimed at destroying non-combatants.” Yet, no one establishes how many victims constitute a massacre. The one definition that refers to “three or more people” is that of the Guatemalan Human Rights Commission, but only if other characteristics have been met (namely, the intention of eliminating the opposition, create terror, cruel and degrading treatment of victims, and systematic perpetration).

We are back to square one, without being able to ascertain whether the Puerto Rican killings-of-three are in fact massacres. Elements in the definitions above, and also the fact that Semelin seems to conceive of the massacre as an act that is part of – or happens en route to – the genocide (which then includes the element of total elimination), raise the question of intention in our analytical approach to massacres and their perpetrators – be it the killing of three in Puerto Rico or that of dozens elsewhere. Does a car-to-car quick execution with a machine gun between opposite drug-trafficking gangs meet the degrading criteria? Was Breivik’s main intention the total elimination of members of the Norwegian Labour Party? Did Adam Lanza target a specific group (ethnic or otherwise) in Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut?

As sociologists we certainly need to make a more profound analysis of the large middle terrain that exists between individual acts of violence and genocides, for here is where the massacre as social phenomenon exists. Some may argue that once we know what happened in any given deadly incident of collective violence (say, the 2012 killings in Houla villages in Syria), it doesn’t matter whether we name it a massacre or not. Well, we may know what happened, but we will not understand why and how it happened. Naming something after the first word in the catalogue of unthinkable acts of violence should not be an easy way out from the process of understanding.

Moreover, if we take from Pierre Bourdieu the idea that by naming things we create them, we may in fact end up – at least in Puerto Rico – with massacres defined only on the basis of numbers (as three or more victims) without regard to other important sociological criteria. This is not irrelevant. In recent years, Puerto Rico has been immersed in a profound debate about the death penalty, most recently triggered by a Federal Court trial against the perpetrator of a massacre in 2009. Among those making public statements, one local politician favored capital punishment for the “authors of massacres,” presumably defined in Puerto Rican style. It may not be long before the island witnesses another trial for a massacre, one in which the very definition of the word might be on trial. “Legal discourse,” Bourdieu states, “is a creative speech which brings into existence that which it utters.” If massacres can legally become any killing of three victims through the definition by the media or some politicians, and if the death penalty becomes the punishment for its perpetrators, it may be time for sociologists to engage in a more elaborate conceptualization of mass killings and massacres.

Jorge L. Giovannetti, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: