Read more about Michael Burawoy – Public Sociology

Pushing Public Sociology Toward Dialogical Sociology

by Sari Hanafi

Reflecting on Michael Burawoy and Public Sociology

by Margaret Abraham

October 04, 2022

In this piece, we discuss the challenges facing public sociology in today’s Russia. The underlying question we address is: What can we say of professional commitment in a political regime whose name is still to be found? We are currently living the real dystopian nightmare of the “special military operation” – the war in Ukraine – and here we describe its effects on sociology in statu nascendi. We refer to the discussions and research conducted in Russia, to our professional experience, and to Michael Burawoy’s 2021 book Public Sociology: Between Utopia and Anti-Utopia (2021), which we have discussed with colleagues, including those mentioned by Burawoy in the preface to his book and researchers who have contributed to the development of Russian public sociology.

Inspiration from Michael Burawoy

Michael Burawoy identifies several features of sociology in non-democratic regimes. He maintains that in such circumstances sociology functions as “a transmission belt for the ideology of the party-state” and exists mainly in the form of servile policy sociology. Academic freedom is limited and scholars experience rigid control over their professional activities. We consider that such a subordinate orientation to the party-state is an unwanted birthmark of sociology in Russia and adherence to this path is difficult to overcome.

However, the oppositional current of critical professional sociology and its commitment to public openness are also important in the Russian sociological landscape. While empirical sociology has generally existed in the form of directed or guided policy research, there are also sociologists who have been fighting for professional autonomy, for the right to provide independent expertise, and for the possibility of openly discussing issues within the sociological community and with the non-academic public. Russian sociologists have always striven to be public intellectuals. In the Soviet years, the best sociologists sadly complained about the merely ornamental character and the pointlessness of their research. They provided the social diagnosis and gave advice nobody listened to in the authoritarian regime.

Burawoy claims that in order “to flourish, our discipline needs public engagement.” The self-reflection of Russian sociologists confirms this statement. Debating the prospects for Russian sociologists in the 2000s, scholars agreed that “theoretical poverty” and a lack of professionalism are caused by the weakness of civil society, gaps in institutionalization and a lack of autonomy (Romanov & Yarskaya 2008; Sokolov 2009). One part of the professional community expressed hopes that democratization and integration in the global sociological community would help to overcome the limitations of shallow and servile policy sociology. Others emphasized the trend of fragmentation and a lack of professional communication (Lytkina & Yaroshenko 2019).

Achievements of public sociology in the 21st century

In post-Soviet times, the visibility of sociology in the public realm has grown. Public sociology claims have always resonated with the popular idea of our profession. New generations of Russian sociologists believe that to carry out sociological research is to engage with citizens; they conduct research targeting grassroots initiatives and NGOs. Thus, the idea of organic public sociology has gained support within the professional Russian community.

But for the most part, what we still see are the effects of traditional public sociology: public lectures, interviews, expert evaluations, popularization of research data; all these activities now count in professional ratings. Public engagement brings material and symbolic benefits to institutions and individuals. Over the last few decades, Russian sociologists have learned how to communicate with the media (by making informed choices of reliable media interlocutors). This know-how has become an achievement of traditional public sociology in Russia. For a while now, there has been a political split that has become an important feature of the sociological field in Russia. Until recently, representatives of different camps each found their own means of publicity. For critical public sociologists, there has been a reliable niche comprised of different agencies that were prepared to work with them, including The Echo of Moscow radio channel, The Novaya Gazette newspaper, and several online resources.

However, with the tightening of authoritarian rule, the public realm has gradually shrunk. Critical journalism and research, represented by both individuals and institutions, have been forced out of the official public realm. They have either been labeled as “foreign agents,” have undergone ideological transformations through self-censorship, or have simply been liquidated.

Repressive legislation, disempowerment of civil society, and suffocation of public sociology

Before the ill-fated day of February 24, 2022, when the “special military operation” in Ukraine was launched by the Russian state authorities, the autocracy successfully disempowered Russian civil society, limiting the ability of the popular classes to influence state policy. Recent persecution was made legally possible by a set of repressive laws passed by the Russian legislature after mass protests against electoral fraud in 2011-12. More specifically, the “Gay propaganda” legislation (2013) restricts the freedom of speech and criminalizes the LGBTQI+ community. It has contributed to the straightjacketing of gender studies in Russia. “The Law on Foreign Agents” (2012) has functioned as a garrote causing the asphyxia of civil society and the restriction of professional activities of non-state institutions engaged in organic public sociology projects. This law initially targeted NGOs involved in political activities and receiving international grants. Nowadays, policy and public advocacy research has become the object of such qualifications. Human rights organizations and non-governmental research institutions such as Memorial, the Levada Center, the Center for Independent Social Research, and gender studies centers were the first targets listed as foreign agents (FA). The costs of this “toxic” status are often insurmountable barriers for social research, which result in the narrowing down of international cooperation, as well as financial austerity and bureaucratic expenses (Skibo 2020).

The enforcement of the repressive laws has likewise stifled Russian civil society. Its voices have become weakened as if trying to escape from suffocating throats. Active citizens, civic initiatives and NGOs fear persecution. Public fear as well as actual repression have produced breathing difficulties for public sociology.

Most NGOs have sought to avoid stigmatizing status and have chosen the strategy of self-liquidation. (Many gender studies centers have closed.) A few “FA” NGOs have continued their activities, carrying out a self-imposed experiment in survival. Self-censorship has become another popular strategy for researchers and journalists who are trying to continue “business as usual” under stifling conditions. While the official media channels have restricted contacts with FA, social media have started to constitute an alternative public realm for open discussions and open breathing.

However, this was only the initial phase of the “special operation” against that part of Russian civil society that still remained unsilenced. The two years of the COVID-19 pandemic have helped the autocracy to prohibit public events, crush protests, and shift public attention from international affairs to health threats and personal life.

The dystopia of the special military operation and the asphyxia of public sociology

After the start of the war in Ukraine the situation has worsened drastically. A new series of repressive laws has closed down public discussion and criminalized protests. The 2022 amendments to the FA Law extend the range of targets and pretexts for persecution. The new statuses of “undesirable organization” and “unfriendly country” smash efforts towards international academic cooperation. In this context, adepts of public sociology are easily categorized as foreign agents and forced to join the ranks of the persecuted. This can even happen to those researchers and institutions who try to demonstrate their apolitical standpoint and their belief in academic neutrality.

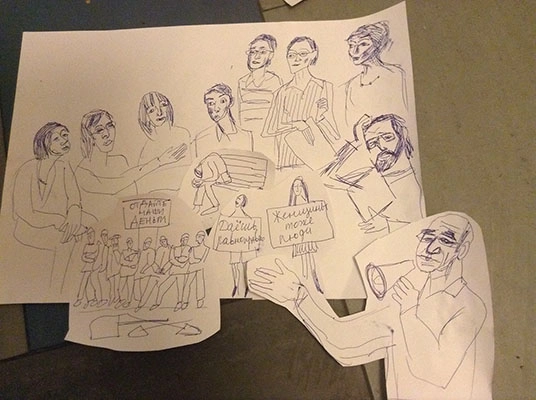

In this atmosphere, the old political divide between servile and critical sociologists has been revived. After the start of the war, social scientists have expressed their positions in open letters of support and protest. Many protesters have had to opt for internal or external exile (hopefully, temporarily).

In March 2022, the media circulated a Rectors’ Union letter of support with 180 signatures. This political gesture seemed to guarantee those universities and their staff a certain degree of security, but made these institutions targets of the cancel culture in the international academic community. Simultaneously, protest letters were signed, individual researchers and independent institutions posted protest statements on their social media sites (Telegram, Facebook, and Instagram channels). The protest letters emphasized the devastating consequences of the war for Russian society and academia (Dubrovsky & Meyer 2022). Soon after the start of the war, Instagram and Facebook were blocked in Russia, and non-restricted social media access became available only through the use of a VPN.

However, most sociologists avoid making any open statements on the invasion. Abstainers explain their choice by considerations of “professional neutrality.” They believe in the neutral rationality of a scholar who should keep cool, provide expertise, and not mess with political issues. This seemingly logical argument is fueled by strong feelings of fear that penetrate the public space.

The atmosphere of public fear has a disempowering and suffocating effect on public sociology. However, certain sociological issues are insistently discussed in both official and alternative public realms.

Criticism of opinion surveys

There is one important topic that has a direct link to traditional public sociology. Oppositional sociologists criticize the methodology of opinion surveys in repressive regimes and during military conflict. They claim that the figures reflecting support for the military operation should not be perceived as an expression of genuine attitudes. Public fear distorts people’s answers; traditional public sociology has become a matter for political manipulation, and its results are mobilized in defense of the war and economic sanctions (Yudin 2022). Such criticism enjoys a consensus among oppositional public intellectuals, while those who express loyalty take opinion poll data at face value.

Strategies of sociologists

When academic freedoms are cut back and public sociology suffers from asphyxia, what are the strategies that sociologists can adopt? The majority of academics continue their traditional business as usual – they do not see any alternative to their work situation. Often they believe that there is still space to perform professional duties and to “keep calm and carry on.” Our colleagues emphasize their educational responsibilities, the importance of helping students to overcome their feelings of embarrassment and disenchantment. Many think that it is time for ethnography and to inspire field research and diaries in different settings of crushing life-worlds. Others turn to the analysis of totalitarianism and dystopias in the classics, which they believe could help to analyze major shifts in the current social reality.

We see that many students and scholars feel “helpless disenchantment” with our discipline. They have realized how dangerous it is to be engaged in public sociology, how huge the costs may be that result from the combination of professional work and civic engagement. Fear, as well as a lack of hope about the prospects of continuing professional work in Russia, cause alienation and (hopefully, temporary) relocation of scholars at risk. There is not enough air for public sociology, its prospects are radically reduced, and protest sociologists are trying to organize an alternative open public space on social media platforms where they can speak openly.

An alternative public realm as a real utopian hope

Protest critical sociologists are trying to make their voices heard in Russia and globally. Their strategy is to continue professional work and to raise their voices in the alternative public sphere made available by new information technologies. Protest journalists work across borders in the online space that grew during COVID-19; they run online public discussions on burning topics concerning life in Russia. Telegram and Facebook channels have created a public sphere for those who protest against the military operation. However, these activities have limited audiences and create an information bubble.

In this alternative public sphere, social scientists discuss foreign affairs as public intellectuals, as well as delving into more abstract conceptualizations of neo-totalitarianism, dictatorship autocracy, colonialism and empire. They are trying to find a proper signifier for the Russian regime. Many feel their responsibility for what happens. They ask themselves: What did we miss? How could we have prevented the war? Why did we fail in our forecasts?

Conclusion

The repression of the public sphere means that public sociology suffers from traumatic asphyxia: a serious pathological condition when a living body can neither breathe nor move due to a lack of access to oxygen. This condition is life-threatening. In the context of the Russian authoritarian regime, possibilities for public sociology have become very limited because of public fear and actual repression. Traditional public sociology suffers under strong censorship and opinion survey results are used as political instruments. But public sociology continues to exist across borders and in the alternative public realm of social media.

The dystopian nightmare that we are living in helps us understand that the sociological tradition we belong to is built on moral commitment, on democratic values that we share steadfastly with others: freedom, reason, equality, solidarity. In the current situation, we have to accumulate professional knowledge which will be available to the public in the future. The present circumstances force Russian sociologists to raise questions about their ambitions and the foundations of their work, and to reflect once more on the strong link between their profession and moral commitment – a reflection which could be avoided before, under the auspices of neutrality.

Svetlana Yaroshenko, St Petersburg Association of Sociologists, Russia <svetayaroshenko@gmail.com>

Elena Zdravomyslova, St Petersburg Association of Sociologists, Russia <zdrav3@yandex.ru>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: