Profitable Bodies and Care Mobilities in Central and Eastern Europe

October 19, 2022

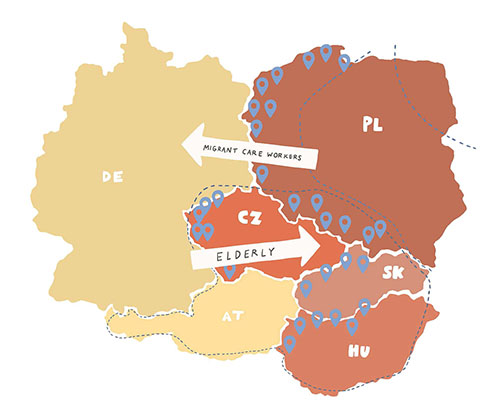

Landscapes of care are rapidly changing in the Visegrad countries (the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Hungary), due to overall marketization of care regimes, outmigration, changes in gender relations, and an increasingly aging population. These developments are leading to new complexities and a diversification of the care sector, consisting of different business actors (including some from the spa and tourism sector), whilst also affecting the role of both the family and the state. Furthermore, care provision is challenged due to gaps created through the outmigration of women into the care markets of richer European countries. Related to this, though involving far fewer people, is the movement of elderly persons in the opposite direction, to countries where care costs are roughly two third less than in more expensive neighboring countries.

In our current research projects “Transnational care landscapes in Central Europe: Privatization, marketization and overlapping mobilities” and “Relocating Care within Europe,” we investigate these two interrelated care mobilities: migrant care workers from Central and Eastern European countries in Germany, and the tiny but emblematic phenomenon of the relocation of German senior citizens to care facilities in Visegrad countries. Both trends can be understood as being complicit in generating profit: extracting labor from “working” bodies (migrant labor) and “entitlements” from frail elderly bodies.

Social reproduction, social citizenship and the body

Despite its centrality in social reproduction and social citizenship, the body is easily overlooked. It is, however, the primary intersection where potentially tension-filled dynamics come together at the smallest scale: the body needs to be nurtured, washed, clothed, and rested. For a worker’s body to be able to work, other bodies must provide services.

Social reproduction is a term developed by Marxist feminists to capture all the invisible work that is needed to repair, maintain, and sustain the daily lives of societies, including social relations and the maintenance of the environments people live in. In a corresponding sense, social citizenship denotes the entitlement to social protection and education that should enable people to become, and remain, healthy and well-educated citizens.

Therefore, social reproduction and social citizenship are closely related. They both take part in the reproduction of the wider systems and infrastructures needed to make “living” and the functioning of a society possible, including care work. When the correlation between the two changes, a problem of social reproduction arises; as occurs when the elderly are moved for care, which can be seen as a relocation of social citizenship. In trying to understand the landscapes of care mobilities in Europe, we use both terms, social reproduction and social citizenship, as analytical tools.

Landscapes of care mobilities in CEE

The outsourcing of care to Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), and the emergence of private care infrastructures, are related to labor migration in various ways through both past and present mobilities. For example, Polish migrant care workers who have worked in Germany are now among the founders of private care homes back in Poland, and they are also sought after as staff because of their work experience and language skills. Recruitment agencies have developed and offer intermediary services for families, connecting them to care homes in the region. Moreover, the elderly in private care homes in the Visegrad countries are often the parents of children who have migrated to work in another country, thereby earning enough to pay for their parents’ care back home. In other cases, the elderly are themselves returned migrants who, after having spent their working lives in Austria or Germany, have earned the right to insurance from these countries and can therefore afford private care. These cases add complexity to the question of social citizenship in European welfare states.

In the Visegrad countries, the emergence of private care facilities seems to be directly related to the care drain caused by outmigration, as illustrated by an example from our research. In a care home located just 2 km from Germany within the Czech Republic, German and Czech senior citizens are cared for together. However, their care is not provided by Czech care workers, because these have left the Czech market for better paid care work in Germany; the jobs are filled, in turn, by migrant care workers from Ukraine and Moldova.

Another case of overlapping mobilities can be seen in the case of Roberto who had suffered a stroke and could no longer live on his own. His children, who could not afford a care home in Germany, moved him to one in Poland which advertised its services for seniors from Germany. Yet Roberto was not originally from Germany: he had moved there from Italy as a young ‘guest worker’, stayed on, had a family, and grew old there. His children, like many other German families, faced the problem of what to do in a care system that relies on obligatory care insurance that needs to be ‘topped up’ by pensions and family funds. In the Polish care home, Roberto tried to use his rudimentary knowledge of German, and Paula, an elderly Polish woman, sometimes translated for him. She grew up in a formerly German area in southwest Poland and spoke both languages. These two elderly people coming together in a private care home in Poland exemplify the complexity of social reproduction and citizenship in today’s Europe. It shows that along with current migration movements, shifting borders and historical displacements after WWII continue to play a role.

Conclusion

Transnational care landscapes in Central Europe extract profits from both bodies that care and bodies that are cared for. We can observe trans-local social reproduction in the region reflected through two interrelated phenomena: (1) the transnationalization of care due to the outmigration of (female) care workers, resulting in a ‘care gap’ in their countries of origin; (2) the, much smaller in scope and scale, reverse phenomenon of care outsourcing through which the elderly are relocated to places where care costs are roughly one-third of those in the home countries. Both phenomena challenge how we conceptualize rights and social reproduction, in terms of European social citizenship and care regimes. We argue that these care mobilities illuminate how the body is involved, but neglected, in the crisis of social reproduction and social citizenship in Europe and its uneven welfare geographies.

Petra Ezzeddine, Charles University Prague, Czech Republic <Petra.Ezzeddine@fhs.cuni.cz>

Kristine Krause, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands <k.krause@uva.nl>