Jan Szczepański – Building a Precarious Bridge

May 16, 2014

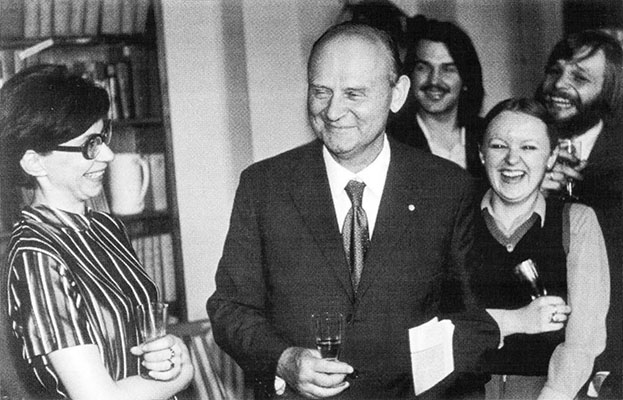

Jan Szczepański (1913-2004) was a Polish sociologist, who served as President of ISA from 1966 to 1970. He was the first person from the Eastern bloc to occupy this position. His publications appeared in many editions in Poland. His newspaper columns were also highly appreciated and widely discussed. He was not indifferent to public issues, and participated actively in political life, being a Member of the Parliament of the People’s Republic of Poland (1957-61, 1972-85) and a Member of the Council of State (1977-82). As ISA President at the end of the 1960s he faced two major challenges. Firstly, dialogue between East and West as well as with the Global South which resulted in organizing the Congress of ISA in Eastern Europe (Varna, Bulgaria). Secondly, according to his diary, as President he was weighed down by tedious paperwork when trying to settle even the simplest organizational matters.

The specificity of the Polish political situation in the communist era, as noted by sociologist Vinicius Narojek, consisted in the limited legitimacy of the state. On the one hand, the communist regime was recognized by the majority of the population, especially in the initial period, as an external force imposed from above by the Soviet Union and, thus, contrary to traditional national values. On the other hand, representatives of the authorities themselves were often seen as a necessary evil, acceptable insofar as they were able to distance themselves from their Eastern Protector. One of the pillars of legitimacy was the ability and willingness of those in power to circumvent the implementation of the orthodox Soviet doctrine. The “People’s Democracy,” especially in times of crises (1956, 1970, 1980), was both strong and weak, controlling and seductive.

The Polish intelligentsia adopted widely different attitudes toward this situation: from total opposition to devoted and enthusiastic contributions to the system. Many people took difficult, and morally uncomfortable intermediate positions. That was where we can find Jan Szczepański, who, after 1956, participated in the creation of a new political line within the Communist Party while, at the same time, he remained critical of the many abuses and distortions perpetrated by the communist system. Thanks to the efforts of such people, forming a shaky bridge between absolutist power and intellectual elites, it became possible for the Polish intelligentsia to hold on to a certain relative autonomy. In assuming a certain freedom of action, the intelligentsia played a significant role in the creation of the later oppositional structures of the “Solidarity” movement. In most countries of the Soviet bloc sociology departments were not present in the university, because Institutes of Marxism-Leninism had a monopoly of the interpretation of social life. In this regard the revival of the social sciences in Poland after the death of Stalin was unusual in the Soviet Bloc, giving birth to Polish sociologists who were also great public intellectuals such as Jan Szczpański, Maria Ossowska and Stanisław Ossowski, Zygmunt Bauman, Maria Hirszowicz and Stefan Nowak – all famous and familiar figures.

The unique position that Szczpański was able to forge in these difficult circumstances – an independent sociologist, advising an authoritarian government in matters of education and social policy – gave him the opportunity to practice public sociology in this gloomy period. He saw himself not as a detached academic, but as a researcher highly concerned with current social problems, and promoting possible solutions. Due to his influence in political life, Szczepański made it possible for many important Polish scientists to travel abroad. He also fought for the allocation of printing paper to public institutions so that many sociologists and other intellectuals could publish their books. He was even involved in social protests, something very rare in the Stalinist era, requiring great courage. For example, in 1954, he was one of 34 intellectuals who signed a letter protesting against censorship, although, after the first arrests, he withdrew his support.

He was a widely read journalist and columnist. His political position gave him the possibility of limited criticism of authority. The public he reached with his popular writings gave him influence over the minds and attitudes of an entire generation of Poles. In this way he introduced some basic concepts of sociology into public discourse, creating space for a modicum of public debate in an era when freedom of speech was precarious. However, this mode of practicing sociology has meant that today – ten years after his death – Szczepański is all but forgotten in Poland. Despite his hundreds of publications focusing on current problems, he did not leave behind any timeless theory or impressive school of thought. On the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his birth, a series of events and conferences were organized by the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Polish Sociological Association. However, his name does not resonate with contemporary students of the social sciences.

The life of Jan Szczepański was a constant struggle to improve the fate of people – an attempt to fulfill the promise of “socialism with a human face.” His balancing act proves that even in an extremely undemocratic system, a space for public sociology can be found. However, such a possibility came at a price: trapped into a series of indoor games and having to make uncomfortable compromises.

Adam Müller, Kamil Lipiński, Mikołaj Mierzejewski, Krzysztof Gubański, Karolina Mikołajewska, the Public Sociology Lab, University of Warsaw, Poland