Read more about Tracking Inequality

Falling Inequality in Latin America

by Juliana Martínez Franzoni and Diego Sánchez-Ancochea

October 25, 2013

Globalization has brought not just greater inequalities but also chronic economic uncertainty to the world’s population. Governments have failed to effectively develop or adapt social protection systems to reduce economic insecurity. They have turned to means-testing, behavior-testing, selectivity, targeting, conditionality, and workfare. Emancipatory universalism has been sacrificed everywhere.

In that context, there has been renewed interest in universal unconditional basic income grants, namely cash transfers given to all citizens to ensure that they have a minimal income. While conditional cash transfers have become popular all over the world, the unconditional universal alternative has not been adequately considered. I joined SEWA (Self-Employed Women’s Association) in a project funded by UNICEF to launch pilot studies of the effectiveness of such universal income grants in India.

In India, public debate on cash benefits has been contentious. On one side are advocates of food subsidies, wishing to extend the Public Distribution System to 68% of the population, as planned in the National Food Security Bill, now before parliament. Critics believe it will worsen corruption, cost a vast amount, provide low-quality food and be unsustainable. On the other side, advocates of cash transfers have been accused of wanting to dismantle public services and cut social spending. The real problem is that existing policies have left over 350 million people, about 30% of the population, mired in poverty, even after two decades of high economic growth.

In that context, in 2011 we launched two pilots to test the impact of basic income grants, funded by UNICEF, with SEWA as coordinator. Results were presented at a conference in Delhi on May 30-31 (2013), attended by the Deputy Chair of the Planning Commission and the Minister for Rural Development, who is in charge of cash transfer policies. A private presentation was later made to Sonia Gandhi, at her request.

In eight villages in Madhya Pradesh, every man, woman, and child was provided with a monthly payment of, initially, 200 rupees for each adult and 100 rupees for each child paid to the mother or guardian; these were later raised to 300 and 150 respectively. We also operated a similar scheme in a tribal village, where for 12 months every adult was paid 300 rupees a month, every child 150. Another tribal village was used as a comparison.

The money was paid individually, initially as cash and after three months into bank or cooperative accounts. National and state authorities learned the lessons they must follow if they are to roll out direct cash benefits across this vast country.

In the pilots, villagers were not allowed to substitute food subsidies for cash grants. No conditions were imposed on recipients. This we regard as crucial. Those who favor conditionality say in effect they do not trust people to do what is in their best interest and that the policymaker knows what is.

The designers of the pilots believe basic income grants will work optimally with good public services and social investment, and that they would operate better if implemented through a Voice organization, i.e., a body giving members the capacity to act in unison. This has been my position on basic income for many years, i.e., that it will only work optimally if the vulnerable have institutional representation. So, as a test of this claim, in half the villages selected, SEWA was operating, while in the other half it was not.

Critics claim that cash benefits would be wasteful and inflationary, and would lower growth, by reducing the labor supply. Advocates believe they have the potential to unlock constraints to improved living standards and community-based economic development.

Starting with a baseline census that collected data on many demographic, social, and economic characteristics, and then an interim and final evaluation survey covering the same aspects, we studied the impact of the basic income grants over eighteen months, using randomized control trials (RCT) that compared the results in households and villages receiving basic incomes with the results in twelve other “control” villages where nobody received the basic incomes. In addition, over 80 detailed case studies giving individual and family accounts of experiences were conducted by an independent team.

We have much more analysis to do, but as the conference showed the story is fairly clear. Before mentioning a few findings, note that contrary to some assertions, a majority did not prefer subsidies (covering rice, wheat, kerosene and sugar), and as a result of the experience of basic incomes more came to prefer cash to subsidies. Eleven results stand out.

1. Many used money to improve their housing, latrines, walls and roofs, and to take precautions against malaria.

2. Nutrition was improved, particularly in scheduled caste (SC) and scheduled tribe (ST) households. Perhaps the most important finding was the significant improvement in the average weight-for-age of young children (World Health Organization z-score), and more so among girls.

3. There was a shift from ration shops to markets, made possible by increased financial liquidity. This improved diets, with more fresh vegetables and fruit, rather than the narrow staple of stale subsidized grains, often mixed with stones in the bags acquired through the shops of the Public Distribution System (PDS), the government-regulated food security system. Better diets helped to account for improved health and energy of children, linked to a reduced incidence of seasonal illness and more regular taking of medicines, as well as greater use of private healthcare. Public services must improve!

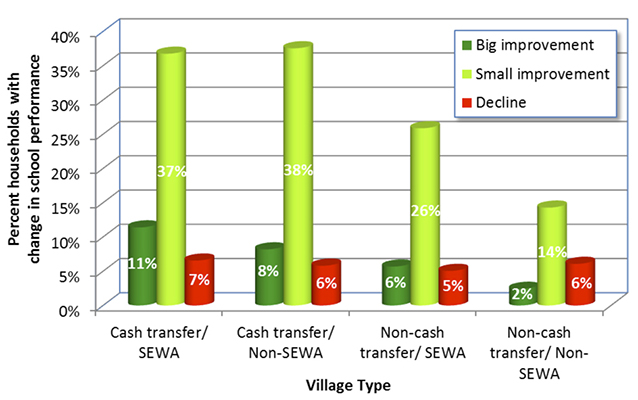

4. Better health helped to explain the improved school attendance and performance (figure 1), which was also the result of families being able to buy things like shoes and pay for transport to school. It is important that families were taking action themselves. There was no need for expensive conditionality. People treated as adults learn to be adults; people treated as children remain childlike. No conditionality is morally acceptable unless you would willingly have it applied to yourself.

5. The scheme had positive equity outcomes. In most respects, there was a bigger positive effect for disadvantaged groups – lower-caste families, women, and those with disabilities. Suddenly, they had their own money, which gave them a stronger bargaining position in the household. Empowering the disabled is a sadly neglected aspect of social policy.

6. The basic income grants led to small-scale investments – more and better seeds, sewing machines, establishment of little shops, repairs to equipment, and so on. This was associated with more production, and thus higher incomes. The positive effect on production and growth means that the elasticity of supply would offset inflationary pressure due to any increased demand for basic food and goods. It was encouraging to see the revival of local strains of grain that had been wiped out by the PDS.

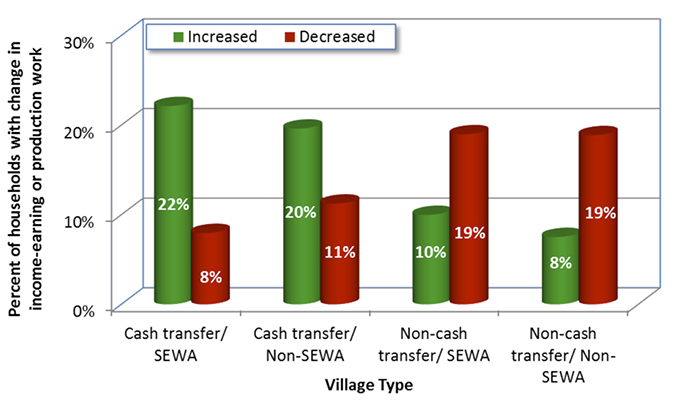

7. Contrary to the skeptics, the grants led to more labor and work (figure 2). But the story is nuanced. There was a shift from casual wage labor to more own-account (self-employed) farming and business activity, with less distress-driven out-migration. Women gained more than men.

8. There was an unanticipated reduction in bonded labor (naukar, gwala). This has huge positive implications for local development and equity.

9. Those with basic income were more likely to reduce debt and less likely to go into greater debt. One reason was that they had less need to borrow for short-term purposes, at exorbitant interest rates of 5% a month. Indeed, the only locals to complain about the pilots were moneylenders.

10. One cannot overestimate the importance of financial liquidity in low-income communities. Money is a scarce and monopolized commodity, giving moneylenders and officials enormous power. Bypassing them can help combat corruption. Even though families were desperately poor, many managed to put money aside, and thus avoid going into deeper debt when financial crises hit due to illness or bereavements.

11. The policy has transformative potential for both families and village communities. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Unlike food subsidy schemes that lock economic and power structures in place, entrenching corrupt dispensers of BPL (Below Poverty Line) cards, rations, and the numerous government schemes that supposedly exist, basic income grants gave villagers more control of their lives, and had beneficial equity and growth effects.

A claim we have made in the public debate in India is that universal schemes can be less costly than targeted schemes. Targeting, whether by the discredited BPL card or by other methods, is expensive to design and implement. All targeting methods have high exclusion errors – evaluation surveys showed that only a minority of the poorest had BPL cards.

In sum, basic income grants could be a vital part of a 21st-century social protection system. These are momentous times in Indian social policy. Old-style paternalism must be rejected and a new progressive system constructed.

Guy Standing, School of Oriental and African Studies, UK

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: