Read more about Notes from the Field

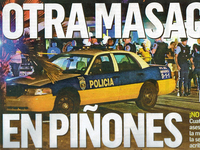

Puerto Rico: An Island of Massacres?

by Jorge L. Giovannetti

Enduring the Waves: The Life and Work of a modern-day Seafarer

by Helen Sampson

October 25, 2013

Dear Michael, Greetings from Kitwe!

Yes, here I am doing ethnographic fieldwork in your old stomping ground – the Zambian Copperbelt. This month, I am based at the Nkana mine, which local residents assure me was once upon a time called “Rhokana” – the mine where you did your own research 40 years ago for The Colour of Class. Now I have ended up in the exact same spot. As you may know, under pressure from the IMF, the Zambian government was forced to privatize the copper mines, beginning in 1997. Nkana was “bundled” together with Mufulira, and sold to Glencore, the notoriously storied and powerful commodity trader based in Switzerland. The mining house is now called Mopani Copper Mines.

Those bungalows near the mine shaft may well be the ones you inhabited. They are now offices for management, engineers, and geologists. Skirting the mine are several high-density residential compounds where many miners live, amidst open sewage, mostly without electricity and with only communal water taps. My heart sinks every time I see small, barefooted children roaming the roadsides littered with debris and broken beer bottles. I cannot but wonder if you left Zambia at its most hopeful and confident moment, right before it began a steady decent into four decades of stagnation, even involution. It has only been since around 2004, when world copper prices made a strong recovery, fueled by voracious demands from China and India, that people saw signs of economic revival. But even now, joblessness and poverty are still pervasive.

I started visiting Zambia five years ago following Chinese capitalism to Africa. As a student of Chinese labor for almost twenty years, I was intrigued by the barrage of critical reports in the Western media on “Chinese labor exploitation,” stories that always ended with an ineluctable specter of “Chinese neo-colonialism.” Indeed, Chinese signs are everywhere on the Copperbelt, announcing the arrival of the Bank of China, the contractors rehabilitating roads, erecting the sleek bird’s nest-shaped Ndola stadium, and building the infrastructure for the newly commissioned Zambia-China Economic Cooperation Zone, anchored by the Chinese state-owned Chambishi Copper Mine and the Chambishi Copper Smelter.

But soon after I arrived, I realized the Chinese presence is only part of a broader influx of international capital on the Copperbelt. The largest mining house here, Konkola Copper Mines, is owned by Vedanta, a London-listed multinational corporation hailing from India. One of the biggest mining corporations in the world, the Brazilian Vale, has recently acquired the Lubambe mine, and the South African First Quantum Minerals Limited is running the open pit mine in Kansanshi, by far the most profitable. Together with the Swiss-owned Mopani, it is easy to see how privatization of the Copperbelt has turned this area into a natural site for comparative sociology. I came with a puzzle: what is the peculiarity of Chinese capital in Africa? I am hoping that a double comparison – between Chinese and non-Chinese companies and between construction and mining – will allow me to specify the interests, capacities, and practices of the Chinese companies that distinguish them as “Chinese” rather than simply “capitalist.”

A cursory comparison between our different modes of entry into the field points to some of the sea changes in the Zambian political economy during the 40 years that separate our projects. Then as now, foreign capital is a powerful player. I always thought of them as gated kingdoms shrouded by layers of security checks and proprietary claims on company information. Through personal connections, you broke into this world as a full-time employee in the personnel research unit that serviced the two mining companies of the time – Anglo American Corporation and Roan Selection Trust. I tried pursuing a similar route, but my job interview with the secretary of the Chinese Communist Party at the Chinese smelter ended disastrously. The party boss did what a 21st-century manager would do – he “googled” me, and was horrified to see my work on labor protests in China and Zambia. After lecturing me about how the global discourse on “China’s scramble for Africa” is just the latest instance of China being humiliated by the imperialist West, he sent me packing. I had no choice but to “defect” to the other side. With a stroke of providential luck – and all field workers have to get lucky at some point – I became friends with a Zambian opposition politician who had taken an interest in a paper I wrote on China in Zambia. Consoling me after my failed job interview, he said, “Wait until we are in power.” I did – his party won in the 2011 election! As the Vice-President of the Republic, he called up the CEOs of the major mines, and ushered me in as a Zambian Government Consultant.

This vignette underscores perhaps a significant realignment of interests between an African state and multinational mines. It reminds me of the necessity to take seriously the interest and agency of the Zambian state, and not to assume its powerlessness. Influenced by Frantz Fanon, your argument in The Colour of Class was that political independence without structural economic change could not bring about an autonomous nation state or an effective national bourgeoisie. But today, the single party regime of Zambia’s First Republic has been replaced by a competitive multi-party system since 1991, coinciding with the imposition of privatization and structural adjustment programs by the World Bank and IMF. Twenty years of neoliberalism have so exacerbated mass discontents about persistent poverty and inequality that political parties have been compelled to get tough with foreign-owned mines. In recent years, to the utter dismay and outrage of the mining companies, the Zambian Government has imposed Windfall Taxes (although later canceled), unilaterally nullified the Development Agreements used to privatize the mines, doubled the rates of mineral royalties, and is now training technocrats to conduct forensic auditing inside the mines. I see my research as part of this state effort to render the mines financially and sociologically legible. Of course, it is easier for politicians to ride the wave of “resource nationalism” – a nationalism that secures political support through dispensing the revenue from mining – than to nurture the state capacity that may generate development. Working with and within the Zambian Government only throws this into sharp and sad relief.

How will the Chinese and non-Chinese foreign investors navigate and orchestrate this new African reality? I will have to write a book rather than a greeting note to answer that. This is just a prologue to a global dialogue of the future.

Ching Kwan Lee, University of California, Los Angeles, USA

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: