Michael Burawoy was more than a sociologist; he was a builder of sociology – not only through his theoretical contributions, but through the institutions he shaped, the relationships he nurtured, and the global solidarities he forged. He transformed the discipline into a reflexive and practice-oriented field – one that interrogates power, centers the margins, and bridges critique with imagination, theory with action.

In this spirit, I reflect on Michael’s contributions and highlight his enduring impact on the discipline, its methodologies, pedagogies, and global articulations.

Living sociology: embodied practice, reflexive method

Michael’s sociology was not just a theoretical orientation; it was a lived practice, grounded in movement, struggle, and historical consciousness. His final book, Public Sociology: Between Utopia and Anti-Utopia, synthesized decades of reflection on sociology’s dual imperative: to critique existing conditions while cultivating the imagination of alternative futures. Michael gave precise meanings to these contradictory impulses. Utopia, for him, was not a blueprint for a perfect society, but a dialogic and the collective imagining of alternatives, a necessary force that keeps critical thought alive. Without utopia, he cautioned, sociology becomes a mirror of despair. Anti-utopia, in contrast, was the disenchanted but necessary skepticism that tempers naïve optimism. Sociology, for Michael, lived in the tension between these poles – between the desire for transformation and the recognition of what hinders it. In that tension – between what is and what could be – he cultivated sociology as a vocation.

At the heart of Michael’s project was a critique of the discipline itself; a sustained effort to remake sociology from within. He challenged sociology’s Eurocentrism, its closed canons, its reproduction of privilege. Though he stood at the very center of academic prestige, he constantly worked to decenter himself – foregrounding Du Bois, feminist thought, and Global South epistemologies. He inhabited the margins by choice – always reaching outward and downward: into communities, workplaces, and the lives of those experiencing precarity.

In his 2004 ASA presidential address, he famously sketched four types of sociology: professional, policy, critical, and public. These were not separate silos, but a vision for an integrated, dialectical practice. Public sociology, for him, wasn’t the soft wing of the discipline, it was its conscience. He made sociology accountable, insisting that we ask: For whom do we produce knowledge, and toward what end? His call for public sociology was a call to reconfigure the very foundations of what counts as knowledge. As he often said, public sociology is not outreach; it is a conversation that transforms all participants.

This commitment extended to how Michael engaged with movements. He practiced what he theorized. He moved seamlessly between seminar rooms and picket lines, between ISA meetings and the factory floor. From labor union activism in South Africa and Zambia, to the anti-apartheid movement, Occupy Oakland, graduate student organizing, and solidarity with Palestine, Michael’s work blurred the line between the academic and activism.

This transformative vision of sociology was inseparable from his methodological commitments. Central to Michael’s intellectual legacy is the extended case method: a research approach that did not seek to generalize outward, in the usual deductive sense. Instead, it extended from the contradictions observed in everyday life toward an understanding of the broader social structures that shape them. Reflexivity, for Michael, was not confession, it was a theory of knowledge.

This methodological commitment found further expression in one of his most enduring contributions: Global Ethnography, a collaborative project with nine of his graduate students. The book introduced the concept of grounded globalization: a distinctive method for understanding global processes not through abstract models or macro flows, but by tracing how global forces are refracted through specific, localized experiences. Together, these approaches – the extended case method and grounded globalization – reflected Michael’s conviction that theory must be built from below, in dialogue with lived realities, and always attentive to the structural conditions that make knowledge possible.

Teaching sociology, practicing dialogue

For Michael, teaching was not subordinate to research: it was the foundation of a transformative sociology. He frequently rejected the notion that pedagogy was neutral. Teaching, like research, was situated within broader power structures, especially within the neoliberal university. In Laboring in the Extractive University, he diagnosed the university as a site of exploitation, where both students and instructors are often alienated from the process of learning. Yet he also saw in the classroom potential for radical imagination; a space to cultivate sociological inquiry as both critique and care.

He often said: “Our first public is our students.” In his eyes, each student was a story worth hearing, a challenge worth exploring. He created a space where learning was collective, where ideas were debated fiercely yet generously, and where knowledge was never hoarded but shared. As his student, I came to see that Michael’s greatest gift was building a community where we could recognize and cultivate each other’s insight and potential. He treated our personal struggles not as distractions, but as entry points into theoretical analysis.

He modeled an ethics of solidarity in the classroom; regularly crediting students in his publications, recognizing the labor of teaching assistants, and mentoring them as intellectuals, not aides.

He was, without doubt, one of the most beloved teachers of his generation. But more importantly, he redefined what teaching could be and taught some of his most memorable lessons in the street: in teach-ins at Sproul Plaza at the University of California, Berkeley, and on picket lines. For him, pedagogy and teaching were inseparable from political commitment and collective struggle.

As for many of us, his mentees, Michael Burawoy did not create a school of thought. He created a community of practice; one defined not by discipleship, but by disagreement. He didn’t want to be followed. He wanted to be argued with. We do not all follow a particular theoretical paradigm – not even Marxism, which so deeply shaped his own work. What unites us is not methodological conformity or ideological alignment, but a common orientation to the world: a belief in the urgency of sociological thinking, and its capacity to illuminate – and reshape – the conditions of our lives. His sociology was deeply embedded in, responsive to, and accountable for the political and ethical challenges of its time, and so is ours.

Michael’s commitment to pedagogy as labor was directly linked to his commitment to global sociology.

Global sociology: from solidarity to structure

For Michael, the ISA was not merely an administrative platform but a laboratory for realizing his vision of global sociology. He rejected the idea that simply expanding global participation – through conferences, collaborations, or citations – was sufficient. Instead, he called for a deeper transformation of the discipline’s epistemic structures. Drawing on broader debates about “provincializing Europe,” Michael has argued that sociology must confront its Northern biases and redistribute intellectual authority. Internationalization, for him, was not about inclusion into a dominant model, but about cultivating a dialogical, polycentric sociology rooted in mutual recognition and the vitality of national traditions.

Michael called for a shift from the vertical integration of knowledge, where theory is produced in the Global North and data collected in the Global South, to a horizontal structure of exchange, where theoretical and empirical contributions emerge from all parts of the world. Global sociology, for Michael, was not the study of the global; it was the globalization of sociology as a discipline: connecting voices, redistributing authority, and enabling a more just and inclusive production of knowledge. His vision of global sociology was not extractive. Instead, he emphasized reciprocity. One might say that, for him, globalizing sociology required globalizing its very conditions of production.

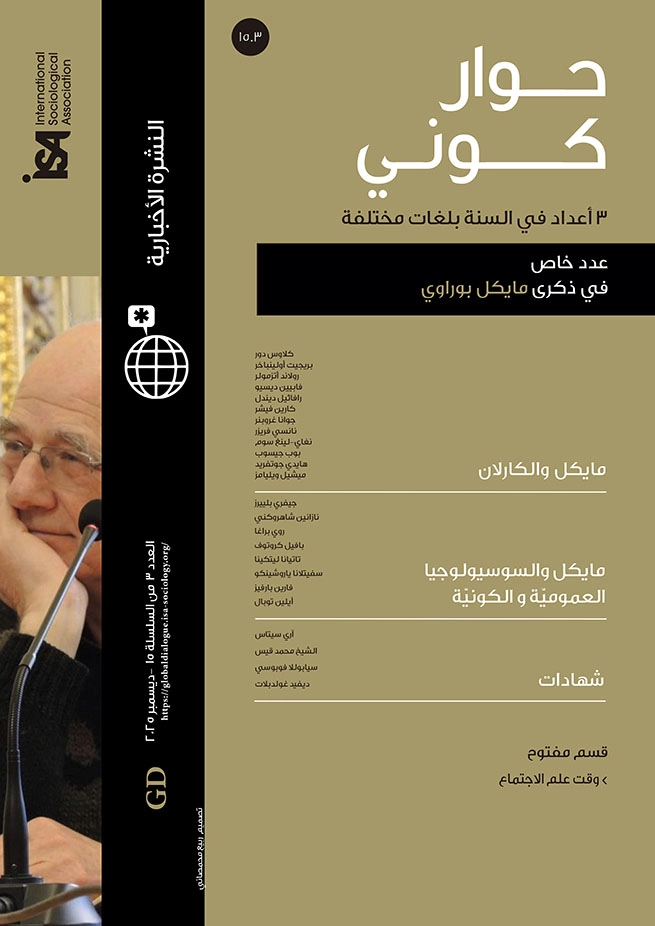

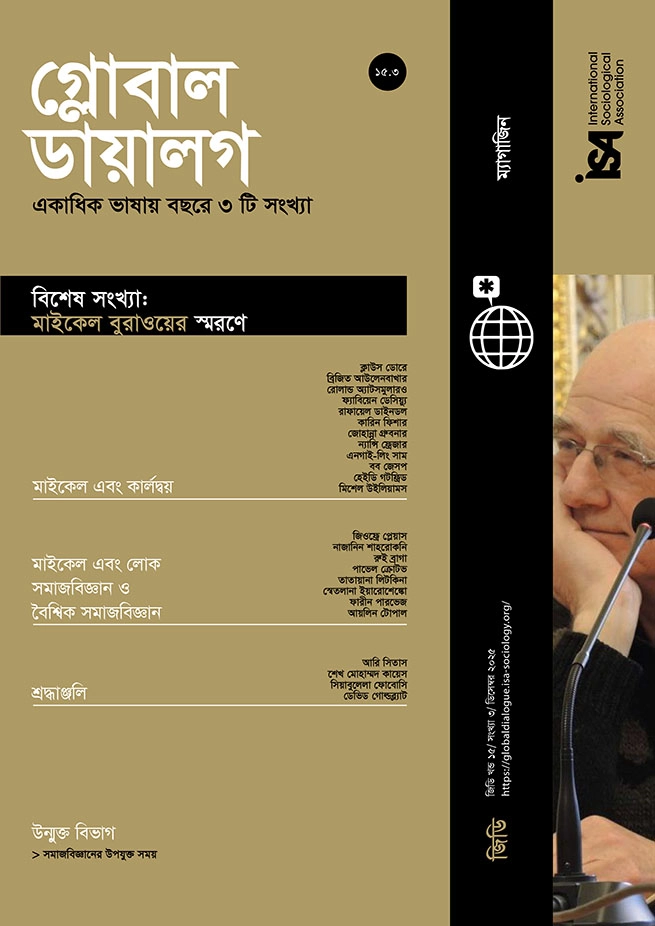

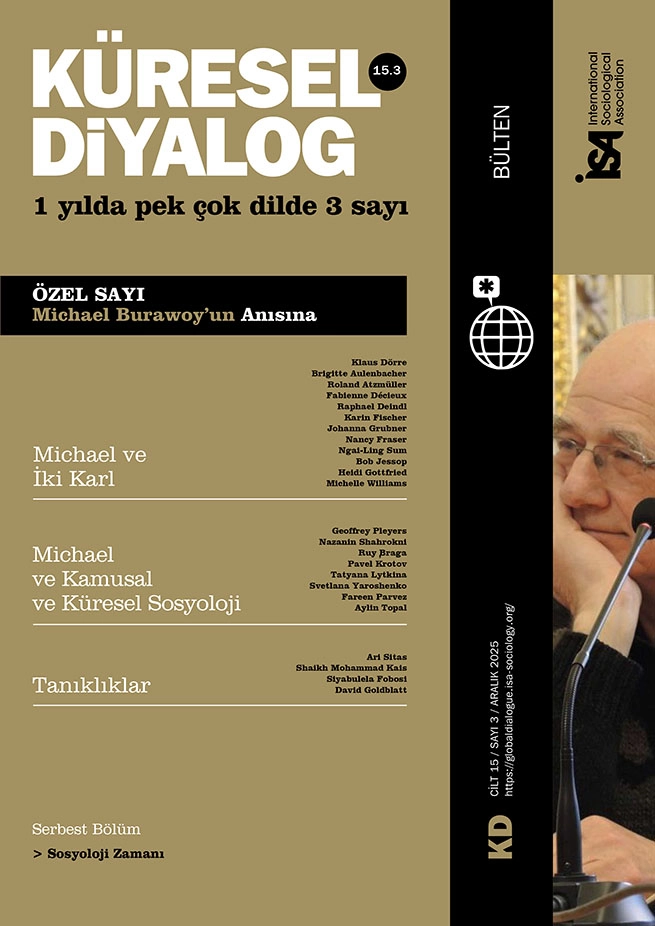

Under his leadership, Global Dialogue was launched as a multilingual magazine that would circulate sociological debates across linguistic and geopolitical boundaries. Translated into 15 languages, it embodies his insistence on multilingual, multivocal, polycentric sociology. He knew that translation is not merely technical, it is political. He supported initiatives to expand the ISA’s regional reach, democratize its structures, and support scholars in politically or economically precarious environments.

His 2008 visit to Iran, where I had the privilege of accompanying him, captured this ethos. He refused to let visa regimes, sanctions, or state repression – and borders, whether political, linguistic, or disciplinary – determine whom he engaged with. When Iranian sociology was isolated by international sanctions and domestic repression, Michael insisted: “If they can’t come to us, we must go to them.” And he did, determined to ensure that Iranian sociologists remained part of the global conversation. Where others saw a pariah state, he saw an intellectual community. His thirst for seeing, listening, and learning – and his gift for making all those around him feel seen, heard, and validated – left an indelible mark among his Iranian colleagues.

In Iran, Michael’s role as an empathetic interlocutor coexisted with the unrelenting pull of the consummate ethnographer within him. Instead of confining himself to Tehran’s comfortable enclaves, he ventured beyond the sanitized experience of the capital, riding buses in and between Iran’s smaller towns. “How else would you connect to people?” he challenged us. We laughed as we reminded him, “Michael, you don’t speak a word of Farsi!” Yet language proved to be no barrier. Michael had an uncanny ability to inhabit spaces, to absorb and reflect the textures of local life. He was never a distant observer; he was a participant in the unfolding stories of those around him. Whether chatting with a bus driver, haggling with a vendor, or exchanging ideas with university professors, he broke through every wall with his genuine curiosity and that trademark humor, forging connections that transcended words. He taught us that the ethnographic encounter was not about language mastery, but about human curiosity and dignity.

When asked what message he had for Presidents Ahmadinejad and Bush, Michael replied: “Make it mandatory for presidents to take Sociology 101.” In today’s climate, where political leaders increasingly defund and delegitimize the social sciences, his quip reads less as a joke and more as a prescient critique of the estrangement between power and critical knowledge.

In the aftermath of Michael’s visit, the Iranian Sociological Association established a dedicated section on Public Sociology, now one of its most vibrant and active branches. I had the privilege of translating his call for public sociology and helping introduce the concept to the Farsi-speaking academic community. His work resonated deeply: numerous books and symposia on public sociology have since been organized, and key texts, including Michael’s essays and interviews, were translated; Iranian sociologists embraced his vision of engaged, critical scholarship; and upon his passing, the Association held a special commemorative event in his honor. National newspapers reported on his legacy, underscoring the enduring impact of his visit and ideas on Iran’s sociological landscape.

For Michael, global sociology was a practice – of listening across borders, of translating across difference, and of insisting that knowledge is never truly global unless it is shared, struggled over, and spoken in many tongues.

Carrying the project forward

In today’s landscape of deepening inequality, rising authoritarianism, climate breakdown, and global displacement, Michael’s insistence on a public, critical, and hopeful sociology is more urgent than ever. He taught us that sociology must respond to the conditions of its time, and that it thrives in moments of crisis; not despite them, but because of them.

To carry forward his legacy means sustaining the values he exemplified:

- critical inquiry rooted in dialogue and humility;

- teaching as a site of mutual transformation;

- research that engages publics across divides;

- a refusal to separate analysis from responsibility.

And perhaps that is the legacy he leaves us with at the ISA: not just a set of concepts or typologies, but a way of doing sociology that is at once critical, dialogical, and deeply committed to the world it seeks to understand.

Nazanin Shahrokni, Simon Fraser University, Canada <nazanin_shahrokni@sfu.ca>