Read more about Tracking Inequality

India’s Experiment in Basic Income Grants

by Guy Standing

October 25, 2013

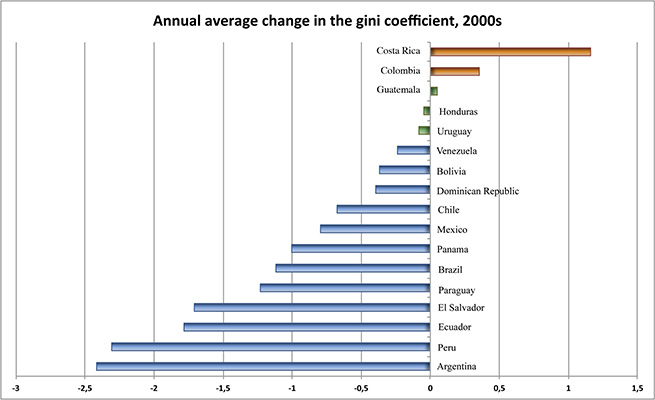

Latin America has traditionally been the most unequal region of the world and has suffered from the negative consequences of inequality: dysfunctional politics, powerful elites, social tensions and difficulties to reduce poverty. During the past decade, however, for the first time since inequality statistics are available, the region as a whole and twelve out of eighteen countries have witnessed a drop in income inequality.

What accounts for this unprecedented change? There was the so-called “left-turn” in the political landscape: following democratic transitions mostly led by conservative governments, all across the region, progressive parties took over the executive power and gained majorities in the legislative in the early 2000s. There is little doubt that left-wing governments from Venezuela to Chile have placed distribution at the heart of their policy agenda, but inequality has also gone down under conservative administrations in countries like Colombia and Mexico. Across the board, there were policy changes reflecting the widespread disappointment with neoliberal ideas and their unmet promise that markets would create formal jobs and resources for (mostly anti-poverty) social policy.

Most new governments benefited from positive external conditions. With China buying lots of resources to fund its manufacturing miracle, the international price of commodities like gas, oil, soy and meat underwent an extraordinary increase and Latin American exports grew rapidly. Between 2000 and 2009, Latin American exports to China increased seven-fold, augmenting dollars available to fund new social programs.

The combination of fiscal resources and parties that believe in an active role of the state for distribution led to positive changes in labor and social policy. Formal employment increased along with average and minimum wages, and coverage in social programs expanded. Between 2008 and 2012 South America even succeeded in protecting formal jobs and social spending in the midst of one of the worst global crisis experimented in the last century. Over 100 million people were reached with monetary transfers through programs that link cash and access to basic social services – namely conditional cash transfer programs.

Of course, performance has not been the same across countries. Some have been more successful than others in promoting positive change not just in terms of social investment but of massive job creation and formalization of labor arrangements. In Brazil, the result of the effort to formalize jobs and increase minimum wages has been spectacular: between 2002 and 2012 the number of Brazilians in the middle class increased from 69 million (38 percentage of the total) to 104 million (53 per cent). Uruguay has become the only country in Latin America that uses collective bargaining successfully to benefit large segments of the population. Other countries have done very well in terms of expansionary social policies yet not so well in terms of improving labor conditions overall. Interestingly enough, this mixed performance is found in countries led by what some people call “good”, fiscally responsibly left (as in Chile), as well as those with a “bad”, “populist” left like Bolivia.

Recent improvements have led some to talk about a new era and offer Latin America as a showcase for the rest of the world – when inequality continues to grow from Madrid to Beijing. Yet we should be careful about excessive optimism and recognize significant shortcomings of Latin America’s recent path.

First, the massive gains of the 2000s in labor and social incorporation did not fully reach Central America, home to over 80 million people: countries north of Panama continued to rely on exporting their labor force, mostly to the United States and inequality only decreased significantly in El Salvador (and even there the reliability of data is in serious doubt due to constraints in accessing the very rich and the very poor in violent communities). Central American countries are struggling to increase government revenues, reduce the influence of the elite and, at the same time, develop good jobs and high-quality social services.

Secondly, in the region as a whole, the wealthy continue to control a majority of the resources and are failing to pay their fair share of taxes. With a few exceptions tied to the proceeds from oil and gas extraction in Bolivia and Argentina, distribution has taken place without touching corporate profits. Built largely around family ties, Latin American firms continue to be as stingy as before. In Brazil, the very rich have supposedly lost comparatively in the last years, but high-level executives in São Paulo earn an average of 600,000 dollars per year – more than in New York or London.

Last and very critically, there is a common lack of progress in the transformations of the economy. Same as a century ago, Latin America still sells raw material in exchange for manufactured goods with higher value added. This is particularly worrisome not only because it slows down the creation of formal employment and it makes progress dependent on China but also because this extractive economy poses a threat for the future of the planet.

Juliana Martínez Franzoni, University of Costa Rica, ISA Member of Research Committee on Poverty, Social Welfare and Social Policy (RC19)

Diego Sánchez-Ancochea, University of Oxford, UK

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: